Chapter 6

Prisoners of War - 1944

As Signalman Don Beaton said, “You can get used to anything. You can get used to being a prisoner, too.”[863] After two years as captives of the Japanese, most of the POWs had adapted in their own individual ways to the poor conditions, meagre food rations and camp and work routines. For the seven men of the R.C.C.S. in Hong Kong (even Ron Routledge in Stanley prison), and the eleven who were at Tokyo Camp 3D, there wasn’t a lot of change happening in their day-to-day lives as they began their third year of incarceration. In contrast, Ted Kurluk had just spent the past two weeks, including Christmas, being transported by ship to Japan. He would now begin the new year getting used to unfamiliar surroundings, rules and routines at his new camp.[864] Change was also going to come for the five Signals at Niigata 5B, in fact, in dramatic fashion.

Niigata Camp 5B, January, 1944

Around one o’clock in the morning January 1, 1944, the building in which I was quartered collapsed. Eight Canadians were killed and fifteen others beside myself were badly wounded. I was right in the middle of those who died, but my beri-beri saved my life.

If I slept normally, the water would go to my head during the night and my eyes were so swollen the next morning that I would not see anything. Therefore, I slept partially sitting up with my head against the wall. When the hut collapsed, a large beam fell at the end of the hut across nine of us in such a manner that eight of us had their heads crushed and died immediately. Since I was sitting up when I was sleeping, the beam hit me across the chest instead of on the head. This is how beri-beri saved my life….

I woke up with the beam across my chest and the beam was so heavy, that I could not breathe. I knew that I would die unless I turned on my side. I gathered all my strength and with a mighty effort turned on my side and then passed out. I came to again when four men were carrying me, two by the legs and two by the arms. They thought I was dead. I regained consciousness long enough to tell them “you’re pulling my arm off,” and then I passed out again. (Rolly D’Amours)[865]

Mel Keyworth was also injured during the collapse of the hut that night, caught under one of the roof beams.[866] Fellow Signalman Walter Jenkins escaped injury, but was there helping to rescue trapped POWs.[867] With 150 men in the building, it was amazing that more weren’t killed or seriously injured. Records confirmed that eight died and about twenty others were injured.[868] January 1 was deemed a holiday from work, but the next day a number of prisoners were put on the cleanup crew (removing wood, levelling the dirt floor).[869] Others were assigned to burial detail, placing the dead in crude coffins which were too short for the bodies.[870]

The Japanese, who by now had become masters at covering up and misrepresenting conditions in the prison camps, contacted Swiss officials in Tokyo, telling them that a typhoon had destroyed a barracks at Niigata, and informing them that there were Canadian POW casualties.[871] Later, there were stories circulating about heavy snow being the cause of the collapse, but diaries indicate there was little snow that night.[872] Shoddy construction methods and a poor foundation were the more likely cause. The medical officer, Major Stewart, said that some of the supporting struts had been removed to allow room for carts carrying excrement from the latrines to pass, so this may have also been a contributing factor.[873] Whatever the case, it was a devastating beginning for the new year at Niigata. Eight Canadian POWs were dead and many others like Rolly D’Amours (who turned thirty-three two days after the accident) were now incapacitated by serious injuries.

Of course, the Japanese offered no let up for the work crews. Every day, men who were sick or had minor injuries joined the rest of the POW labourers at the dockyard, the foundry or the coal docks. Men continued to die and morale was extremely low.[874] Walter Jenkins remembered his birthday that year – January 14, his twenty-third – because he went to the hospital that day. He figured that act may have saved his life because the doctor kept him from working during the cold and snow that winter.[875] Camp medical records indicate that he was suffering from beriberi and other ailments until mid-May.[876]

Some respite came on January 16 – a day off – and then the arrival of a Red Cross parcel on the 17th. Divided between two prisoners, each box contained corned beef, coffee, chocolate, salmon, paté, jam, milk, butter and cigarettes. “The first really pleasant thing that has happened since we landed in Japan,” wrote one POW.[877] The next day, Niigata Camp 5B was reorganized. The Shintetsu group of men (including Rolly D’Amours, Mel Keyworth and Ernie Dayton) went to a new camp closer to the foundry. This was designated Niigata 15B.[878] The others went to new accommodations nearby (still called Niigata 5B), which although overcrowded, offered some improvement due to the fact there were stoves for heat.[879] Men on the Rinko crew, like Howie Naylor, were able to smuggle in small lumps of coal.[880] Another positive for the men came in the form of an issue of towels, soap and toothbrushes.[881] Such minor conveniences even led a POW to say it was “the best camp yet.”[882] This in spite of poor sanitary facilities, lack of medicines, inadequate food, and the constant oppression of the Japanese guards. One instance of brutality that occurred about this time was recalled by numerous prisoners at Niigata 5B. A member of the Royal Rifles, James Mortimer, had been caught stealing food. Walter Jenkins described what happened:

