Conclusion

In Memory They All Survived

“But you must understand that our life was not altogether grim, at least not as grim as it was from the point of view of the sick. We had our lighter and happier moments, in which we forgot our misery and lived once more like civilized humans.”1

- Major John Crawford, Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps

The second mission was about survival and most of the Canadian prisoners of war in Hong Kong, and Japan, completed that mission. Their war ended on August 15, 1945 when Japanese Emperor Hirohito announced to his people that the fighting had ceased. The next day Harry White wrote that they had secured a Chinese newspaper and had it translated. “At last the great news,” he exclaimed. “Hell of a feeling in one’s chest, kind of choked up, many tears in evidence.” Leonard Corrigan wrote on the 17th that prisoners poured out onto the main road and engaged in “a big sing-song.” The same day Kenneth Baird found it impossible to put his feelings into words, but his thoughts immediately turned to those who had been killed or had died.2 On the 19th the chief Canadian and British medical officers, John Crawford and Leopold Ashton-Rose, were put in charge of the two remaining camps which housed soldiers. From the Japanese surrender it would be nearly four weeks until the arrival of Allied relieving forces and on September 16 Japanese forces in Hong Kong formally surrendered to the British Royal Navy.

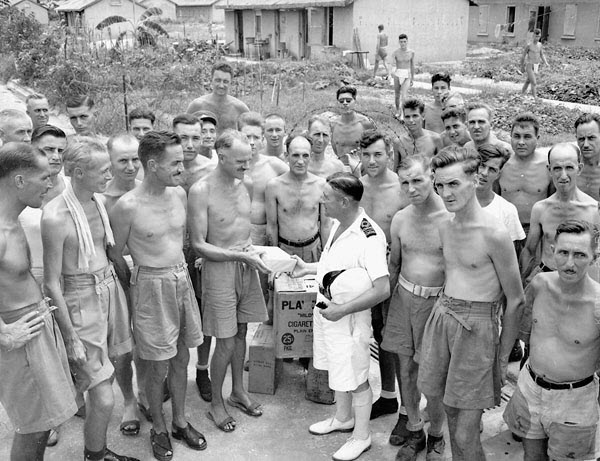

Commander Peter MacRitchie of HMCS Prince Robert meeting with liberated Canadian prisoners of war at Sham Shui Po Camp, September 1945. ©Library and Archives Canada. MIKAN no. 3617924.

Once liberated, the former POWs boarded the Canadian armed merchant cruiser HMCS Prince Robert. The ship that had escorted the men’s troopship on its journey to Hong Kong in 1941 was going to take them home four long years later. Prince Robert first called at Manila in the Philippines where American medical personnel evaluated the men’s health and cared for them. After the voyage home across the Pacific Ocean, the POWs arrived in San Francisco or Esquimalt, British Columbia where Prince Robert docked on October 20, 1945. Some had to be hospitalized or quarantined again, such as Francis Martyn who was still in a Vancouver hospital in November when he received a letter from his father that was dated October 14, 1945. The First World War veteran of the Winnipeg Grenadiers wrote to his son, “I’m so darn proud of you I could shout it from the hilltops, you beat me by over two years in the Army (guess I’ll never be able to live that one down ha ha), well you’ve certainly got what it takes to come through it.”3 When they were healthy the men could begin the often very long train journey back to their hometowns. Philip Doddridge, for example, arrived in San Francisco from Manila, boarded a train to Seattle, took a ferry to Victoria, another ferry to the BC mainland, and, after five days of waiting, a train to Montreal. In fact, it was more than three months after the war’s end before the last Canadian returned home.4 But they would make it home, and they were all with their families for Christmas 1945. They had much to celebrate that holiday season.

