Introduction

“A Prisoner of War: It is a Melancholy State”1

The Canadian participation in the Pacific Theatre during the Second World War is generally a footnote in this nation’s historiography, even its military historiography, and is not well known amongst the general Canadian public. The focus on the European Theatre of war is unsurprising considering the large number of soldiers committed there, and the important victories to which they contributed. No victory was to be had for the 1,975 Canadians who, in December 1941, engaged the Japanese at Hong Kong in Canada’s first major ground operation of the war. But their actions are no less worthy of study thereby. The two battalions sent to help defend the British colony had a war experience quite unlike that of their counterparts serving in Europe. Most were captured and, under the direst of circumstances, had to use a combination of mental and physical strategies just to survive. For Canadian prisoners in Hong Kong, real victory meant emerging from captivity alive.

The Winnipeg Grenadiers, the Royal Rifles of Canada (from Quebec), and a Brigade Headquarters, collectively known as “C” Force, arrived in Hong Kong on November 16, 1941 and joined their British and Indian comrades in what was assumed would be little more than garrison duty and a show of strength to ward off potential Japanese aggression. On December 8, Imperial Japan’s well-equipped and well-trained Twenty-Third Army, battle hardened from several years of operations in China, attacked mainland Hong Kong. On December 18, Japanese forces landed on Hong Kong Island, and the garrison surrendered on Christmas Day. The Battle of Hong Kong inflicted 100 per cent casualties on the Canadian units as every man (and the two nurses) were either killed, wounded, missing, or captured. A total of 1,684 Canadians became captives of a nation that did not recognize the Red Cross and had not signed the 1929 Geneva Convention concerning the treatment of prisoners of war (POWs). What followed for the Canadians were three years and eight months of psychological and physical abuse at the hands of their captors.

Conditions in the prison camps were deplorable as men had to contend with with flies, fleas, lice, rats, and a myriad of tropical and deficiency diseases. Prisoners had to live on approximately one-third of their regular caloric intake, their diet consisting of little more than rice and green vegetables, and if lucky, some fish or the contents from a rare Red Cross package. The captives also suffered without the benefit of proper medical care and every one of them was a hospital patient at some point during their captivity. Diphtheria killed 58 Canadians in 1942 alone, but dysentery, malaria, tuberculosis, parasitic worms, beriberi, and pellagra were consistently present as well. A total of 132 Canadians died while in Hong Kong camps, 136 more perished once transported to work in Japan. No fewer than 555 of the 1,973 men and two nurses who sailed to defend Hong Kong died in the Far East, a very high proportion considering results in other campaigns.2 However, 84 percent of the 1,684 initial captives survived the ordeal as prisoners in Hong Kong and Japan. Once one begins to understand what these men went through, it seems remarkable that so many of them managed to survive at all.

Accordingly, this is a work about survival. Veteran George MacDonell of the Royal Rifles believes that he and his “C” Force comrades had two missions: one to fight on the battlefield, and one to survive as prisoners. The first mission ended in defeat, but 1,418 prisoners completed the second mission. How precisely did these POWs manage to survive despite the obstacles that they faced? What kind of mental and physical strategies did they employ? How critical were factors such as morale, unit cohesion, and military training? What motivated soldiers to push on day after day? Most of the work on Canadian POWs in Hong Kong paints them as victims, and while they certainly were, a new work is needed that empowers them. This thesis is the first comprehensive synthesis that focuses exclusively on Canadian POWs who remained in Hong Kong from the end of 1941 until August 1945. It highlights the more positive aspects of their experiences and how those contributed to their survival. This work shows them to be industrious, clever, generous, proud, and committed to fulfilling their duties and returning home. They all had reasons to make it home alive. They all had reasons to complete the second mission.

The Battle of Hong Kong and the resulting POW experience for survivors has led to a rare bone of historiographical contention between Canada and Great Britain, and accordingly much of the literature is imprinted with anger and national bias.3 Two of the most prominent examples are The Fall of Hong Kong by Briton Tim Carew and Desperate Siege: The Battle of Hong Kong by Canadian Ted Ferguson. Something more recent from the Canadian side is Betrayal: Canadian Soldiers Hong Kong 1941 by Terry Meagher. 4 The latter author argues, as have others before him, that the Canadians at Hong Kong were betrayed twice, once by the Canadian government for sending them in the first place and a second time by their British comrades. In the years, and even minutes, after the battle, the two sides found a great deal of fault in each other’s front line performance. In Canada a great deal of anger has been directed at the Canadian government for the way the veterans have been treated in the years since. Perhaps the most well-known example is Carl Vincent’s No Reason Why: The Canadian Hong Kong Tragedy - An Examination, in which the author launches a blistering attack on the government’s decision to send “C” Force to the Pacific.5 In the 1950s, the Battle of Hong Kong was well-covered by the two nations’ official army histories, but the POW aspect was largely absent in both.6 Much has been written on Hong Kong since then, and though many works include both the battle and the POW experience, the tendency has been to go heavy on the former and light on the latter, even though the battle lasted a mere seventeen days while the POW nightmare lasted for 1,330 days. The POW experience has usually been relegated to a single chapter or part of the conclusion.7 However, since the 1990s, the POW experience has been separating itself from the larger battle narrative and has begun to find its own feet as a field. The growing literature covers a broad range that encompasses academic monographs, popular history, and personal memoirs.