They chained him out in the snow. They killed the American guy that was with him, they killed him. They knocked his brains out. But Mortimer they kept him out there till his feet froze and his hands froze and the doctor cut his fingers off with the scissors, you know. And they would stink like hell. He was in a little hospital where I was. He was the toughest son-of-a-bitch that ever lived, I think, and died. He was a tough bugger. He never – right to the very end – he didn’t moan or anything. He just said, “Them dirty bastards.”[883]

From all accounts, toughness was a prerequisite for survival. Rolly D’Amours, still recovering from his injuries including a broken upper arm (which had to be reset without any painkillers) was soon put back to work.

After a while, the cast was taken off and my arm was put in a sling. I was put on work detail clearing six inch thick ice from a road. We did this with pick and shovel. I used my right arm, which was in a sling, to hold the pick and with my left arm, I would swing the pick. I used the same method for the shovel.

All this time, the only shoes I had were pieces of straw and rags wrapped around my feet. One day, we were notified that shoes would be available at our place of work the next day. I went to regular work that day to get a pair of shoes. I got the shoes, but I was told that since I could walk to work, I would be on regular work detail at the foundry, from then on.

I was put to work cutting up tar and bringing it to the foundry. The Japanese were getting short on coal and were filling the boilers with a mixture of coal and tar. The man who owned the horse and wagon that was hauling the tar was a nice man and one day he allowed me to catch rotting daikons, (a vegetable) that were floating down the river. I built a fire, threw daikons in the fire to cook them. Then, after scraping the rotten part off, I ate them until I was so full I couldn’t eat any more. That night I had diarrhea all night.…[884]

Eventually, Rolly was put back to work in the foundry itself, shoveling coal into the boilers.

In the middle of March, a new camp commandant arrived at Niigata. He seemed to bring a somewhat more sympathetic approach to discipline – fewer indiscriminate beatings for example – and showed more interest in the welfare of the prisoners.[885] Red Cross food parcels were issued on March 23 (one shared between two men) and on the 28th other Red Cross supplies were given out, including wool blankets, gloves, socks, shirts and winter caps.[886] By early April the men had moved back into the previous camp, abandoned after the New Year’s Eve hut collapse. The buildings had been completed, a bath house, kitchen and running water added, and there was more room for the POWs in the barrack huts. Perhaps even more important for the welfare of the men was the establishment of regular rest days – four per month.[887] The rigorous work regime had been a major factor in so many men being off work (including Walter Jenkins, and Howie Naylor who was on the sick list from March 6-25 and again from April 21 to May 8).[888]

Two other things that helped to give a bit of a morale boost to the POWs that spring were permission to write a short note home on small cards issued by the Japanese, and the availability of the occasional hot bath.[889] The bath facilities were also made available, starting in late April, to the men from 15B, the foundry camp. So at least a couple of times a month Shintetsu workers like D’Amours, Dayton and Keyworth would have had a chance to see their Signals comrades at 5B.[890]

On May 9 there was a visit to Niigata by Swiss representatives who spent six hours inspecting the camps and interviewing prisoners. It’s likely the visit was arranged by the Japanese to occur after the above mentioned improvements had taken place. The Swiss noted that accommodation was satisfactory, prisoners had been allowed to write home, Red Cross parcels had been received, and rations were adequate. “Camp authorities have made numerous improvements,” the report said.[891] All in all, a glowing report!

Walter Jenkins rejoined the dockyard crew on May 18,[892] unloading boxcars of their cargoes of pig iron slabs, large sacks of soybeans, kegs of bean curd, and once, a shipment of bales of Japanese money.[893] Not only was the work exhausting, the men had to walk a mile and a half to and from the dockyard each day. One small incentive was provided by the dock company – rations from a large communal soup pot, “often a mixture of anything edible which was handy.”[894] Odds and ends of vegetables were scrounged and added, as well as the occasional bit of meat, even if it wasn’t very appetizing.

