CHAPTER EIGHTEEN - The Homecoming

The war with Japan ended on August 15, 1945, just a week after I got home from Medicine Hat. Once again, Mr. Morgan took us downtown to see the celebrations, which were even more jubilant than those of VE Day — car horns honking, tickertape flying from windows, throngs of people cheering and shouting and hugging and kissing each other, and blowing up balloons.

The war was finally over, and all the troops would be returning home.

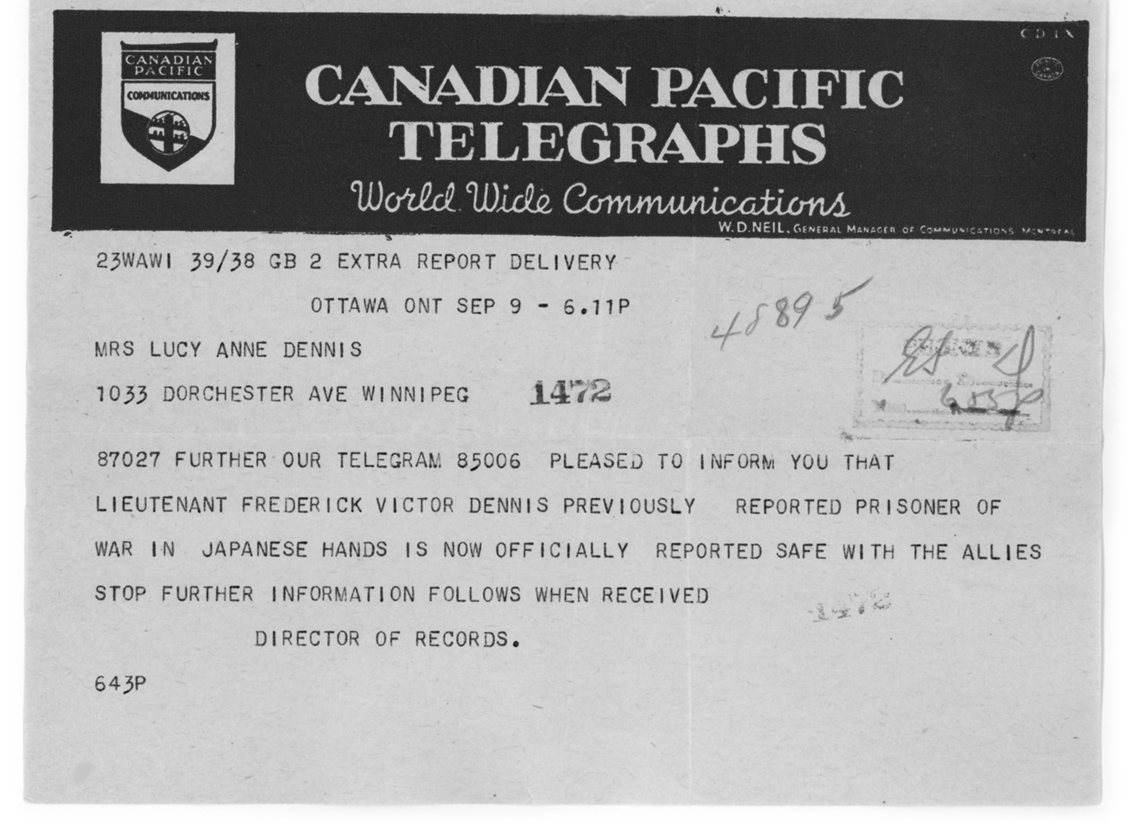

Not until September 9 did we receive the official telegram advising us of Daddy’s release from the prison camp. The men from the prison camps in Hong Kong, severely malnourished and underweight, were taken by ship to Manila where they enjoyed a time of rest and relaxation while waiting transport back to Canada. Daddy wrote to my sister and brother and me from Manila on September 16.

Dear Margaret, Barbara and Roger,

Many thanks for your letters just received. Tell Mummy that we are probably leaving here on Tuesday, September 18 by boat for Vancouver. You will receive a wire from there telling you the time of my arrival in Winnipeg. Of course I am just longing to see you all again.

