CHAPTER FIVE - Medicine Hat, 1941

Medicine Hat was a lot smaller than Winnipeg. From Aunt Edith’s house we could walk almost everywhere, even uptown.

There was a public bus service, but the city was so small that there were no specific bus stops. We were fascinated to discover that the bus went up and down every street, and if people were waiting by the roadside, the bus would stop and take them on board. When you wanted to get off the bus, you rang the bell and the driver would stop wherever you wished.

‘Medicine Hat is an awfully funny name,’ said Barbara. ‘Do you take your medicine out of a hat?’

Uncle Fred laughed.

‘No,’ he said. ‘The name comes from an old Cree legend.

Long ago, during a battle between the Blackfoot and Cree, a medicine man lost his eagle feather hat in the Saskatchewan River, so the Indians gave the city its name.’

The water of the Saskatchewan River is a beautiful blue-green colour, and very clear, just like a swimming pool. Looking down from the bridge, we could see right to the gravelly bottom.

This amazed us, as we were used to the muddy brown water of our Red and Assiniboine Rivers at home. There were also hills in Medicine Hat, and Mother and Aunt Edith huffed and puffed on hot days as they walked to the stores to buy groceries.

‘Stick to the sidewalks,’ Aunt Edith warned us. ‘Don’t take any shortcuts across vacant lots. You might come across a rattlesnake.’

‘Do they bite?’ I asked.

‘You bet they do,’ she said. ‘And a rattlesnake bite will kill you!’

‘What do they look like?’

‘They’re brown with white rings around their bodies, and they have rattles at the end of their tails.’

‘Like baby rattles?’

‘Well, they don’t look like baby rattles. They’re sort of bony growths. But when the snake shakes them they sound a bit like baby rattles.’

‘Why does he shake them?’

‘To warn little girls that they’re getting too close to him.’

That convinced me to follow Aunt Edith’s advice and stick to the sidewalks, and I never did meet a rattlesnake.

There was a wonderful pottery in Medicine Hat, and we loved to go there and watch the dishes and vases being made from the local clay. The clay was placed in molds and then baked in the kilns before being painted all colours of the rainbow. We were shocked, though, to see a boy come by with a wheelbarrow and a small axe and smash some of the creations. There was a great clatter as the broken pieces fell in to the wheelbarrow.

When we asked him why he was doing this, he explained that these pieces were defective and couldn’t be sold. I felt sorry for the broken pieces, and for the potters who had made them, but Aunt Edith said they were used to this as it happened every day.

Aunt Edith and Uncle Fred had two grown children. Irvine, who was in the army, no longer lived at home. Seventeen-year-old Marion had just finished high school and taken a job in an office downtown. Their large old frame house had a roomy veranda, and upstairs there was a porch off the master bedroom where Barbara and I loved to sleep on the hot summer nights. There was also a large garden that our uncle and aunt tended with great pride.

They grew lots of flowers and vegetables. Aunt Edith’s gladioli won prizes every year in the local flower show, and Uncle Fred’s potatoes were the biggest I had ever seen. Aunt Edith was a wonderful cook, and my favourite dessert was her mouth-watering lemon meringue pie. Barbara and I always argued over which of us got to lick the pot as we both loved lemon filling.

‘You’ll have to take turns,’ Aunt Edith said, but of course we always argued about whose turn it was, so finally we were each given a spoon and Aunt Edith would use a rubber scraper to divide the leftover filling into two fruit dishes, taking great care to dole out the exact same amount into each dish.

My passion for writing began on a huge Underwood typewriter much like this one.

Slight and wiry with twinkling brown eyes, Uncle Fred was a CPR trainman, and secretary for his union, The Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen. He had a colossal Underwood typewriter that sat on a big oak desk in a corner of the dining room, and to my delight he let me play with it. In no time at all I had composed a two-page newspaper, The Dorchester News, named after our street in Winnipeg. The feature story was ‘How the Dennis Family Spent Their Summer Holidays’.