And one morning we were, we were coming down the track and here’s a big black cat that had been cut in two laying right on a rail. And, and Jenkins said, “That’s something for the soup.”[895]

By the summer of 1944, the warm weather and general improvement in the health of the men (only about fifty on the sick list, half the number from a few months earlier)[896] led to considerable improvement in the morale at Niigata 5B. They were also allowed to send a card home. Howie Naylor wrote on June 18:

My Dear Mother. Am in good health. Very happy to get your letters. Please send some pictures. How is dear Dad and rest of family? Am praying to be home with you soon. Will write Dad next time. Until then – Love to you all and my friends.[897]

Another positive development: the new commandant had allowed the purchase of some musical instruments and informal concerts were held on the camp “playground.”[898] Two American POWs organized and presented small plays. “Edie was a Lady” was well enjoyed, particularly by the Japanese camp staff, so much so that the commandant ordered the third act repeated.[899]

Through the fall months things remained fairly stable; it had now been more than a year since this group of Canadian POWs had arrived at Niigata and routines were well established. The sick list numbers remained relatively constant with a few regulars and others (including Walter Jenkins and Howie Naylor) off occasionally with the flu, colds, gastro enteritis, or other minor ailments.[900] However, in mid-December a number of dysentery cases began to appear. Fearing a major outbreak that would have reduced the available workforce considerably, the Japanese commandant ordered a work stoppage for two weeks.[901] About forty cases were diagnosed, including Jenkins on December 17 and Naylor on December 27. Both ended up in the isolation ward of the small camp hospital.[902]

Christmas, 1944 at Niigata was better than the previous year for a number of reasons: it was a holiday from work, the kitchen provided an improved menu that day, each man was given a Red Cross parcel, and, most important for some, there was a distribution of mail. A concert was held, including an amusing adaptation of Little Red Riding Hood.[903] A year that had started out so horribly had gradually offered some improvement for the POWs at Niigata. Their general health was somewhat better and the death rate had dropped significantly. News of allied success in the war had been filtering in as well, so morale was much higher than it had been at the end of 1943.[904]

Tokyo Camp 3D, January, 1944

For the POWs at 3D, the year began on a high note – a day off and a hot bath.[905] Then, on January 13, they were allowed to write a letter home. Don Penny:

My Dear Mother.

Another letter to let you know I am still in good health and am praying and hoping that you and the rest of the family are the same. Xmas is just over and we had a very good one. We got the day off from work and the Red Cross brought parcels in. Today I received a parcel of cigarettes from your group [9th Fortress Signals Women’s Auxiliary]. Will you please thank them for me. A few months ago I received the snaps that Dad took. You all certainly look swell. I would like a picture of Doug and Harry too. Am praying that Doug is doing fine and in good health. You will never know how I miss you all as it has been a long time since I left home. Well my Dear, keep your chin up through this trying time. Your loving son, Don.[906]

That same day, others also received parcels of cigarettes, courtesy of various Auxiliary groups in Canada. Letters home, parcels, and another hot bath. It was a banner day for most of the men at 3D.[907]

But not for Blacky Verreault. The previous day he had been off work because of an infection in one of his fingers. While resting on his bunk he was confronted by one of the Japanese guards. Blacky didn’t respond appropriately and was given the butt end of the guard’s rifle. The Montreal Signalman’s volatile temper got the best of him and he pushed the guard, knocking him down.

Shortly after, he returned with two more guards with their bayonettes threateningly pointed at me. They took me to the office of the commandant and since he was not there, they decided to be my temporary judges. A few shrieks to warm up and they started hitting me for the next ten minutes. I did not move although my skin was turning blue from the blows. It was cold and dark outdoors. The solitary box where West had been kept stood there in the snow. They took me to it, beating me on the way, then had me stand in it, at attention until 6 am the next morning when the commandant was due back. Every fifteen minutes they came to beat me up.[908]

Suffering from not only his injuries, but also a severe case of pneumonia, Blacky was transferred to hospital where he spent the next three months recuperating.

Will Allister later wrote about the cold winter weather that led to many cases of pneumonia, some of them fatal.