I’m glad Margaret, that you had a good time in Medicine Hat. When I get home I shall have six weeks leave so we shall have lots of time to have lots of fun, won’t we?

I’m glad you are all doing so well in school. I guess I won’t have to spank you all first thing!!

How is the piano getting on? I am hoping you will be able to play for me when I get home, Margaret.

I hope you can all skate now. So you all have watches, do you? Well, you are better off than I am. My watch was all smashed up whilst fighting the Japanese. I shall have to buy so many things when I get home as I have absolutely nothing.

Tell Mummy that our parcels and cigarettes (sent at Christmas 1941) arrived in Hong Kong on February 27, 1945!

Well, bye bye for now and love to you all, Your loving Daddy.

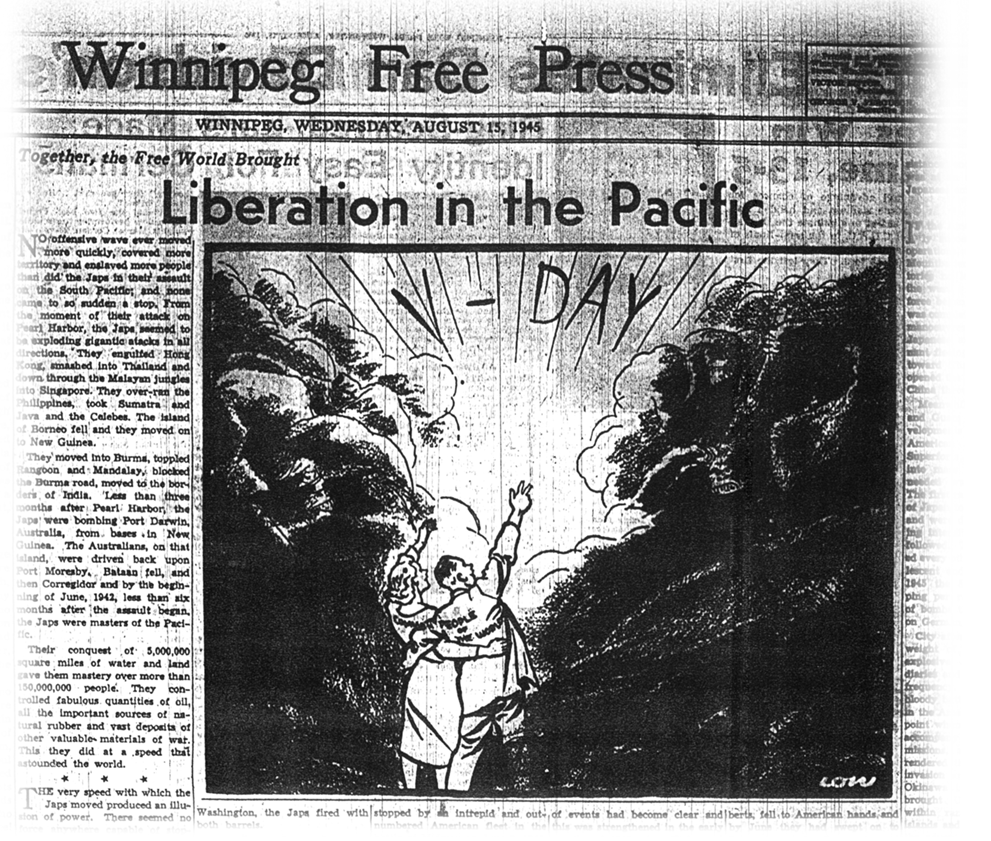

While The Winnipeg Free Press proclaimed the end of the war with Japan, reality came in the form of a telegram bringing the long awaited news that Lieutenant Dennis was finally on his way home.

Mother wrote Daddy a long welcome home letter.

Dearest Vic,

My heart is so full that I can hardly write to say ‘Welcome home to our dear Canada’! Every once in a while a wave of emotion sweeps over me and I just spill over and can’t keep the tears back. It seems so wonderful that you have been able to stand so much and are really coming home! I have had two letters from you, one written soon after the surrender and one on the Empress of Australia, and Margaret had one from Manila. Imagine you surviving diphtheria and beri-beri in those conditions! Dysentery we knew you would all suffer, of course. How you came through, God only knows.