The members of “C” Force survived 1,330 days of captivity for several reasons. One predominant reason was the commitment of the medical staff. Dr. Crawford and his team performed their work in unimaginably difficult circumstances and it is largely due to their determined effort that more men did not die in the camps. But healthy bodies also need to be properly fed and many prisoners managed to eat just enough to survive. Through extra work, trade, or simply the generosity of their comrades, the men found ways to obtain extra sustenance. The carefully managed and widely shared Red Cross supplies made timely contributions to their health, as did produce from the communal gardens. Most of the Canadians held strong moral convictions about why they must survive. They had families that were relying on them to make it home. Letters from parents, wives, sons and daughters, and their own dreams for the future inspired the men to carry on. They had strong leadership in captivity and officers reminded them that they were still soldiers with responsibilities, and that they were still at war. Many did not need reminding. They worked together to alleviate boredom and instill a sense of normalcy in anything but normal conditions. Through it all they tried to keep their morale high and encouraged each other to do the same. Crucially, they did all of this together. It was kinship that led to Canadian survival in Hong Kong prisoner of war camps.

Men from all over Canada, and from many different walks of life, served with “C” Force. But the nature of their battle against the Japanese, and their subsequent imprisonment, did away with many of those divisions. In North Point and then Sham Shui Po most of the Canadians strove to create a shared camaraderie. Province of birth, religious background, social status, and education became unimportant as the men realized that, as prisoners of war, there was more that united them than separated them. Still, it was not entirely harmonious. There were cases of theft, there was resentment in the ranks, there were arguments, fights, and even suicides. But for the most part, being a prisoner of war in Hong Kong gave the men a shared goal of survival and that led to barriers being broken.

One of the most noteworthy examples was the relationship that developed between Georges Verreault and William Allister. Both were members of Brigade Headquarters and both were from Montreal, but their religious affiliations meant that their lives would be unlikely to intersect in 1940s Quebec. Verreault confessed in a June 1942 diary entry how this newfound friendship had caused him to re-evaluate a preconceived prejudice. “Strange! I used to despise Jews and now my best friend is a Jew,” he wrote. After a few months as prisoners, Verreault felt closer to Allister than he did to an old friend who was in Hong Kong with him. He even expressed how much he looked forward to meeting Allister’s family.5 They mention each other frequently in their respective diary and memoir. The shared difficulties of their captivity had created an unusual partnership, and one that likely never would have occurred outside these circumstances. They helped each other survive. The POW experience in Hong Kong changed some people for the better.

In a captivity marked by so much suffering and death it seems incredible that anything positive could have been taken away from the experience, but some of the former POWs do try to remember the better times. Perhaps it is a coping mechanism for living with the memories. One of the most positive reflections came from Dr. John Crawford. This, at first, seems peculiar considering that Crawford surely witnessed more death and misery than the average prisoner. But in 1946 he insisted that, above all else, he remembered the friends that he had made: “There were lots of people who were worth knowing, people from many strange corners of the earth who had been caught in Hong Kong along with the rest of us. When one rubs shoulders with people like that, one loses some of one’s corners, and learns what a cosmopolite really is.” Crawford maintained that he did not regret the experience and that he had learned a lot from it, principally the concept of tolerance, which he believed “in itself is an education.”6 Leslie Canivet, his facial scars from the battle still clearly visible in his 1995 interview, remarked that he also tried to remember the happier times, believing that this was a normal reaction for someone who has been through a traumatic experience. When asked how he would sum up his life, Canivet responded: “Well I wouldn’t change anything, except I would have preferred a better holiday in Hong Kong.”7 Tellingly, he does not lament that he was sent to Hong Kong, only that he wished the battlefield results had turned out differently.