Winter…Back with its murderous winds, driving in from the ocean, attacking the miserable, cowering creatures crawling over the earth’s surface. It whistled through the huts whose poorly built rafters strained and creaked overhead. With winter the spirit went into hibernation. Fear and brooding took over. Pneumonia returned. Even speech grew spare as though opening one’s mouth let in the cold. Hope dried up like dead leaves.[909]

To make matters worse, on January 18 the Japanese cut off the small supply of coal that had been used for heat and cooking. Fuel wood was scrounged by the cooks from wherever it could be found, including the inside walls of the huts.[910]

By this time the prisoners knew very well that their only value to their captors was as much needed labour for the Japanese war machine. This reality had been used to advantage by Capt. Reid in getting necessary medicine and food rations to keep as many men as possible off the sick list. Work in the shipyard also created the only means by which the POWs could, in a small way, fight back against their oppressors. Certainly force was not an option, as Blacky Verreault and others had learned, often with dire consequences. Small acts of sabotage, however, had become a more subtle weapon, employing the skills and ingenuity of the Canadian soldier to upset, wherever possible, the Japanese war effort. Whether it was just a conscious effort towards low productivity (which Will Allister had developed into an art form with his slowness in all assigned tasks), the sparing use of oil in critical machinery,[911] stealing small supplies and tools,[912] or adding iron filings to the grease used to lubricate bearings,[913] most POWs were on the lookout for ways they could lessen their contribution, and celebrate (inwardly at least) small acts of subversion. Lee Speller recalled:

And every opportunity we got, because all their drills and their riveting machines, most of them, I shouldn’t say all of them were American-made, you see, so that if you could knock them over and they dropped down through the bottom of the weighs, they were broken, and they didn’t have the parts to have fixed them. So it held up production.[914]

On occasion there were more dramatic sabotage attempts. A fire at the shipyard on the night of January 18 burned the workers’ mess hall and the pattern shop above it. Although no specific cause was determined, it was generally understood that the fire had been deliberately set. Various stories about the origin and likely culprits circulated around the camp and the legendary status of the event persisted until well after the war was over. The fire caused an unscheduled holiday from work for the next two days,[915] but there were other consequences as well. Gerry Gerrard (who was able to celebrate his twenty-second birthday with a day off on the 19th), wished the men had been warned about the plan.

Even after we got back that night, because you knew all hell was going to break loose for a thing like that. And it did. The first thing next morning they came in and stood everybody to attention at their bunks and they started a thorough inspection. Well guys had all kinds of stuff they had stolen…I was right on the aisle, and my bag, at the top of it was a wooden Japanese lunchbox full of cigarettes. Because I was in the cigarette smuggling business. The commandant of the camp was wandering up and down and he actually pulled my bag apart a bit and sort of peered in, and I guess wouldn’t give a thought to a Japanese lunchbox – he saw them all the time – and so he just carried on. But I was thinking, “What am I going to do when these guys start searching my bag?” Well, at the foot of our bed was a space where you were supposed to put your shoes. I had a loose board under there where I used to hide these cigarettes. So I was watching for a time when there was no guard around, so I sort of get to it, and geez, by this time they were at the next bay [of bunks], so I said to the guys, “Give me a holler as soon as I’m clear,” and they gave me a holler and I reached back and grabbed the box, and them I held it down for a minute, and I got another chance and I got it tucked under that board. It was just that close! [916]

It was hard to know what negative effect the fire had on production at the shipyard, and although the men were back at work within a couple of days, the lack of a mess hall added at least one other unintended consequence:

…the men have to come into camp at noon for their noon meal, which means twice as much walking in a day as they previously had, and this time we are finding the double daily walk is causing a marked downhill course in those generally underfed and those with beriberi affecting the lower extremities. It is making the eternal problem of the working party much more difficult, with additional rests necessary for most men.[917]

It would be late February before the prisoners were again able to stay at the shipyard for lunch.

Events of the first few days of February provided another demonstration of the ever shifting lows and highs that characterized life as a POW at 3D. Two men died on the 1st and then another on the 2nd.[918] But the gloom of losing three comrades in two days was then immediately turned around by the arrival of about 1500 letters in camp.[919] Gerry Gerrard received six letters in four days.[920] Don Penny was almost as fortunate – five letters from home, all on February 2. One had been in transit for almost eighteen months; the others had been sent between January and May, 1943. All were mailed before the restrictions on length, so were filled with details about what was happening to the Penny family back in Vancouver. It’s easy to imagine Don’s reaction when he read his mother’s words, “I certainly hope I will receive letters from you. If I could only hear that you were well how happy I would be.”[921] How many other mothers had written similar lines over the past months?

Personal parcels also occasionally, as Will Allister put it, “found [their] way miraculously, to 3D”

I couldn’t believe my luck. My eyes feasted on the new riches as I lifted out each item…two top quality officer’s shirts, two pairs of woolen socks, shaving brush, razor, soap, toothbrush, toothpowder, shoes! Greatest prize was my favourite angora sweater. It would keep me warm![922]

In late February, Blacky Verreault, while recuperating from his pneumonia, was another one of the lucky recipients of a parcel from home. “It was a blessing and I sold all the clothes except a pair of shoes. I bought salt, spices and cigarettes with the proceeds.”[923] Blacky’s decision reflected two high priorities for POW slave labourers in Japan: food and feet.

