CHAPTER SEVEN - Christmas, 1941

During the days before Christmas, Mother followed her annual tradition of baking Scotch oatcakes and shortbread. She did this every year; it was her special gift to her sister Henrietta, and her two brothers, Charlie and Billy, and their families. Uncle Billy’s wife Maude was so crippled by rheumatoid arthritis that she was unable to bake, and Uncle Charlie’s wife Agnes was bedridden as a result of a stroke.

Mother also put up the Christmas tree, bought gifts, and played Christmas carols on the piano. She wanted to make Christmas bright and happy for all of us, but it was a time of great anxiety. She listened regularly to the CBC radio newscasts that came on first thing in the morning, again at noon and at suppertime, and late in the evening. The last thing she did every night before going to bed was tune in to the news. The radio so dominated our lives that one day Barbara announced, ‘When this war’s over, I’m never going to listen to the news again!’

For almost three weeks, the Canadian troops in Hong Kong fought a losing battle against insurmountable odds. Although our men fought valiantly, there were only 1,000 of them, and they were under-trained. They were certainly no match for the 60,000-strong Japanese army that had become battle-hardened during ten years of fighting against China. After three weeks of combat, lacking food, water and ammunition, the Canadians had nothing left to give; on Christmas Day, they were finally forced to surrender.

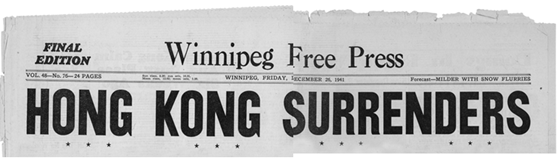

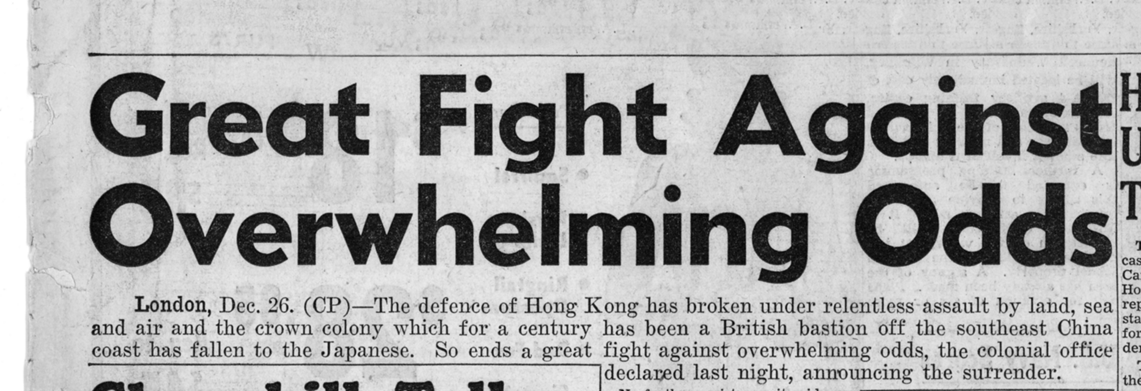

The following day, the Free Press and The Winnipeg Tribune proclaimed the news.

The Grenadiers, in spite of their defeat, were proclaimed heroes. The Free Press printed many platitudes penned by the pundits of the day.

‘The news that fighting has ceased in Hong Kong marks the end of one of the most gallant episodes in the history of Canadian arms,’ said Defense Minister J.L. Ralston.

Lieutenant Colonel J. N. Siemens, commander of the Second Battalion of the Grenadiers, paid tribute to the men of the first battalion with these words: ‘While we deeply regret the inevitable loss that is sure to follow in the wake of the surrender of Hong Kong, we are justly proud of the gallant stand made by the men of the Winnipeg Grenadiers and their sister regiment from Quebec. They have added a glorious page to the annals of Canadian heroism.’

And from the elderly Lieutenant-Colonel J. B. Mitchell, who had commanded the regiment until his retirement in 1920, came these words: ‘I always knew that the Winnipeg Grenadiers had the stamina of good old Anglo-Saxon stock to hold out in the face of great difficulty.’