Canadian works that covered prisoners in Hong Kong as a separate subject were uncommon until the 1980s. One of the first books to give the Hong Kong POWs more space was journalist Daniel Dancocks’s In Enemy Hands: Canadian Prisoners of War 1939-1945, published in 1983. Dancocks claimed that Canadian prisoners of war were the forgotten men of the Second World War. Arguing that the plight of Canadian POWs was mostly unknown to the Canadian public, Dancock’s intention was to give the reader an idea of what it was like to be a prisoner during the Second World War.8 More than 9,000 Canadians were POWs between 1939 and 1945, and Dancocks travelled across Canada to collect stories from 165 of them. His last three chapters provide a glimpse into POW life at the hands of Imperial Japan as the men described their ordeals as prisoners and forced labourers in Hong Kong and Japan; the interviewees are the real authors and Dancocks is merely the compiler. Though more descriptive than analytical, In Enemy Hands accomplishes the goal of making available raw and unfiltered human experiences. However, the section on Hong Kong is brief and there is little on important aspects of the POW experience, notably how the soldiers maintained morale and how they kept themselves occupied, two such themes that this thesis will discuss in detail.

In 1990 a unique cross-cultural work by two Canadian historians and two Japanese historians was published titled Mutual Hostages: Canadians and Japanese during the Second World War.9 The purpose was to show that both wartime Canada and Japan looked at the Japanese and Canadians under their respective control as “mutual hostages”. As Japan viewed its overseas interned citizens this way, according to the authors, it apparently tempered its policies towards prisoners under its control as a means of protecting Japanese nationals from recriminations. The Canadian government acted towards Japanese Canadians with the belief that any severe action against them could trigger reprisals against Canadians in Japanese hands. The authors lament in their introduction that, by 1990, very little had been written about Canadians who were Japanese captives in the Far East, a claim which was certainly true at that point. But Mutual Hostages itself falls short of presenting POW life under the Japanese.

Jonathan Vance’s Objects of Concern: Canadian Prisoners of War through the Twentieth Century does marginally better.10 Appearing in 1994, it traces a history of Canadian prisoners from before Confederation to the Korean War. The central argument is that POWs are not the forgotten or misunderstood casualties of war as is so often portrayed and implied in the literature. Vance examined how the Canadian government and various non-governmental agencies took steps to assist overseas prisoners, particularly through relief supply programs and attempted negotiations to secure their releases. He argues that every effort was made to alleviate the suffering of men and women in captivity, although he readily admitted that this was not always successful. One chapter is devoted to prisoners under the Japanese in the Second World War, whom Vance declares suffered the “deepest and most afflicting physical and emotional scars” of any Canadians imprisoned in any war this century.11 Vance adequately, though briefly, covers POW life under the Japanese but mainly takes exception to the notion that a more coordinated effort between the Allies could have greatly improved camp conditions for prisoners in the Pacific. As the Japanese had no intention of improving life for prisoners under their control, which weakens the ‘mutual hostages’ theory, there was little any organized effort could accomplish in dealing with a nation that, according to many, viewed its prisoners with contempt and only distributed relief supplies when it best suited its own purpose.12

In 1997 a book exclusively dealing with Canadian POWs in Japanese hands finally appeared. Former Legion Magazine staff writer David McIntosh’s Hell on Earth: Aging Faster, Dying Sooner, Canadian Prisoners of the Japanese During World War II,13 easily falls within the category of ‘angry national bias’. Half of McIntosh’s book is dedicated to driving the point across, in the starkest possible terms, that the Japanese brutalized their Canadian captives, while his secondary argument is that Canadian survivors of Japanese prison camps were betrayed by their own government after the war. Ottawa failed to provide adequate compensation and prevented veterans from suing the Japanese government for fear that litigation would upset an important trading relationship. McIntosh accused the Canadian government of giving “a much higher priority to its relations with Japan than its relations with some of its own citizens” and declared that the battle was a “British waste of Canadian manpower.”14 While passionately expressed, the book retains overtones of journalistic sensationalism and historical amateurism. And as with the previous works, much of the content concerns the plight of the Canadians in captivity and does not discuss how they survived that captivity, something this thesis seeks to correct.