HOW THE DENNIS FAMILY SPENT THEIR SUMMER HOLIDAYS

By Margaret Dennis

At the end of May my Daddy went to Brockville with the Grenadiers. Mummy wanted to be with him so we all went by train to Brockville. The train was very bumpy but we had fun eating in the dining car and talking to the soldiers. In Brockville we stayed at first in Mrs. Walters’s boarding house but it was not very nice there so we moved to a cabin by the river. Barbara and I met a bad man on the riverbank. What he did to us wasn’t very nice but Mummy says we’re not supposed to talk about it. After three days in Brockville we had to go back to Winnipeg because Daddy was being sent to Jamaica and that’s where he is now. We stayed in my Auntie’s house in Winnipeg because our own house was rented. Barbara got skarlit fever and had to go to the hospital for a whole month. Thank goodness Roger and I didn’t get it. When Barbara got out of the hospital she still remembered us. We came to Medicine Hat (isn’t that a funny name?) Now we are staying in Aunt Edith’s house.

My cousin Marion is seventeen. She is very pretty. She has curly brown hair and brown eyes. She has lots of boyfriends who are airmen training here to fight in the war.

Marion plays the piano and she and her boyfriends have fun singing songs about the war like The White Cliffs of Dover and There’ll Always be an England. Marion works in an office downtown and rides her bike to work every day.

My Uncle Fred works for the Canadian Pacific Railway. He is a trainman. Sometimes we go to the station to see him off. He is always the last person to get on the train. He pulls out his pocket watch to check the time and then he signals the engineer and the train begins to move and Uncle Fred grabs the rail and swings up onto the steps and waves good-bye to us. I’m always scared he’ll fall off but he hasn’t so far.

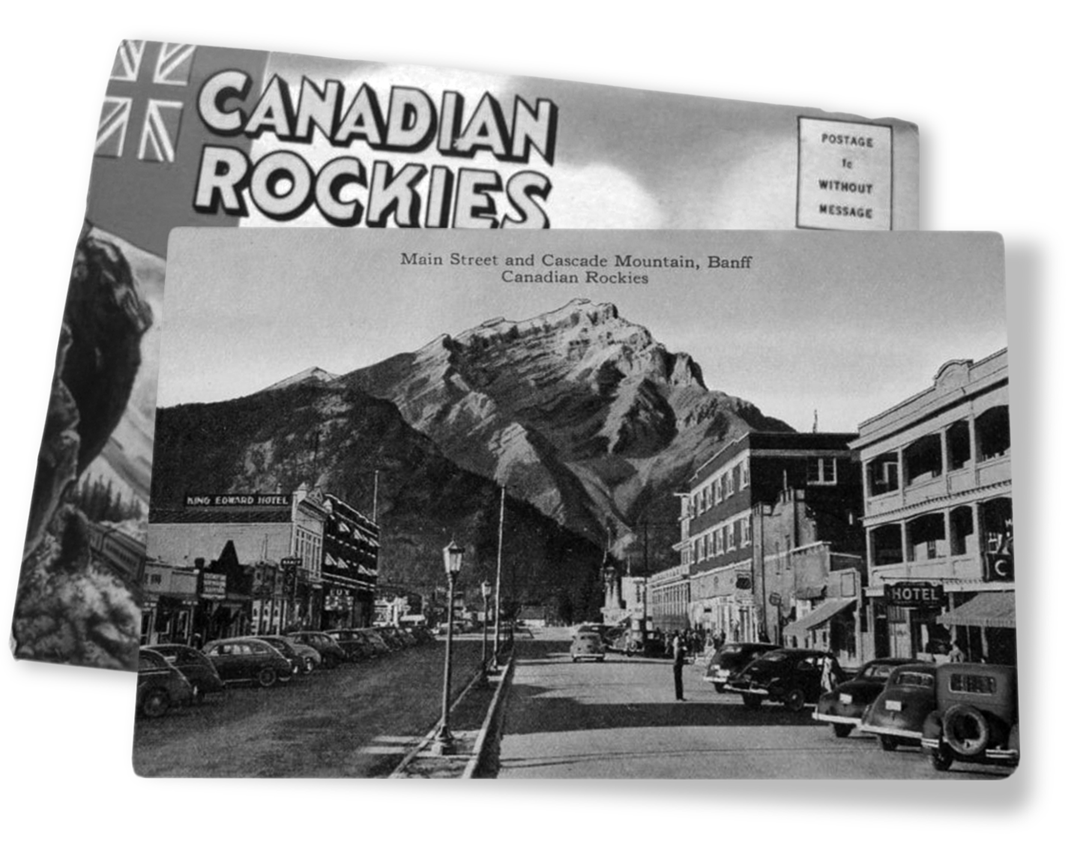

Last week Uncle Fred and Marion both had holidays so we all went to Banff on the train. We stayed in the Cascade Hotel.