Headlines from the Winnipeg Free Press, Friday, December 26

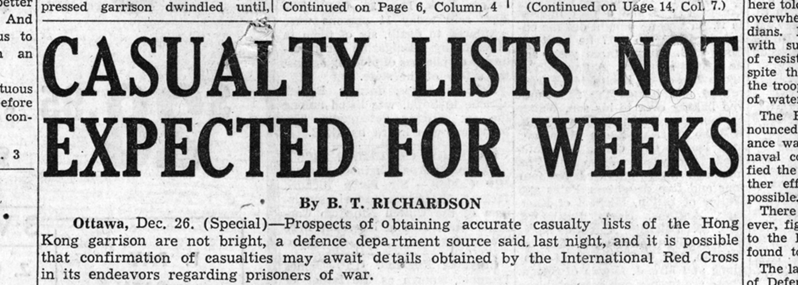

The families of the Grenadiers wanted only to receive word of the men’s safety, but the Free Press warned that it might take weeks to obtain casualty lists through the International Red Cross. Mother had only the newspapers as a source of information. Although she didn’t hear directly from Daddy, she faithfully wrote regular letters, telling him all the family news. Her first letter after the fall of Hong Kong was full of details about our first Christmas without him. Before he left he had given her money to buy gifts.

My Dearest One,

I hardly know what to say to you after this terrible time of trial and suspense, but I want you to know that God will bring you back to us one day. I ask nothing more of this life than to have you home again to help raise this lovely family with me. I know only too well what you must have felt, and I have prayed constantly that you be given strength and courage and patience to live through the days until we meet again.

I tried to make Christmas as bright as possible for the children, and our friends were all so kind to us. We had several invitations to dinner. I would have to see you to tell you all the lovely things people did to help us.

Your present to me was a lovely gold-filled locket and chain, and I wear it with your picture in it. The picture is one of you smiling at me in a canoe on the river, and I put one of myself in the other side. I wear it always, dear, even in bed. I only take it off when I wash myself. If I am wearing a dress that doesn’t suit it, I just slip it inside. It is my lucky charm. Roger is so cute — he is always wanting to open my locket, and he kisses our pictures, saying ‘I love you, Daddy. I love you, Mummy.’ I didn’t tell him to do it, either!

I gave the girls beautiful dolls, and Roger a big delivery truck from Daddy. Honestly, dear, they talk of you constantly, and when Roger can’t do exactly as he pleases, he says ‘My Daddy told me to!’ He is always kissing your picture and telling everybody about you. Barbara’s prayers for you are most touching, and Margaret’s too.

When Daddy received this letter, he wrote back, sounding sad and lonely.

Lucy Darling,

Have just received your letter and it’s lovely to get news of so many friends, but especially of yourself and our three dear children.

Am still keeping fit and am studying bridge to help pass the time.

Your letter made me quite homesick and longing for the time when we can be reunited. I’m very glad everyone is so kind to you. It relieves my anxiety considerably. I DO wish I could see you all again. Please God it won’t be long.

Look after the children and yourself for me.

Ever your loving

Vic

(F. V. Dennis)

Mother also received a moving letter from our grandfather in England, a letter that did a great deal to lift her spirits, though she wept when she read it.

My Dear Lucy,

My very dear and brave little daughter — I can’t express how much I admire the wonderful courage you have shown.

I have wanted to write to you for some time, but have not known how or where to find the words which will convey what we all feel for you in this time of dreadful trial and suspense.

We too are very worried and are hoping against hope that the absence of bad news so far, means that good news will be forthcoming in time. But we also realize how much more difficult it is for you to keep a brave heart and a cheerful countenance with the dear children always in your mind, and with their childish prattle about their dear Daddy.

I am waiting for good news. Of course, I have nothing to go on except the fact that as a family we have always been fortunate. We all came safely through the last war, and so far have suffered no personal damage in this one, and I won’t think that we are going to be less fortunate now. It must take some time for the lists to come from Hong Kong, and until they do, I am thinking of Victor as a prisoner of war who is concerned about his wife and little ones, as his wife is about him, and who is hoping that this wretched war will soon be over so that he may be restored to his family.

Kiss the dear children for Grandad with all my fondest love to them and to your own dear self, and God bless and keep you all.