In 2001, Dr. Charles Roland published Long Night’s Journey into Day: Prisoners of War in Hong Kong and Japan, 1941-1945,15 the culmination of a project Roland had been undertaking for more than twenty years. Roland taught at McMaster University for nearly two decades as a professor in both the Faculty of Health Sciences and the Department of History. Roland’s principle argument is that the Hong Kong POW story is an explicitly medical one that should be told by a medical historian. This contention makes sense if one considers that over a period of 191 weeks of incarceration every POW suffered a medical problem of one kind or another, with many of the men starving or seriously ill with little medical care available. Roland’s exceptional book is harrowing and uncompromising. But it has a broad range, covering prisoners from many nationalities in both Hong Kong and Japan And while survival and daily prisoner of war life is covered, it is not the focus.

Following in Roland’s imposing footsteps, in 2009 the independent scholar Tony Banham published an important work concerning the lives of Allied POWs under Japanese control. Banham already had established himself as an historian of the battle for Hong Kong with two previous works.16 We Shall Suffer There: Hong Kong's Defenders Imprisoned, 1942-45 completes Banham’s Hong Kong trilogy and continues the rich and informative work present in his two earlier books.17 Like Dancocks’s In Enemy Hands, Banham has assumed the role of curator while the prisoners are the real authors, and the POW experiences are shared through their own words. The book is a straightforward sequential recounting of POW experiences that focuses more on chronology and detail than analysis. By contrast, this thesis is more focused on analysis and addresses one issue not present in Banham’s work: how the men survived. Still, Banham’s work is absorbing.

Another independent scholar took on the subject with the 2010 book The Damned: The Canadians at the Battle of Hong Kong and the POW Experience, 1941-45.18 Nathan Greenfield notes that the Hong Kong veterans fought three battles: one on foreign fields, one in prison camps, and one against the Canadian government for restitution. The Damned aims to tell the story of the first two, while Greenfield also wishes to clear up some misconceptions: that the Canadians were poorly trained; that they were poorly led; and that they were duped into enlisting because of mindless nationalism. But, his account of the battle consumes two-thirds of the book, leaving the POW experience, as with many of the works cited earlier, lacking in substance and depth.

Still, Greenfield interviewed thirty former POWs for his book. In his hands the prisoner experience feels real and frightening, but there is also hope, resilience, and courage, traits generally absent in other works. This thesis will add to and expand on these themes and demonstrate that there were brighter moments that went together with the often-mentioned misery. Instead of focusing on death and dying, the present work will highlight the determination to survive and just how this was achieved. Additionally, Greenfield’s section on the POW experience focuses mainly on the men in Japan and the remaining captives in Hong Kong are only returned to periodically. This thesis will be specific to the men who remained in Hong Kong throughout the war.

Finally, for Canadian works, there are several outstanding veteran memoirs that have contributed to the field and that were of particular significance to the present study. William Allister’s Where Life and Death Hold Hands from 1989 was the first to be widely published. In 1961 Allister had penned A Handful of Rice. Though it is a fictional account of prisoners under the Japanese in Malaya, it was no doubt inspired by his experiences as a prisoner in Hong Kong and Japan.19 Allister was with the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals and his books, paintings, and willingness to speak publicly about his experiences made him a recognizable figure and veteran. Where Life and Death Hold Hands is more than a formulaic memoir. Allister’s narrative is almost storybook-like and his writing is at times casual. Some of the more unpleasant aspects of incarceration exist, but the story is interspersed with witty conversations, vivid and colourful descriptions, snappy remarks, and occasional jokes, something that differentiates it from the other memoirs. Allister does not shy away from the horrors of prisoner life, but he interweaves them with moments of overcoming those hardships and a willingness to confront them. Indeed, in his biography on the back cover of A Handful of Rice Allister calls prison life the “most horrible and rewarding experience of my life.” This thesis will build on these more positive moments and elaborate on them, showing them to be critical to the men’s survival.

Of the more serious variety of memoirs is One Soldier’s Story 1939-1945: From the Fall of Hong Kong to the Defeat of Japan by Royal Rifles veteran George MacDonell.20 MacDonell was one of only 11 members of “C” Force still alive as this thesis was written, and in 2015 was still well enough to make public appearances. The book is more a story of MacDonell’s whole life rather than just his time as a POW, although that is the framing component of the work. One Soldier’s Story is written in a simple, sincere tone that presents the experiences of battle and captivity in a touching, human manner. This memoir makes an excellent comparison with Allister’s in how two opposing styles can be effective at delivering the same message, that of perseverance and survival. Several other memoirs by Canadian veterans exist, but these are the finest.21 Additionally, some diaries have been published in their entireties, such as those by William Allister’s Corps of Signals comrade Georges Verreault and that of Winnipeg Grenadier Leonard Corrigan.22 There is also Letters to Harvelyn, a collection of letters that Major Kenneth Baird wrote to his wife and daughter while he was a prisoner in Hong Kong.23 All these published primary sources are thorough and contain vital information on how these respective men kept up their morale and remained as physically and mentally fit as possible, factors that are crucial for this current study.