It was night when we got there so we couldn’t see the mountains but the next morning Barbara and I looked out the hotel window and there was Cascade Mountain all covered with spruce trees. We couldn’t see the top of it because it was up in the clouds. Mother said that’s the first time she’s ever seen Barbara speechless.

We were in Banff for three days. We went to the Cave and Basin Pool and swam in the Sulphur Hot Springs. It smells like rotten eggs. We bought souvenirs in the shops — felt pennants, little birch bark canoes and postcards.

Now we have been in three provinces Ontario, Manitoba and Alberta this summer.

Mummy says enough of this, she’ll be glad to get back to her own house.

Because Daddy had visited Barbara in the hospital, he came down with scarlet fever shortly after his arrival in Jamaica. He was in the hospital for a month and was not allowed to send letters, so Mother didn’t hear from him for a long time. She grew tense and short-tempered, and one day she got really upset and spanked me on my bare bottom with a board from Uncle Fred’s workshop.

It was all Barbara’s fault too — I was just sitting on the veranda knitting a scarf for my doll, but Barbara grabbed my ball of wool and ran away with it, pulling the stitches off the needles. I screamed at her and Mother came running out of the house and dragged me down to the basement.

‘I won’t have you causing a disturbance in my sister’s house,’ she said.

I tried to tell her what happened but she wouldn’t listen. ‘You’re older than Barbara,’ she said, ‘and you should know better than to scream like that and upset everbody on the street.’

She grabbed the board and whacked me with it and then sent me to my room for the rest of the afternoon.

I lay on the bed and stared at the ceiling, tears running down my cheeks. It’s not fair, I thought. Everybody likes Barbara better than me. I made up my mind not to talk to Barbara anymore.

Then she’d be sorry. Then she’d wish she’d been nicer. To this day, I resent the fact that just because I was the eldest child I was supposed to be more responsible and take the blame for everything.

When Marion got home from work she saw me lying on my bed and came and sat beside me.

‘I heard what happened,’ she said. ‘Your mother is sorry she lost her temper. Why don’t you go down and talk to her?’

‘She likes Barbara better than me,’ I said.

‘No she doesn’t. She’s just upset because she hasn’t heard from your father for so long. Go and talk to her.’

I went slowly down the stairs. Mother was sitting alone in the living room, staring into space. I could tell she’d been crying as her eyes were red.

‘Come here,’ she said, patting the sofa beside her. ‘I’m sorry I lost my temper. I know that little sisters can be a pest sometimes. Bring me your knitting and I’ll fix it for you.’

I sat close to her as she picked up the dropped stitches and handed the knitting back to me. I could tell she was sorry, and I felt that she must love me at least a little bit.

Despite days like this, there were lots of fun things to do in Medicine Hat. We were surprised to find that all the streets went uphill and downhill. Just around the corner from Aunt Edith’s house was a park with a wading pool, and Mother allowed Barbara and me to go there every day, all by ourselves. And that wasn’t all.

Over on the next street, white-haired, toothless Mrs. Nicholson kept chickens in her back yard. Aunt Edith saved all her table scraps for chicken feed, and every morning we’d toss these over the fence to the scrambling, pecking hens. Those chickens would eat anything: apple cores, vegetable peelings, leftover toast, cold mashed potatoes, overripe strawberries — at every meal we left something on our plates to take to them. Sometimes Mrs. Nicholson let us help gather the eggs from the nests. She showed us how to slide our hands under the sitting hens to feel for eggs.

I was afraid of the pecking birds, but Barbara laughed at me.