Oh Darling! You will get such a kick out of the kids!!

Barbara is one of the most original, amusing children I have ever known, and she is getting so pretty. So is Margaret — very nice looking. I guess I’m prejudiced, eh Dear?

I am almost ready for you, Dear, but I am so excited and there is so much phoning etc. that preparations are moving forward slowly. I made fruit cake yesterday, and am making mustard pickles right now. Then there is a soap shortage so I had to start making my own laundry soap.

I had our bedroom papered in a lovely pale green, with peach-coloured sprays of flowers on it. I bought a pale green rug, too. The room is just beautiful. The ceiling is a pale peach, and I dyed the curtains peach to match. I am gradually getting everything in nice shape, so that you will have a real treat when you come in and walk around the place. You will know that if our finances can stand improvements to the house, I have been able to manage just fine. Mortgage and insurances and all other expenses are all paid up. The wall papering cost $12.00!

I am trying to gather some clothes for you but they are hard to find, especially decent socks and shirts. My Great West Policy matured this month so I have bought myself a nice black coat with a silver fox collar. If it’s a cold day I’ll wear it to meet you, but if it is nice weather I’ll be wearing a light brown suit which I tailored myself. I do all my own sewing now — you are going to be very proud when you see it, Dearie! Roger will likely wear his sailor suit which is pretty well gone now, but when I asked him if he’d like a new Sunday suit he said he’d rather wait and have Daddy take him to buy it because he would know the right kind to get! I can just see you two men ganging up on us females.

I would have loved to pick you up in the old car, but I decided to sell it last month and put the money into War Bonds. It was very old, and was start-ing to give me trouble, and I thought you’d like to buy a newer one when you get home. I got $150 for it, not bad for all the use we’ve had from it!

Every one of our friends is clamoring for the honour of driving you from the station but the Browns asked first. I am not asking them into the house afterward though — they know how we will feel! If you are able, we will have to be at home for a couple of hours the first day or the day after so people can drop in to see you. They have all been so interested and so kind to me. Barbara said, ‘There is such oceans of news it would take 9000 pages to get it all written out!”

So I will say good-bye for now, Darling, and God bless you till we meet. I know the emotional strain must be very great for you.

All my love, Dear,

Lucy

Newspapers served as a crucial link between servicemen and their families at home, providing snapshots of each others’ lives. (Click for detailed view).

Our grandparents in England were also overjoyed that Daddy was returning home.

He had written to his father from Manila, and in Grandpa’s response, dated September 30, 1945, he expressed his thankfulness, not only for Daddy’s release from prison, but also for Mother’s care and concern for the entire family.

My Dear Victor,

On returning home from the office today, I was very pleased to find your welcome letter. I am very glad indeed that you can say you have kept your health, but I expect a lot of building up will be required to bring you back to your prewar standard. Let’s hope it won’t take too long.

There is no doubt that Lucy has been a hero through all this, and we have special reason to be grateful to her because of all the trouble she took to think of us and our rationing.

Not only were the parcels she sent very welcome, but they showed how much thought she gave to the various selections.

You have a lot to make up to her for, and we have much reason to be thankful.

I hope you will build up quickly and be able to be reunited with your family, especially your wonderful wife.

Ever your affectionate Dad,

F.A. Dennis

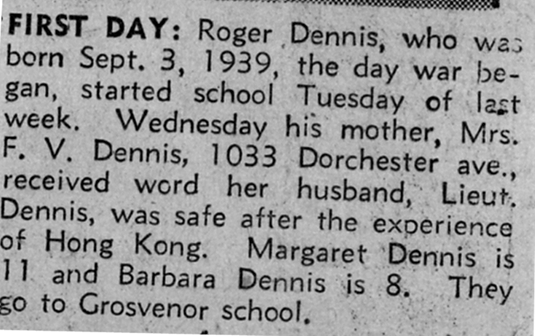

I had entered grade six that September, Barbara had started grade four, and Roger grade one. To celebrate the opening of school and the end of the war, The Winnipeg Tribune printed a photo of the three of us going off to our classes with the knowledge that our father would soon be home.