From your everloving Dad,

F. A. Dennis

On the home front, the people of Winnipeg celebrated the Christmas season as usual, visiting friends, going to parties, skating and tobogganing. On New Year’s Eve, the Capitol and Metropolitan Theatres ran double features, the Puffin Ski Club held a ball in the Royal Alexandra Hotel, and many people held private parties. Mother had been invited out to dinner, but decided to stay home with us instead. She lit the fireplace, and we played Snakes and Ladders, and Checkers, and we drank hot cocoa with marshmallows on top before being tucked into bed well before midnight.

I didn’t feel like sleeping. I knelt on my bed and leaned my elbows on the windowsill, pressing my forehead against the frosty glass and gazing down on the quiet, snow-covered street. Our street looks just like the picture of the little town of Bethlehem in our Christmas carol book, I thought. The lights shone out from the neighbouring houses, and the smoke from the chimneys curled into the wintry sky. My new Christmas pajamas, pink flannelette covered with playful white kittens, hugged my little girl’s body as I remembered the Christmas just past. Even without Daddy, it had been a happy time. On Christmas morning, Mother had run downstairs before us to turn on the tree lights, just as Daddy always did, and Santa had come in the night and filled all the stockings and eaten the milk and cookies we had left for him.

There was a huge truck for Roger, and life-sized baby dolls for Barbara and me. Mother said these gifts were from Daddy.

We thought he’d sent them from Hong Kong, but we later learned that he’d given Mother money to buy them before he went away. Barbara named her doll Mary, and I called mine Marion, after my pretty teen-aged cousin in Medicine Hat. We also got gifts from Santa. Mine was a grown-up dresser set with a brush, comb and mirror, Roger’s was a set of toy soldiers, and Barbara was thrilled with hers — a wooden rocking cradle with a music box inside that played Rock-a-bye Baby.

‘It’s just like a real baby cradle,’ she said. ‘I’m going to take special care of it so I can show it to Daddy when he comes home.’

Unfortunately, a few days later she dropped the cradle while carrying it down the stairs, and the music box would no longer play its lullaby. But as soon as Mr. Brown heard about this mishap, he came to the rescue. ‘All our friends are so kind to us,’ Mother wrote to Daddy.

Harold Brown came all the way over here from River Heights on Sunday, just to fix Barbara’s cradle. She accidentally dropped it down the stairs, and the music box wouldn’t play any more, so Harold took it apart and fixed it for her.

She was so tickled, because she wants to keep it nice to show to you.

Before Christmas, Mother had sewn matching velvet dresses for us girls, with white lace at the collar and cuffs. Mine was forest green and Barbara’s was royal blue.

‘I’m a princess and you’re just a tree,’ said Barbara.

‘Hush!’ said Mother. ‘You both look lovely.’

She also made a little suit for Roger with navy blue velvet short pants and a white cotton shirt with a blue velvet bow tie.

‘He looks such a little gentleman,’ everyone said. ‘Just like his Daddy.’

All the aunts, uncles and cousins had come for Christmas dinner. Mother had cooked a huge turkey stuffed with Scotch oatmeal and onions. There was gravy, mashed potatoes, turnips, and canned green peas. Cousin Jimmie sat beside me and spooned cranberry sauce onto my plate. He told me it was really good, but I didn’t like the taste of it, and it turned my potatoes pink. I started to cry, and Mother took my plate out to the kitchen and scraped the pink potatoes into the garbage. She was cross with Jimmie.

‘It’s a waste of food,’ she said, but Jimmie just laughed.

There were parties to go to, both before and after Christmas.

Mr. Brown belonged to the Kiwanis Club, and he took the three of us, along with his two children, Douglas and Valerie, to the annual Kinsmen’s Club Children’s’ Christmas party in the Marlborough Hotel downtown. The party was held in the elegant red and gold ballroom on the top floor of the hotel. The room was all decorated for Christmas with a huge tree, and tinsel hung from the chandeliers and big red bows were stuck to the walls. We had hot dogs and ice cream and cookies and chocolate milk, and Santa Claus appeared on the balcony above the ballroom in his red suit and white-bearded chubbiness and jingled his bells and waved to us before descending to the stage where he proceeded to dole out gifts to every child. I got a painting set and Barbara a sewing kit and Roger a colouring book and crayons. We also got bags of those shiny, hard Christmas candies that burnt our tongues when we sucked on them.