Unsurprisingly, there are several British books about the battle and the POW experience. Both Tim Carew and Oliver Lindsay, who wrote on the battle with The Fall of Hong Kong and The Lasting Honour: The Fall of Hong Kong, 1941,24 respectively, returned with books on the POWs. Carew’s Hostages to Fortune is broken down into four chapters, but strangely only one of them covers the British at Sham Shui Po Camp (a British Army barracks that became the main POW camp), while the others deal with a lengthy recount of the battle, the sinking of the Japanese troopship Lisbon Maru that held many Commonwealth POWs, and the end of the war in Japan. The chapter “The Camp” lavishes praise on the British prisoners while excoriating the Canadians once they arrived at Sham Shui Po.25 A more balanced approach is Lindsay’s At the Going Down of the Sun: Hong Kong and South-East Asia 1941-1945.26 This book covers a lot of ground and is largely Anglocentric, although it does include a chapter on the Canadian prisoners who spent nine months of 1942 at North Point Camp, making it a rarity among British works. It is also presents a reasonably favourable portrait of the Canadians, another rarity for British writers.

Two of the most professionally written British accounts are G. B. Endacott’s Hong Kong Eclipse and Edwin Ride’s British Army Aid Group: Hong Kong Resistance 1942-1945.27 The former is a sweeping three-part general history that deals with Hong Kong before the battle, during the war (including the POW experience), and in the aftermath of the war. Considerable coverage is given to the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, something sorely needed in the historiography, but it leaves the sections on the battle and the POWs feeling rather compressed. The latter is an account of Ride’s father, Lieutenant Colonel Lindsay Ride, and his work with the British Army Aid Group who provided intelligence to POWs and helped organize escapes. While both offer plenty of insight into their corresponding topics, neither Canadians nor the prisoner-of-war experience in general are given much space.

As with members of C” Force, many former British POWs wrote memoirs on their experiences in Hong Kong. Several of them are principally concerned with fleeing from the prison camps, such as Escape Through China by David Bosanquet, a member of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps, and Escape from the Bloodied Sun by Captain Freddie Guest of the Middlesex Regiment.28 Amongst those dealing more with life as a POW is the unfortunately titled Prisoner of the Turnip Heads by George Wright-Nooth who was interned in the Stanley Prison Camp for civilians. As the title might suggest, the author is not one to forgive and this part diary, part memoir is laced with anger and contempt for the Japanese. One of the more recent additions is Resist to the End: Hong Kong, 1941-1945 by Charles Barman a Quartermaster Sergeant with the Royal Artillery who was held at the Argyle Street Camp for officers and later at Sham Shui Po.29 The book is largely based on Barman’s secret diary, but he reworked it after the war and it is difficult to tell what sections constitute the original material and which parts were added with the revisions. These memoirs cover many of the varied British military units in Hong Kong, but the authors’ interactions with Canadians are barely or not mentioned at all. Bosanquet only mentions the Canadians in the context of the battle, while Guest and Wright-Nooth do not cite them at all. Barman refers to them once, a comment on how the French-Canadian members of the Royal Rifles seems to be lacking the will to live. His language is obviously borrowed from Tim Carew who made the same assessment in Hostages to Fortune.30

Very few Americans were prisoners in Hong Kong. Those who were were mostly civilians, but there were some American merchant seamen. However, as befitting their large commitment in the region, there is a rich literature on the American prisoner experience during the Pacific War. A work with an exclusive focus on the Americans in Asia is E. Bartlett Kerr’s Surrender and Survival: The Experience of American POWs in the Pacific 1941-1945.31 Kerr’s father was one of 25,000 American prisoners of the Japanese and one of those who did not live to make it home. The author was inspired by visiting former POW camp sites in the Philippines and claimed that through his research into the sinking of the Oryoku Maru (the Japanese passenger ship that carried his father) he was dismayed to discover that a full account of American POWs was nowhere to be found. His book is an attempt to correct that oversight. Kerr examines not only prisoner life under the Japanese, but also the efforts of American aid agencies and the actions of US bombers and submarines which indirectly caused many of their own men’s deaths. And while it presents many of Imperial Japan’s atrocities, the book does not ignore American cruelty against the Japanese or the unsavory behaviour of some American POWs, including a rare instance of collaborating with the enemy.

