Ernie's Story

"A Prisoner of War"

Burying the dead. Some terrible sights. Conditions are awful. Dead bodies lying around all over .... The stench is terrible. We put earth over some of the bodies.

These words are from the diary of Corporal Lance Ross of the Royal Rifles recorded during his first days at Sham Shui Po P.O.W. Camp.

It was into this hell that Ernie arrived on January 21, 1942. Only a month ago he had had surgery to remove the shrapnel that had pierced his side and lung at the battle of Wong Nei Chong Gap. Instead of recuperating in a warm hospital with good food, he was now facing a cold damp hut and near starvation rations as well as filth and very limited medical attention. After only two days, Ernie was moved to North Point, another P.O.W. camp. He recorded in his journal that he stayed there until September 1942.

North Point was on the waterfront of Hong Kong Island. It was built in 1937 to house Chinese refugees fleeing before the advancing Japanese. Due to heavy fighting in the area, the camp was almost destroyed. Some huts were completely demolished, others had missing roofs and broken windows, and there was no running water. In one part of the camp there were decomposing bodies of dead Chinese and animals. A garbage dump was breeding millions of flies. To the agony of cold and starvation was added lice, fleas and bedbugs. (Dave McIntosh, Hell on Earth, pp. 15-16.

It was a wreck.... It was as if they wanted to completely humiliate us. They told us quite bluntly that we had no honour, otherwise we would have committed suicide instead of surrendering. (Angus MacMillan in the 1987 submission to the U.N. Commission on Human Rights by the Hong Kong Veteran's Association of Canada)

Ernie had traded one hell for another that was just as bad if not worse. The poor food and lack of sanitation began to take its toll during the next few months. The food at North Point was described by various prisoners in Hell on Earth:

"The amount of rice at each meal was a cupful .... a teacup. It was usually crawling with maggots." "There was never enough food and you had to eat every bite or you wouldn't live. If you missed just one meal, it would knock you out .... We ate rats and we ate snakes too." "Once I remember we had a horse's head .... the cooks cleaned it all up and cooked the whole thing in a soup. It certainly provided a lot of grease that we needed, but I can remember one man going hysterical because he found a horse's tooth in his little bowl of soup." "The vegetables comprised a few dandelions, grass and weeds. It was common to see maggots in the rice and all kinds of little bugs." "It became a joke that the maggots were at least protein."Another prisoner who wished to remain anonymous told a horrible tale in Hell on Earth:

We all had diarrhea or dysentery or both a good deal of the time and knew that rice or barley could go through practically untouched. One day I was in such bad shape that .... I cupped my hands under a man squatting with diarrhea, caught the barley coming through, washed it off as best I could and ate it.It is hard to imagine Ernie in these brutal and primitive conditions. He had always put great emphasis on order and clean living as a young man in Scouts, the Church and the Militia. The pictures from Jamaica show him dressed in a neat spotless uniform at all times. But here he was a young officer, and a husband and a father of two sons, surrounded by filth, starvation, and disease. How he survived all this is the second story of his bravery. It was not the same kind of courage as he showed at Wong Nei Chong Gap. Perhaps it was an even greater test of his strength and spirit.

Among those who died at North Point was Colonel Sutcliff, a man Ernie had admired since his cadet days in Winnipeg. He died of dysentery on April 7, 1942.

Ernie's love for Irene and his hope to see his family again played a great part in keeping him alive. From December 25, 1941 until May 9, 1942 the prisoners were not allowed to send or receive mail. The Japanese did not co-operate with the Red Cross so that no one knew which Canadians were dead or alive.

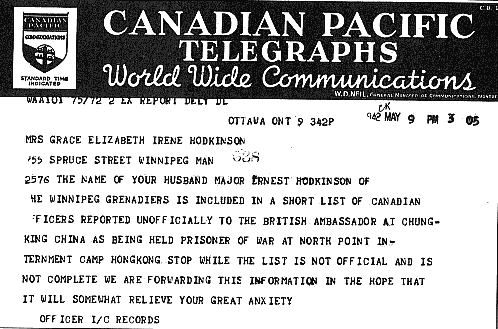

Finally in May 1942, Irene received the first news that Ernie might still be alive. It came in a telegram from the Canadian military saying:

The name of your husband Major Ernest Hodkinson, of the Winnepeg Grenadiers,

is included in a short list of Canadian officers reported unofficially

to the British Ambassador at Chunking China as being held at North Point

internment camp Hong Kong.