Some were steadfast in their pride of having served their country, no matter the outcome. Corporal Alexander Henderson of the Winnipeg Grenadiers was more diplomatic than Canivet, and more serious: “I came out of it alive, anyway. I served my time as I had volunteered to do. We wound up over there, we did our bit, we made the best of it. You can’t have any feelings of resentment or regret about that.”8 Royal Rifles Sergeant James MacMillan also reflected with a degree of positivity, and humility, when asked in a 1996 interview how he felt about the war years:

I am pleased with myself for having served my country in a time of war. I volunteered to serve in the Canadian Army and chose which regiment to join, so I don’t have any regrets with what transpired following enlistment…It is claimed it was a mistake to send my regiment to Hong Kong, and maybe it was, but mistakes of many kinds are made in time of war…Incarceration as a P.O.W was long and difficult but some other Allied troops became P.O.W.’s in other theatres as well…I survived the war and internment and I am thankful for that.9

Often the men did not allow acrimony to fester. They moved on. Philip Doddridge, the current (2018) president of the Hong Kong Veterans Association of Canada, recalled that the time he spent in the prison camps gave him an opportunity to reflect on his life up to that point, and how he would change it when he got home. He went back to school and became a teacher.10

Doddridge, at 96 years of age, continues to be a voice for all Hong Kong veterans, living and deceased. Shortly after the men returned to Canada, various local associations were formed under the moniker “The Hong Kong Veterans Association.” The veterans believed that their special circumstances called for their own distinct organization, and these local associations were amalgamated to create six regional branches of the renamed Hong Kong Veterans Association of Canada (HKVAC). They would have much work to do. On September 8, 1951, Canada and 47 other nations signed The Treaty of San Francisco, also known as the Treaty of Peace with Japan. Article Sixteen concerned the allocation of compensation for prisoners of war and civilians who had suffered under the Japanese during the war. The article declared that Japan would pay the International Committee of the Red Cross which then had to distribute funds to the appropriate national agencies. The Canadian government reasoned that this article both granted sufficient reparations and negated its obligation to provide the former POWs with financial aid. The “C” Force veterans were justifiably outraged, but neither they, nor their organization gave up.

On August 20, 1965, the HKVAC ratified their constitution which outlined their principal aims and objectives: to assist all members in time of need, to maintain and improve the social welfare and friendship among members and dependants, and to promote legislation for the physical well-being of all members of all “C” Force or Allied personnel who were imprisoned by Japan between 1941 and 1945. Unsatisfied with the Canadian government’s response to the financial and medical burdens that they were suffering as a result of their long imprisonment, and disillusioned with the result of the San Francisco Treaty, the veterans decided that one final battle had to be fought: the battle for adequate compensation.

It was not until 1971 that the veterans were granted a 50 per cent pension for “undetermined disabilities.” In 1987, the veterans, in partnership with the War Amps of Canada, attempted to sue the Japanese government over the maltreatment that was meted out to their captives and the Japanese use of prisoners as slave labour. When Japan refused to provide compensation, the Canadian veterans took this demand to their own government. In 1998, the federal government paid 350 veterans and 400 widows the restitution that Japan was unwilling to pay. The payment amounted to approximately 18 dollars for each day the men were prisoners of the Japanese. Finally, in August 2001, the Canadian government announced that surviving members of “C” Force would receive a full disability pension and that veterans and widows from 1991 onwards would be party to the Veterans Independence Program.11 This program aims to help veterans remain in their homes, and in their communities, in a self-sufficient manner. It can also provide services such as housekeeping and in-home visits by health professionals. With these types of benefits established, the veterans and their families continued their fight to be remembered.

At the Hong Kong Veterans Association of Canada national convention in 1993, a proposal was tabled to create a new organization that would see the children of “C” Force veterans take the mantle from their parents. The intention was to educate Canadians on the Battle of Hong Kong and ensure that it, and its veterans, did not become forgotten in Canada’s Second World War history. In 1995, this group was dubbed the Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association and in 2001 it was merged with the original Hong Kong Veterans Association of Canada. The commemorative work is ongoing. On August 15, 2009, the Hong Kong Memorial Wall was unveiled at the corner of Sussex Drive and King Edward Avenue in Ottawa. The names of all 1,973 men and two women who served with “C” Force are engraved in the granite face. At the opening ceremony Philip Doddridge declared that “This is a permanent marker of our place in history.”12 And every year since, on December 8, the anniversary of the Japanese attack, a solemn ceremony of remembrance is held at the site to reconfirm that place in history.