Historian Gavan Daws spent ten years of research and interviewed hundreds of former POWs to complete his book Prisoners of the Japanese: POWs of World War II in the Pacific. Though his work covers many of the Allied nations, the author chose to focus on Americans for the “simple reason that Americans covered the whole range of the experience, across the broadest geographical sweep of territory.”32 Daws explores who the prisoners were, how they were taken captive, what happened to them in the prison camps, and how being a POW affected their later lives. The result is an absorbing narrative with a focal point on group bonding and survival. A similar work in the Canadian literature is lacking and this thesis seeks to correct that. Gaws also points an accusatory finger at the American government and official US histories for minimizing or neglecting the experience of their prisoners, something to which the Canadian POWs can relate.

Once literature on the Canadian involvement in the Battle of Hong Kong and its resulting POW experience began to appear in the 1980s, it has been produced with remarkable regularity ever since. This level of sustained interest is a bit peculiar given the Hong Kong campaign’s small size and its relative insignificance within the larger context of the Pacific War. Perhaps the prominence of this historiographical bias in Canada is fitting given that it was the nation’s only major engagement with the Japanese.33 The consistency of this production shows that even seventy years after the Second World War ended, the minor campaign at Hong Kong still elicits enthusiasm and curiosity from historians, journalists, veterans, family members, and an inquisitive public. But something is missing – a complete analysis of the men’s survival, physical and mental, and this thesis attempts to fill that gap.

This thesis relies heavily on prisoner diaries and these constitute the main source of evidence used in this work. The majority were examined at the Canadian War Museum’s Military History Research Centre in Ottawa. Three others held at Library and Archives Canada were also analyzed. The information gleaned from these sources is invaluable for studying the subject of Hong Kong POWs, and many works, including this thesis, would be next-to-impossible without them. The men who kept diaries in Japanese-run prisoner-of-war camps did so at great risk to themselves. At best, the discovery of one would result in its immediate confiscation. At worst, the offender would be harshly punished, especially if the diary detailed the brutal treatment meted out by the Japanese or if it contained disparaging remarks about Japanese soldiers; and they often did.34 In these diaries, the men wrote about the commonalities of prisoner life. They wrote about food, home, work, the weather, their pastimes, their health, their friends and fellow soldiers, and their Japanese incarcerators. Ultimately, they wrote about what was important to them, and their words served a dual purpose: to remind them of their experiences and to provide evidence of their captivity. Signalman Georges Verreault wrote on the first anniversary of his diary that it was his old friend, “to who[m] I confide all my feelings and thoughts. It relates my war, my imprisonment, rice, my hopes, my disappointments.”35 He carried it until the war ended.

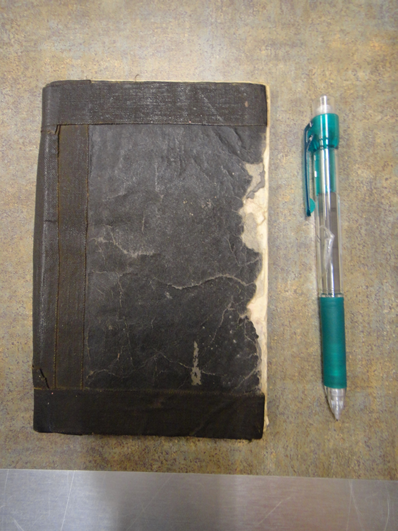

The notebooks used for diaries would have been smuggled into camp after the surrender. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine that the Japanese would have allowed the men to keep these as they often contained details about the battle and unflattering words about their opponents; therefore, the smaller the diary the better. Most of them, including Signalman Arthur Squires’s, were not much longer than a standard pen and only half that length in width, thereby making it easier to keep them hidden. Others improvised to record their thoughts. Lieutenant Collison Blaver of the Royal Rifles used an old British logbook for 1938 which he converted to serve his own purposes by altering the dates. Sergeant Frank Ebdon, also of the Royal Rifles, made his diary in late 1942 by using paper that he had been collecting over the previous few months.36 Rifleman James Flanagan kept his diary in separate parts, something that greatly benefitted him during a snap inspection in October 1942. The section that detailed his first ten months as a prisoner was taken away and never returned. Luckily, he did not suffer any repercussions. But Flanagan learned his lesson and hid the remaining sections, including his descriptions on the Battle of Hong Kong, in the lining of his boot reasoning that “they couldn’t take what they didn’t know existed.” He also learned to choose his words carefully, especially when describing the men’s treatment by the Japanese.37 Unsurprisingly, the greatest challenge of a clandestine diary was how to keep it hidden from the prying eyes of the camp guards.