With Roger and Barbara, I posed on our front steps on Roger’s first day of school in September 1945.

I could hardly wait to see Daddy, but at the same time I was somewhat fearful. What would he be like? Mother told us that he’d be very tired and he’d need to rest a lot so we mustn’t bother him too much. He’d written me a letter saying he was looking forward to seeing me, but in one of his letters to Mother he’d asked: ‘Is Barbara as cheeky as ever? You tell her that I’ll use both belt and stick if she doesn’t stop!’

And he’d said in his last letter to us that he was glad to hear that we were doing well in school so he wouldn’t have to spank us all first thing. While I knew that he was joking, at the same time I felt that he meant what he said. He himself had been very strictly raised, and had attended boarding school in England from the time he was seven. As a result, he believed that children should be seen and not heard, and that they should be severely punished for any misbehaviour.

I’d never forgotten an incident that happened before he went away to war. I was just six years old on that rainy afternoon in June 1940. Forced by the weather to remain indoors, Barbara and I were playing with our Dionne Quintuplet cutout dolls at the dining room table. When I went upstairs to use the bathroom, I noticed that my parents were in their bedroom, all dressed up to go out. Mother wore a soft blue dress the colour of the sky. She had a matching hat, and white shoes, a white purse and white gloves. She looked so beautiful, but untouchable, like a princess made of ice.

Father was in full dress uniform, with his highly polished brown leather army belt that went over his shoulder and around his waist, and his peaked cap with its brightly shining brass Grenadier badge in the shape of a flaming grenade.

‘Are you going out?’ I asked.

‘Yes, we’re going to a reception at the mess,’ Mother said.

‘Isabel will look after you and give you supper.’

Isabel was our maid, a surly young farm girl who had come into the city looking for work. She had a bedroom in the attic and spent her days doing light housework and shouting at us to get out of her way. She didn’t like children, and we didn’t like her.

‘I don’t want to stay with Isabel,’ I cried. ‘You didn’t tell me you were going out.’

‘We don’t have to tell you everything,’ Mother said. ‘You’ll be all right with Isabel.’

For some reason, I had panicked. Perhaps it was because Father spent so little time at home, and Mother always seemed so preoccupied. Impulsively, I ran screaming down the stairs and across the veranda and out into the rain, slamming the screen door behind me. Hot tears poured down my face, mingled with the raindrops. I heard Mother and Father calling my name as I ducked between our house and the one next door and flattened myself against the wall beside the gray brick chimney. I gave myself away though; just as Father passed the house, I peeked out.

He saw me at once and dragged me back home. Furious, he took off his army belt, turned me over his knee and whipped me soundly across the backside.

‘Now maybe you’ll learn not to disobey us,’ he said as I stood in front of him, sobbing my heart out.

I didn’t disobey you, I thought. You didn’t tell me not to run away. But I was afraid to say anything. I was sent to my room and told to stay there until my parents returned home.

‘Isabel will bring your supper up to you,’ said Mother.

But when the tray arrived, Kraft dinner with buttered bread, I wasn’t hungry, so Isabel finished off my meal.

As a result, in the days before Daddy arrived home, I had many thoughts going through my head. I hoped that I wouldn’t do anything to make him angry, and that he would like me, and be glad to be back with us again. It was hard to concentrate on my schoolwork, but Miss Hallen was very strict, and made us stay after school if we hadn’t finished our work. I had to stay often, sometimes until nearly five o’clock.

Daddy finally arrived home on the evening of Monday, October 15, just a week before his forty-third birthday, and just ten days short of four years after he had gone away on October 25, 1941. Mr. and Mrs. Brown drove us to the CPR station that stood at Higgins Avenue and Main Street, right next to the Royal Alexandra Hotel where Aunt Betty once lived. Outside the station was the Countess of Dufferin, an old engine that we usually loved to climb on and pretend we were engineers, but that day we were too excited to even glance at it. As we waited in the station rotunda, we could hear the trains rumbling overhead.

‘Can we go up and see the trains?’ Roger asked.

‘Nobody is allowed on the platform,’ said Mother. ‘Daddy will come down those stairs. You watch for him.’