The veterans of “C” Force are also remembered with a special addition to the Pacific Star. This Second World War medal was awarded to those British and Commonwealth soldiers who were on active service in the Pacific Theatre of Operations between December 8, 1941, and September 2, 1945. The yellow copper six-pointed star is adorned with a Royal monogram and topped with a crown. The ribbon’s coloured stripes symbolize forests, beaches, and the Army, Navy, and Air Force. To complement their Pacific Star, the Canadian government bestowed upon veterans a unique bar which is fastened around the base of the ribbon. Engraved with the words “Hong Kong” it denotes their involvement in the battle and recognizes them as a distinctive veterans’ group of Canada’s Second World War.

As of September 3, 2018, there were only 11 veterans of “C” Force still alive. Yet, when one understands what they went through, first in the battle and later as prisoners, it seems remarkable that any of them survived for decades, let alone that some lived to be over 90 years of age. Furthermore, freedom did not heal all wounds, and those who returned had to live with scars, both physical and emotional. Nearly every man who came back from the Far East had psychological problems associated with the years of brutality and undernourishment that they suffered while in captivity. Many of them would endure the effects for the rest of their lives. Dr. Charles Roland found that survivors returned with heavy emotional and physical complications, bringing home everything from nicotine addiction to intestinal parasites, and that the men “carried the seeds of restless dissatisfactions and dysfunctions that, for many, led to broken marriages, alcohol problems, difficulty in the workplace, and premature death.”13 In fact, the subtitle of Dave McIntosh’s Hell on Earth is “aging faster, dying sooner,” and he presents a shocking statistic: of the 1,418 prisoners liberated in 1945, 143 of them had died by 1965, by 1987 only 758 remained alive.14 Hong Kong veterans were indeed dying younger and in disproportionate numbers than any other Canadian veterans of the war.

However, when considering the nature of their captivity, this should not be surprising. Of the 290 Canadians deaths in Japanese prisoner of war camps, 256 were the direct result of disease, exacerbated or caused by malnutrition and the largely absent medical facilities. By contrast, in Europe only 29 of 380 Canadian prisoner deaths were from disease. The death rate for Canadian prisoners in Europe was around 7 per cent, while for those in the Pacific Theatre it was just above 17 per cent.15 Yet the Canadian survival rate in the Pacific was still higher than all other Allied prisoners of the Japanese. Historian Gavan Daws calculated that the total death rate for the over 140,000 Allied POWs was 27 per cent. The American, British, and Australian rates were all higher than 30 per cent, while the Dutch rate was just under 20 per cent.16 And, of the initial 1,684 Canadians taken prisoner at Hong Kong, 1,418 of them (or 84 per cent) completed the second mission and survived.

Despite many members of “C” Force aging faster and dying sooner, several of the soldiers discussed in this thesis went on to lead very long lives. Kenneth Cambon, Leonard Corrigan, Donald Geraghty, Ernie Hodkinson, James Macmillan, and Arthur Squires all lived past 80, with the latter two both living to be 89. Leo Berard, Leslie Canivet, John Crawford, Frank Ebdon, Thomas Forsyth, Lionel Hurd, Lance Ross, and Harry White all lived to be over 90. Philip Doddridge, George MacDonell, and Douglas Rees are still alive at the time of writing. Many of them also lived full and productive lives. They would not let their captivity define them and, in some cases, they used their wartime experiences as a catalyst for how they would live their future lives. Rifleman Kenneth Cambon, who was the youngest member of “C” Force in Hong Kong, was so inspired by the work that he performed as an orderly at Bowen Road Hospital that he attended McGill University’s medical school and graduated as a physician in 1951. Leo Berard continued to serve with the Winnipeg Grenadiers after the Second World War, working in Officer Training Schools and serving in the Korean War before retiring from the army in 1965. George MacDonell has been one of the most prominent and visible of the Hong Kong Veterans. After the war, he graduated from the University of Toronto, worked more than 30 years for General Electric, and served as a deputy minister in the Ontario Government from 1980 to 1985. He has written several works about his wartime experiences and has spoken widely to schools, groups, organizations, institutions, and at conferences to share his remarkable story. In 2005, at 83 years of age, he accompanied five other veterans on a pilgrimage to Sai Wan Commonwealth War Cemetery in Hong Kong, the resting place for 283 Canadians.