The name of your husband Major Ernest Hodkinson, of the Winnepeg Grenadiers,

is included in a short list of Canadian officers reported unofficially

to the British Ambassador at Chunking China as being held at North Point

internment camp Hong Kong.(Telegram from I/C Records)

Among Ernie's papers is a large collection of letters, cards, and telegrams both sent and received from May 1942 until September 1945. Irene's letters are full of everyday events about the boys' school and music lessons as well as news of other relatives. Just to know that normal life still existed must have been a great comfort to Ernie -- a reason to go on living.

Laurens Van der Post, who was a P.O.W. in Java, writes in The Night of the New Moon: The greatest psychological danger threatening men in the condition of imprisonment we had to endure, was the feeling that imprisonment was a complete break with their past and totally unconnected with their future.

Ernie's letters and later on the small cards allowed for P.O.W. correspondence say very little, probably due to censorship, but at least Irene knew he was still alive and well enough to write.

Ernie's records show he arrived back at Sham Shui Po on September 26, 1942. Dr. Stanley Banfill wrote in Hell on Earth:

We left North Point on the old Star Ferry. Those in the know must have been apprehensive because somewhere in our luggage was hidden a forbidden radio but we also carried something far more dangerous. Several of our men were complaining of sore throat; this was the beginning of a severe diptheria epidemic.Sham Shui Po was still a miserable place but it had one huge advantage over North Point as told by Lt. Tom Blackwood:

I have always said that the thing that made life tolerable in Hong Kong was the fact that we had a bountiful supply of good potable water for drinking, cooking, and showering. (Letter of September 17, 1997)At first the Japanese tried to make the P.O.W's work building a runway at Kai Tak airport but it became obvious that they were too ill.

"As more Canadians began to die of diptheria, the Japanese becamed alarmed. After all, their soldiers might catch it! They began swabbing throats - and insisted that everyone wear a face mask day and night." (Dr. Stanley Banfill, Hell On Earth)

The diptheria epidemic ended in early 1943 and also by then most battle wounds had healed. There remained the diseases of malnutrition - beri-beri and pellagra - as well as dysentery and malaria. Corporal Lance Ross writes about these diseases in his diary:

4 Oct. 42 - Another death in our company.... diptheria. The Japs won't give us any serum or medical supplies.

17 Oct. 42 - 6 more died last night and the Japs beat up about 40 of the orderlies, also Major Crawford. Made them take off their shirts - beat them with a wide rubber band.

18 Oct. 42 - The suffering is getting worse, men cry with painful feet, they cannot walk.

Morale was very low but slowly things began to change in the camp. The desire to rekindle their pride as soldiers and Canadians began to be felt amongst the P.O.W.'s. It was at this point that Ernie's strength and courage and all that training to be strong in adversity stood him in good stead.

The first thing that had raised morale was that the Japanese had allowed the men to send and receive mail. As the men once again began to feel a connection with their previous lives and also to hope for the future, they reinforced these attachments by organizing recreational and education programmes.

Ernie's first letter is dated June 3, 1942:

Dearest Irene and family,

I am very happy to be able to end your period of suspense by writing with some

good assurance of you receiving my letter. I feel sure something inside you

assured you my silence was only temporary.

I would like to have a snapshot or two of you and the children.... Filling time

is quite a problem but I am learning French and taking lots of exercise. Do not

worry about my health which is excellent.

All my love,

Yours

Ernie

The P.O.W.'s certainly did get lots of exercise especially those who were forced to work enlarging Kai Tak Airport.

We chopped down bloody mountains with pick and shovel and a wheelbarrow.... They shipped us over there in work details at seven in the morning. And we'd stay over there until six at night. (Bob Manchester, The Valour and the Horror)

Even though the Canadians had no choice but to help the Japanese build Kai Tak, they found a way to sabotage it by putting too much sand in the concrete which made it brittle.

The first Japanese aircraft to use the runway, a large fighter filled with dignitaries, crashed on landing. The Japanese engineer in charge of the project was decapitated. It was a sad victory in a long defeat. (The Valour and the Horror, p. 44)

The following is part of a song from Ernie's papers and shows the efforts to keep up morale:

The Road to Old Kai Tak

By the hazy hills of Hong Kong

(to the tune of The Road to Mandalay)

Looking down upon our guilt,

We are working on the airport

That the British should have built

For the wind is in the air sock

And the bombs are in the rack

Come and take old Kai Tak back.