‘Sissy. They’re only birds,’ she said. ‘They don’t have teeth so they can’t bite!’

Then Barbara would march up to a sitting hen. ‘Shoo, chicken,’ she’d say. ‘Give me your egg!’The hen would flutter from the nest, squawking in indignation.

‘See? They won’t hurt you,’ Mrs. Nicholson agreed, but I wasn’t reassured. I always waited until the hens had left their nests before gingerly picking up the eggs, warm and smeared with blood and chicken poop.

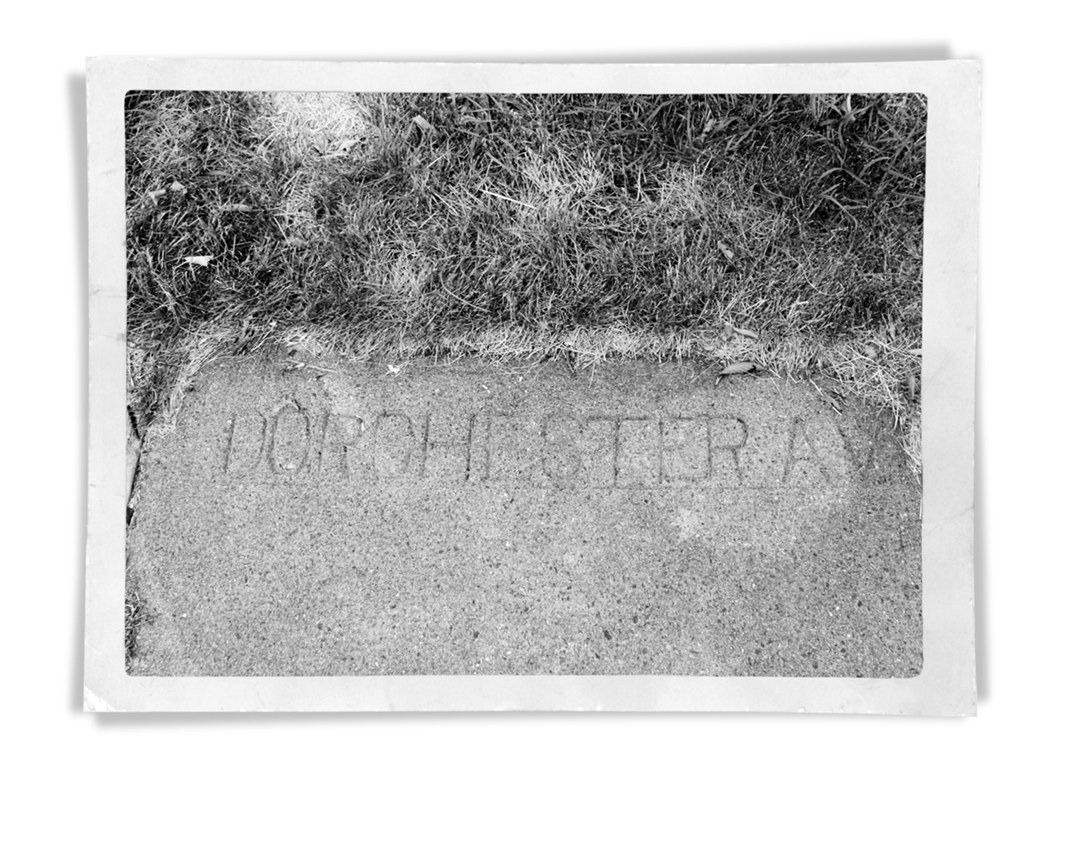

The name of our street was indelibly printed in concrete near the corner of Dorchester Avenue and Wilton Street.

At the end of August we returned to Winnipeg, just before the schools reopened. How wonderful it was to be back in our own brown and white frame house at 1033 Dorchester, sleeping in our own beds with all our own things around us once again!

At the beginning of September, Daddy wrote from Jamaica:

How is everything around the house, Dear? I hope you are feeling quite settled in again after your hectic summer. I hope you don’t get any cold weather. I expect we’ll feel the cold when we get home.

When are the schools going to reopen? Fancy Margaret in grade two! Our family is growing up, Dearest, isn’t it?