It was minus 14 degrees Celsius on the morning of December 8, 2018, and a light dusting of snow capped the memorial’s peaks which symbolize Hong Kong’s hilly terrain. But they still gathered, more than 50 people in all to honour “C” Force’s veterans on the 77th anniversary of the Battle of Hong Kong. Family members and friends of veterans, and representatives from the federal government, Veterans Affairs Canada, the Legion, the War Amps, the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps, and others all attended. Prayers were read, wreaths were laid, and tears were shed. “O Canada”, God Save the Queen, and the Last Post were played. And this author, with no personal connection to “C” Force other than this thesis, found himself caught up in the emotion of it all. I will always remember.

This has been a work about survival, and it is only fitting that the final word be given to one of “C” Force’s remaining survivors. When I met George MacDonell in Toronto in October 2016, he was 94 years old. I was immediately struck by how well he looked for his age. Here was a man who was wounded in the Battle of Hong Kong and lived through the brutal conditions of prisoner-of-war camps in both Hong Kong and Japan. Yet, MacDonell was still an imposing figure and moved feely about his apartment without assistance. He was quick to point out that Hong Kong should not be remembered as a defeat but remembered instead for how the soldiers fought and behaved against inconceivable odds. I had wondered if another work on Canada’s role in Hong Kong was necessary, but the meeting with MacDonell encouraged me that one more story needed to be told: the story of the second mission, a story of survival. MacDonell is proud to be one of the final representatives for his fallen comrades. And Canadians should be proud of him and all members of “C” Force. They lost one battle but won the more important second one.

1 Crawford, “A Medical Officer in Hong Kong,” 9.

2 CWM, White Diary, August 16, 1945; Corrigan, The Diary of Lieut. Leonard B. Corrigan, 187; Baird, Letters to Harvelyn, 261.

3 Canadian War Museum Archives, 58A 1 6.15, Francis Dennis Ford Martyn, Fonds, 1941-1945, letter dated October 14, 1945.

4 Greenfield, The Damned, 362.

5 Verreault, Diary of a Prisoner of War in Japan, 83.

6 Crawford, “A Medical Officer in Hong Kong,” 9-10.

7 CWM, Cavinet Interview, 1995.

8 Quoted in Dancocks, In Enemy Hands, 283-284.

9 Canadian War Museum Archives, 58A 1 271.2, James C. M. MacMillan, Postwar correspondence of POW James C. M. MacMillan, July 22, 1996.

10 The Memory Project Veteran Stories, Philip Doddridge, http://www.thememoryproject.com/stories/1396:philip-doddridge/.

11 Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association, Our Roots - the Hong Kong Veterans' Association, https://www.hkvca.ca/aboutus/hkvahist.php.

12 Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association, Creation and Evolution of HKVCA, https://www.hkvca.ca/aboutus/hkvcahist.php; Veterans Affairs Canada, Hong Kong Memorial Wall, https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/memorials/national-inventory-canadian-memorials/details/7933/.

13 Roland, Long Night's Journey into Day, 327.

14 McIntosh, Hell on Earth, 252-3.

15 Vance, Objects of Concern, 255-6.

16 Daws, Prisoners of the Japanese: POWs of World War II in the Pacific, 360.