Between Christmas and New Year’s the Second Battalion of the Grenadiers held a party for the children of the men of the First Battalion.

So many people came to our house to visit, bringing flowers and bottles of sherry for Mother, and candy canes and Christmas oranges for us. Guests would arrive, their faces ruddy and their noses dripping from the cold. Struggling to latch the heavy storm door, they’d let gusts of frigid air into the front hall. Once inside, they’d remove their snowy boots, stamping and laughing, and then they’d carry their fresh-smelling fur coats and hats up to Mother’s bedroom where they’d lay them across her bed. They’d blow their noses into freshly ironed linen handkerchiefs and run their fingers through their hat-mussed hair. We children would follow them every step of the way, giggling and chattering.

Mother would make tea, and bring out oatcakes and cheese and shortbread and fruitcake, and we’d get to stay up late.

After everyone had gone home, Mother would turn off all the lights in the living room except the ones on the Christmas tree. We had a special string of Mickey Mouse lights. Every bulb had a little glass shade with a picture of Mickey or Minnie Mouse, Pluto, Goofy or Donald or Daisy Duck. We’d sit in the soft glow, singing carols. I loved it when we sang Silent Night. I’d imagine snow gently falling around the manger where the baby Jesus lay sleeping, and angels singing in the bright sky overhead.

Now it was all over. Mother would take down the Christmas tree and put away all the decorations, and I’d go back to school.

A train whistled hauntingly in the distance, its mournful sound piercing the frosty darkness. It seemed to be crying for Daddy and for all the other soldiers and sailors and airmen who were so far away from home. I thought about the train that took us to meet Daddy in Brockville, and the other train that took him away to war. I wondered what he was doing at that very moment. Did he have turkey for Christmas dinner? Did he get any candy?

We’d sent him a parcel with his favorite black and green jellybeans in it, and some cigarettes and warm socks. I gave him an Agatha Christie book, Barbara a deck of cards and Roger a cribbage board. Did he get the things in time for Christmas? My lips moved in silent prayer, my breath making a small circle of mist on the cold windowpane.

‘God, please take care of Daddy. Keep him safe and end the war soon so that he can come home again.’Then I snuggled under the covers and closed my eyes. I could hear the muffled sounds coming from the RCA Victor console radio in the living room as Mother listened to the war-torn world welcoming in the year 1942.

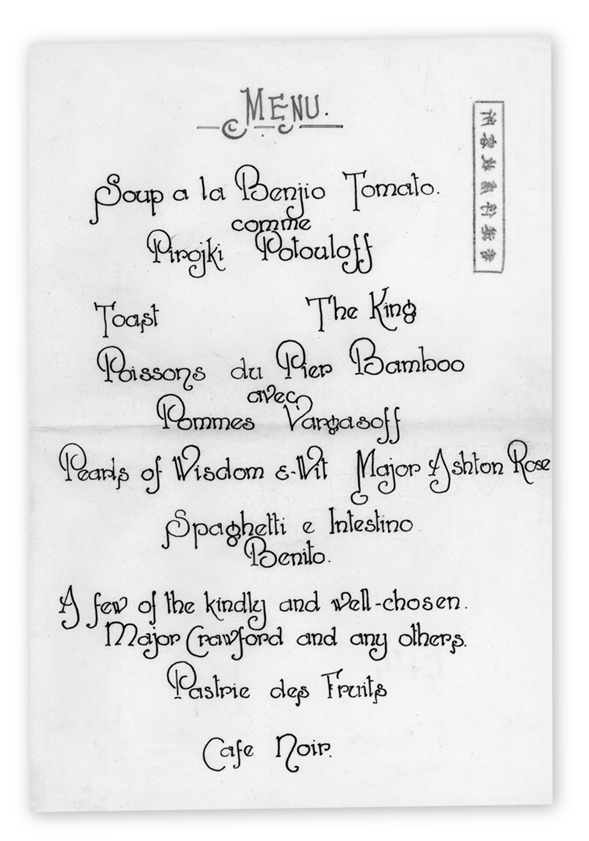

The Christmas menu from the Sham Shuipo camp on Hong Kong Island. Artfully styled, the menu shows how the prisoners attempted to make the best of a bad situation.