Signalman William Allister kept his diary in the pocket of his greatcoat, which, in hindsight, was a terrible mistake. One day while using the latrines he hung his coat on the door but forgot it there and later returned to find it had disappeared, and the diary with it. Allister was forlorn and one of his fellow prisoners remarked that he looked as if he had lost his best friend; he practically had. However, this only inspired him to create a new diary by “sanding down two strips of wood with holes bored through them and looseleaf sheets of paper bound with a shoelace drawn through paper and wood.” Civilian George Porteous of the YMCA, who was also the Auxiliary Services Supervisor for the Winnipeg Grenadiers, provided him with the paper. Allister kept this new diary for the remainder of the war, hiding it “in many strange places.”38 In May 1944, frequent Japanese searches compelled Captain Lionel Hurd to hide his diary inside a can that was previously used to hold roofing tar. After the war, he was able to retrieve his diary, sticky but intact. Random searches also forced Winnipeg Grenadier Lieutenant Harry White to take desperate measures in hiding his diary: he buried it in the ground. However, as persistent rain caused him to fear that it would become ruined, he decided that it was better to keep it on his person despite the obvious risk involved. Another Grenadier lieutenant, Leonard Corrigan, also buried his diary, but for a much longer period. On August 17, 1945, with the war over, Corrigan recorded that he had spent the previous day recovering sections of his diary buried throughout the camp grounds. Some of it had “rotted to dust,” but fortunately most of it was undamaged and still legible.39

Not only had many of the diaries withstood captivity in Hong Kong, but several men who were transported to Japan managed to keep theirs hidden and unscathed until they were released. This was an impressive feat considering that the men were searched before boarding the ships that carried them to the Japanese home islands. Keeping a diary, under the most gruelling of circumstances, required bravery, determination, and ingenuity, three qualities that the Hong Kong POWs displayed in ample amounts. It is testimony to these courageous soldiers that we can piece together precisely what life was like for a prisoner of war under the Japanese. We know what they ate, how they were treated, how they kept themselves occupied, and most importantly, how they survived.

In addition to the diaries, other primary sources used for this thesis from the Canadian War Museum include letters written to and from family members, drawings, and random lists and notes that were made by the prisoners during captivity. Some documents were gleaned from Library and Archives Canada including, letters, memoirs, notebooks, medical reports, and the fonds of George Puddicombe, a lawyer who was a member of the Canadian Army War Crimes Investigation Unit’s legal team for the trials of Japanese officers and camp personnel accused of atrocities against Canadian prisoners of war in Asia. This thesis also uses interviews with former POWs collected by the Canadian War Museum, The Memory Project, and the Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association. Unpublished memoirs written by prison camp survivors also make a valuable contribution, as do personal narratives that were completed or written by family members. For example, Andy Flanagan and Michael Palmer wrote about their respective father and grandfather, Riflemen James Flanagan and George Palmer, while Edith Hodkinson wrote about her father-in-law, Winnipeg Grenadier Ernest Hodkinson.40 The intention of employing all these sources is to tell the story of Canadian survival in Hong Kong, as much as possible, by using the soldiers’ own words.

The opening chapter provides the contextual foundations for the thesis that follows. First, it places Hong Kong within the larger picture of the Second World War by looking at British military strategy in the Crown Colony and how it sought to thwart Japanese aggression. Then it discusses the Canadian government’s decision to send troops to Hong Kong and the subsequent deployment of “C” Force. The Commonwealth defences are examined before summarizing the Battle of Hong Kong and the events which led to Allied capitulation and the men’s imprisonment. Next, the chapter looks more closely at the Japanese victors, their disregard of the 1929 Geneva Convention on the treatment of prisoners of war, their Bushido mentality, and the physical abuse that they inflicted on their interned civilians and captured soldiers. Lastly, this chapter details the general conditions found in the prison camps and hospitals, including the lack of bare essentials, the nuisance of bugs and rodents, and the oppressive and unpredictable Hong Kong weather.

The second chapter begins this thesis’s examination of Canadian survival in Hong Kong prison camps by focusing on health and sickness. Food was of primary concern to prisoners and it constantly occupied their thoughts and dictated their actions. This chapter looks at how prisoners survived on little more than rice and vegetables and how they supplemented their meals through the black market, trade, and Red Cross supplies. It also shines a light on the importance of tobacco as a commodity in the prison camps and the practice of sharing in food and other goods between senior officers and their men. Next, the attention turns to disease and medical treatment to explore how the soldiers’ bodies were further ravaged by numerous ailments. Every man was sick at some point and some diseases, such as diphtheria in the fall of 1942, were responsible for many deaths within camp. The chapter concludes with a word on the medical officers and their remarkable ability to perform their work with a scarcity of medical tools and supplies.