We stood behind Mother, watching the passengers come down the staircase. Most of them were civilians, but suddenly a man in uniform appeared, with the flaming brass grenade on the front of his cap.

‘Vic!’ Mother ran to meet him. We started to run after her, but Mrs. Brown held us back.

‘Let your mother greet him first,’ she said.

I wriggled free. ‘He’s OUR Daddy,’ I said as I ran to him.

Barbara and Roger had freed themselves, too, and were close behind me. Daddy wrapped his arms around all of us at once.

Mother was crying. We eyed our father curiously. He looked like his pictures, but was much thinner. As we were getting into the car he winked at me over the open door. All five of us rode in the back on the way home. Barbara sat on Daddy’s lap and Roger sat on Mother’s, and I sat between them, gazing shyly up at Daddy.

He kept winking at me and smiling, and he held my hand all the way home.

He likes me, I thought, he’s happy to see me again, and my fears vanished.

Since Daddy had left for Hong Kong, Mother had told us that if he came back safely we would be given a whole day off from school to celebrate, so the day after his arrival we had a holiday. All day we followed Daddy about the house, clinging to him and chattering in excitement about all the things we had done while he was away. We’d gone to the beach every summer, we told him. We’d gone skating and tobogganing, and to Cbristmas and birthday parties. We’d gone for drives in the car, and had picnics in the park and picked berries, and gone to church and to Sunday school and to the circus. All the things that Mother and we had written in letters to him were told over and over again, but since he hadn’t received many of those letters, he didn’t seem to mind our chattering.

We even tagged after him when he went to the bathroom, waiting outside the door until he emerged. We just couldn’t let him out of our sight. He seemed to lap up all the attention, although Mother told us after lunch that all of us, including Daddy, were to have a quiet time in our bedrooms for an hour.

So many friends dropped in to visit, bringing casseroles and soup and cakes and cookies and pies, that it was just like Christmas. Everyone told Daddy how happy they were to see him again, and how well Mother had coped while he was away.

‘Lucy is an amazing woman,’ they said, over and over.

‘I know,’ Daddy told them. ‘I’m very proud of her. It can’t have been easy, looking after the house and the children all by herself for such a long time.’

‘Well,’ Mother responded, ‘what I did was nothing compared to what Vic had to go through. He’s a strong man, and I’m extremely proud of him.’

Mother poured sherry for the guests, and made many pots of tea. There was lots of food, and all the friends and neighbours helped out by putting goodies on plates and passing them around.

Daddy had always been a quiet man, and he didn’t say much that day, but he beamed at Mother and us and all the guests; it was clear that he could hardly believe he was home again at last.

Finally, Mother said that we should go to bed.

‘You have to go back to school tomorrow,’ she said, ‘and you need your sleep.’

As I lay in my attic bedroom, listening to the chatter from the living room, I recalled all the evenings I’d lain awake in the silent house, wondering whether Mother was still alive downstairs. I got up and went over to the window and looked out at the autumn leaves glowing in the light from the street lamps, and the stars overhead shining down on our happy household.

‘Thank you God,’ I prayed. ‘Thank you for ending the wars, and for bringing Daddy home again.’

When I returned to school the next day, Miss Hallen demanded the obligatory note of explanation for my absence, although she knew full well what the reason was.

‘Well, Margaret,’ she sniffed. ‘It’s nice that your father is home again, but it’s too bad you had to miss an entire day of school because of it. Now you will have to catch up on all the work you missed yesterday!’

I had to stay after school to finish it all, but I didn’t mind. I didn’t mind doing arithmetic problems, I didn’t mind the stuffy classroom, and I didn’t even mind being harassed by Miss Hallen.

Our family was complete. Daddy was home with us again, and that was all that really mattered.

Together again: Victor and Lucy on the front steps of 1033 Dorchester Avenue.

My father returned from Hong Kong with a few unusal items: Christmas day menus; a photograph of Sham Shuipo camp and a shot from one of the skits the men performed to pass the time (all characters were played by men of course — even the convincingly dressed ‘woman’ sitting on the piano). (Click for detailed view)