Cutting grass and mixing concrete

Is the fate of slow Canucks

Who get trampled in the stampede

For a job on gravel trucks

When the casualties are counted

The remainder grimly hack

At the grass that grows profusely

On the field at old Kai Tak.

Besides learning French, Ernie was also learning Cantonese and Japanese. Lessons in both languages were printed in the Hong Kong News. Many neat clippings of these lessons are in Ernie's papers. There are also homemade Christmas cards and programmes for amateur entertainments.

Ernie told stories of bridge and chess tournaments and the compiling of recipe books. Once again all the Scout and Church activity gave Ernie a pattern that certainly contributed to his survival.

Another event that improved the lot of the P.O.W.'s was that the Japanese began to pay the men.

After about a year (end of 1942) the Japs paid us 10 sen a day which in our money at the time was worth only one Canadian cent. We never did know what they paid the officers but they did get paid. We never saw this money as it was pooled to help buy green tea, horse radish, or anything that put some flavour to the rice. Very, very seldom could they buy cigarettes. (letter from Lionel C. Speller, July 20, 1997)

The officers received somewhat more pay and Ernie kept the lists of the foods purchased for the individual huts during 1943. The items include:

Yellow Flower Fish

Sardines in Soya

Bean Curd

Lard

Margarine

Milk Powder

Onions

Tea

Salt, Pepper

Noodles

Cheap Cigarettes

Cigars

Matches

Shaving Soap

Razor Blades

No sizes are given, only prices, but any amount of tasty food would have improved the men's spirits as well as their health. These supplies were bought from the Chinese merchants in Hong Kong with permission from the Japanese. No one left camp to do this. It was done "through the fence".

In spite of the letters from home, recreational activities and the ability to buy small amounts of extra food, the men were still receiving little more that survival rations, diseases were still rampant, and Japanese brutality was a daily fact of life.

The Japanese code of honour was different from European ideals. A man who surrendered was despicable and deserved any amount of cruelty.

Laurens Van der Post, in his autobiographical novel The Night of the New Moon, describes the Japanese view this way: "They were instruments of ... revenge of history on the European invasion of the ancient worlds of the East... They never saw us as human beings but as provocative symbols of a detested past." In his other autobiographical novel A Bar of Shadow, Van der Post puts the Japanese point of view into the mouth of his P.O.W. Lawrence, speaking about the the brutal guard, Hara: "As a nation they romanticized death and self destruction as no other people ... Fulfillment of the national ideal ... was often a noble and stylilized self destruction in a selfless cause". Later he has Hara say to Lawrence: "Why are you alive? I would like you better if you were dead. How could an officer of your rank ever have allowed himself to fall alive into our hands? How can you bear disgrace? Why don't you kill yourself?"

Ernie told his family many stories of the brutality of the Japanese saying their actions seemed without specific cause - just the desire to torture and humiliate the P.O.W.'s.

He told of guards coming into a hut and randomly picking out a prisoner. This man might be beaten, made to stand in the hot sun until he fainted, or if the Japanese were really angry for some reason, he might be put into a small metal-roofed shed and left to "bake".

A strange bit of irony was present in the person of Kanao Inouye, know to the P.O.W.'s as the Kamloops Kid. Ernie often mentioned his cruelty and his hatred of Canadians. Kanao Inouye was born in Kamloops, British Columbia. He secretly left Canada and became an interpreter for the Japanese Army. He had been the victim of racial slurs by white Canadians in Kamloops.

Bob Clayton in The Valour and the Horror says:

We were lined up and all of a sudden this son of a bitch comes along... He's something new ... So he stops and says, "So you're Canadians, eh?" Just like that. "I want you to know that I was born and raised in Kamloops B.C. and I hate your goddam guts." He says that when he was a kid and growing up there, they'd called him "little yellow bastard" and stuff like this. He never forgot that.Even though the Kamloops Kid was able to revenge his hatred of Canadians because of the cruel way they had treated him as a child and young man in Kamloops, he paid for his crimes with his life. He was executed after the war for his misdeeds which included several murders.

Other Japanese brutalities included the use of slave labour especially at Kai Tak Airport. The Japanese threatened them with starvation if they refused to work.

Many prisoners were carried on stretchers from the camp to the airport by fellow prisoners and left to lie in the sun (or rain) all day with little or no food ("No work, no food" was the Japanese motto) until carried back in the evening. (from Hell on Earth, p. 29)

After the war ended, many stories were told of beatings, murders, and the deliberate withholding of medicines. It is hard to imagine how Ernie survived all this. In fact he almost didn't.

POW's Garden