The third chapter focuses on morale. Building on how the POWs physical bodies survived, this chapter explores the ways that they kept their mental state intact and stayed motivated to complete the second mission, the mission of survival. It begins with the significance of writing and receiving letters, and the complications that surrounded getting mail sent to and from Hong Kong. High morale complemented a strong will to live and the importance of hearing from loved ones cannot be understated. Next, this chapter will examine some of the physical objects kept by the soldiers and the value that they attached to them. The crucial themes of duty and discipline will follow, as will the critical role that senior officers played in galvanizing their men. Lastly, I look at two additional methods that the men used to strengthen their resolve: maintaining a sense of humour, plus the encouragement that they felt when US aircraft bombed Japanese targets in Hong Kong.

The fourth chapter combines mental and physical strengths and looks at how the men kept themselves busy for nearly four years. It describes the varied hobbies and pastimes undertaken by the men with special attention paid to how ingenuity and resourcefulness helped sporting and cultural activities thrive under difficult and hostile circumstances. Despite the harsh conditions it was often possible to learn a new language, play a game of ball, listen to a concert, or take in a play. This chapter also notes how the prisoners occupied themselves through work, whether as labour for Japanese projects or tending to their own camp gardens. A constant theme is how togetherness played an important role in alleviating boredom, and how the soldiers very importantly instilled a sense of normalcy under anything but normal conditions. Everyday things in life that are often taken for granted, such as playing cards or singing in a choir, could have a major effect on collective determination.

This thesis paints a picture of Canadian survival in Hong Kong prisoner-of-war camps. It demonstrates that the POWs survived because of themselves, but also because of each other. Who they were and what they believed in was critical to completing the second mission. The men of “C” Force had strong leadership and committed medical personnel. They also cared deeply about each other and never forgot their duty as soldiers. Critically, they worked hard to keep their physical and mental states strong. Perhaps most importantly, they were determined to return to their families. The prisoners who had a purpose or goal to achieve in the future, whether it was seeing a loved one again, starting a farm, or returning to school, were emboldened and therefore the most likely to survive. For the POWs, there needed to be a “why” connected to their survival. This thesis will show that the Canadians had a “why,” but it will also argue that the “how” was just as important to their survival.

1 Winston S. Churchill, A Roving Commission (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1930), quoted in Van Waterford, Prisoners of the Japanese in World War II (Jefferson: McFarland & Company Publishers, 1994), 33.

2 C. P. Stacey, Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War Volume 1: Six Years of War: The Army in Canada, Britain, and the Pacific (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1955), 488-89.

3 For a summary of the historiography and the debates about Hong Kong’s loss, see Galen Roger Perras, “Defeat Still Cries Aloud for Explanation: Explaining C Force’s Dispatch to Hong Kong,” Canadian Military Journal 11, no. 4 (Autumn 2011): 37-47. The author is critical of several books that use the horrors of the POW experience to attack the decision to reinforce Hong Kong without acknowledging the broader context of the Asia-Pacific region in 1941.

4 Tim Carew, The Fall of Hong Kong (London: Anthony Blond Ltd, 1961); Ted Ferguson, Desperate Siege: The Battle of Hong Kong (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 1980); Terry Meagher, Betrayal: Canadian Soldiers Hong Kong 1941 (Kemptville: Veterans Publications, 2015).

5 Carl Vincent, No Reason Why: The Canadian Hong Kong Tragedy - An Examination (Stittsville: Canada's Wings, 1981).

6 Stacey, Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War Volume 1; Stanley Kirby, The War Against Japan Volume 1: The Loss of Singapore (London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1957).

7 For example, Brereton Greenhous, "C" Force to Hong Kong: A Canadian Catastrophe, 1941-1945 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1997).

8 Daniel G. Dancocks, In Enemy Hands: Canadian Prisoners of War 1939-45 (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1983).

9 Patricia E. Roy, J. L. Granatstein, Masako Lino, and Hiroko Takamura, Mutual Hostages: Canadians and Japanese during the Second World War (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990).

10 Jonathan F. Vance, Objects of Concern: Canadian Prisoners of War through the Twentieth Century (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1994).

11 Ibid., 5-6.

12 Ibid., 215.

13 David McIntosh, Hell on Earth: Aging Faster, Dying Sooner, Canadian Prisoners of the Japanese During World War II (Whitby, Ontario: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited, 1997).

14 Ibid., vi.

15 Charles G. Roland, Long Night's Journey into Day: Prisoners of War in Hong Kong and Japan, 1941-1945 (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2001).

16 Tony Banham, Not the Slightest Chance: The Defence of Hong Kong (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2003); The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru: Britain’s Forgotten Wartime Tragedy (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006).

17 Tony Banham, We Shall Suffer There: Hong Kong's Defenders Imprisoned, 1942-45 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2009).

18 Nathan M. Greenfield, The Damned: The Canadians at the Battle of Hong Kong and the POW Experience, 1941-45 (Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers, 2010).

19 William Allister, Where Life and Death Hold Hands (Toronto: Stoddart, 1989); William Allister A Handful of Rice (London: Secker & Warburg, 1961).

20 George S. MacDonell, One Soldier's Story 1939-1945: From the Fall of Hong Kong to the Defeat of Japan (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2002).

21 See also: Kenneth Cambon, Guest of Hirohito (Vancouver: PW Press, 1990) and Leo Berard, 17 Days Until Christmas (Barrie: L.P. Bérard, 1997).

22 Georges “Blacky” Verreault, Diary of a Prisoner of War in Japan, 1941-1945 (Rimouski: Vero, 1995); Leonard B. Corrigan, The Diary of Lieut. Leonard B. Corrigan, Winnipeg Grenadiers, C Force: Prisoner-of-War in Hong Kong, 1941-1945, (s.l. : s.n., c2008), copy located in the Canadian War Museum Library.

23 Major Kenneth G. Baird, Letters to Harvelyn: From Japanese POW Camps – A Father’s Letters to His Young Daughter During World War II (Toronto: HarperCollins, 2002).

24 Tim Carew, The Fall of Hong Kong (London: Anthony Blond Ltd, 1961); Oliver Lindsay, The Lasting Honour: The Fall of Hong Kong, 1941 (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1971).

25 Tim Carew, Hostages to Fortune (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1971). Pages 72-74 are particularly critical of the Canadians and their conduct as prisoners.

26 Oliver Lindsay, At the Going Down of the Sun: Hong Kong and South-East Asia 1941-1945 (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1981).

27 G. B. Endacott, Hong Kong Eclipse (Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1978); Edwin Ride, British Army Aid Group: Hong Kong Resistance 1942-1945 (Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1981).

28 David Bosanquet, Escape Through China (London: Robert Hale, 1983); Captain Freddie Guest, Escape from the Bloodied Sun (London: Jarrolds, 1956).

29 George Wright-Nooth with Mark Adkin, Prisoner of the Turnip Heads (London: Leo Cooper, 1994); Stanley Wort, Prisoner of the Rising Sun (Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2009); Charles Barman, Resist to the End: Hong Kong, 1941-1945 (Aberdeen: Hong Kong University Press, 2009)

30 Barman, Resist to the End, 134; Carew, Hostages to Fortune, 96.

31 E. Bartlett Kerr, Surrender and Survival: The Experience of American POWs in the Pacific 1941-1945 (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1985).

32 Gavan Daws, Prisoners of the Japanese: POWs of World War II in the Pacific (New York: Quill, 1994), 26.

33 Though Hong Kong was the principal commitment for Canadian soldiers in the Pacific Theatre there were other contributions. Canadian pilots fought the Japanese in the Aleutians, the Royal Canadian Navy also participated in the Aleutian campaign, and over 5,000 Canadian troops participated in the (unopposed) invasion of Kiska in 1943. Additionally, Canadian air crew also operated in Burma.

34 For example, the officer in charge of the Hong Kong POW camps, Colonel Tokunaga Isao, was commonly referred to as a pig due to his large size.

35 Verreault, Diary of a Prisoner of War in Japan, 98.

36 Canadian War Museum Archives, 58A 1 259.8, Collison Alexander Blaver, Diary, 1942-1945; Library and Archives Canada, Frank William Ebdon Fonds, 1928-1980, Fonds Collection, MG30-E328 vol. 1, Diary entry for December 26, 1942.

37 Andy Flanagan, The Endless Battle: The Fall of Hong Kong and Canadian POWs in Imperial Japan (Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions, 2017), 70.

38 Allister, Where Life and Death Hold Hands, 54.

39 Diary of Captain E. L. Hurd quoted in Grant S. Garneau, The Royal Rifles of Canada in Hong Kong 1941-1945 (Carp: Baird O’Keefe Publishing, 2001), 199; Canadian War Museum Archives, 58A 1 24.4, Harry L. White, Diary, 1941-1945, August 7, 1943; Corrigan, The Diary of Lieut. Leonard B. Corrigan, 187.

40 Flanagan, The Endless Battle; Michael Palmer, Dark Side of the Sun: George Palmer and Canadian POWs in Hong Kong and the Omine Camp (Ottawa: Borealis Press, 2009); Edith Hodkinson, Ernie’s Story, [s.l. : s.n., 200?], located in the Canadian War Museum Library.