Around this time Capt. Reid noted the problem of lack of proper footwear: “…although there are Red Cross shoes in camp the Japanese refuse to release them to us as yet.”[924] It wasn’t until mid-April that two hundred pairs of boots were distributed, and even then, fifty pairs of Japanese boots being used by the prisoners had to be turned over in exchange. Towels, gloves, handkerchiefs, sweaters, underwear, pajamas and socks were also issued.[925] Gerry Gerrard recalled his own boot experience:

I think the Red Cross sent shoes a couple of times, but there wasn’t enough to go around, so they said the ones with the best work attendance got the shoes, so I got a new pair. I really took care of these shoes – we’d get wax off the slips and I’d wax these boots – I really looked after them. And the next time they brought shoes in again they said you get another pair of shoes. Well I said I don’t need another pair, I’ve got a good pair, give them to somebody else. But they said no, you take the new ones and we’ll give the old ones to somebody else. So I had to take the new ones again. So for most of the prison time I did all right for boots. Of course. we wore these wooden clogs most of the time, I just wore the boots for work. Probably helped my feet quite a bit.[926]

The footwear situation also created an opportunity for Lee Speller. With experience in the shoemaking trade back in Victoria, he was eventually moved from his rivet-crew job in the shipyard to set up a shoe repair shop in the camp.

Anyway, we had quite a little shop. Sometimes there would be as many as four or five of us. Because all they were doing was providing canvas shoes with a [split toe]. And of course it all had to be sewn by hand. And here I was, showing our boys how to, and sometimes we were up until midnight, because they were determined to get them to go to work, you see. Capt. Reid wouldn’t let them go to work unless they had shoes on. Whether they were wooden or whatever. This is why we had to work sometimes till midnight to keep their footwear. And I was there until the camp broke up.[927]

Other Signals POWs also benefitted from having special talents which at least occasionally took them away from more rigorous work. Jim Mitchell put his mechanical skills to good use repairing clocks and watches, both for his fellow POWs and for the Japanese at the shipyard.[928] Will Allister’s artistic abilities had been recognized and appreciated by the paint crew foreman. For one short but delightful period in his life as a POW, Will was given art supplies and put to work painting various subjects and scenes from photographs selected by his Japanese master. He also was allowed to put his dramatic training to use, as he had in Hong Kong, coordinating shows for radio broadcasts from camp.[929] But unfortunately for most of the men, there were few if any opportunities to escape from their daily toil in the shipyard and the harsh realities of life as a POW.

At 3D, one of those realities during the late winter and early spring of 1944 was more death, primarily due to pneumonia. One of the victims was S/Sgt. Lyle Ellis, the leader of Section #7 which included a number of Signals. His passing was felt deeply by many in the camp, including Capt. Reid who wrote: “One has lived now so long with these boys that their deaths are very trying and haunting.”[930] While alone at night on fire piquet duty, Will Allister mused on Ellis’ death that day, reflecting what seemed to be a general malaise at the time.

And would we really survive even if we lived? Would there be anything left worth saving? Weren’t we being subtly murdered now by inches? We were not just standing still, marking time as we imagined. We were being invisibly destroyed day by day from within. Death was a tricky customer. He was not only inside this coffin, relaxed, fulfilled, cosying up to Lyle Ellis, he was everywhere, relentlessly, patiently dogging our footsteps, sitting beside us as we worked, ate, slept, stealing our humanity. Was there any defence against him? Only time would tell.[931]

The camp commandant also became concerned about the number of men dying or who had become seriously ill. About the same time as Ellis’ death, he issued 433 tins of meat that had been held back from the earlier issue of Red Cross supplies. He also released 220 blankets for use in the huts to help keep the men warm.[932]

March 23 brought an even more welcome distribution: more mail from home. Among the happy recipients were Don Penny and Gerry Gerrard, who each received seven on that one occasion. Don’s letters, two from his Dad, five from his Mother, had all been sent between January and May, 1943 (before the 25-word restriction was put into effect), and included one written precisely a year prior to the day he received it. A month later, he was able to respond to all the news.

April 22nd

My Dear Mother,

A short note to let you know I am still in good health. Hoping and praying that you and family are the same. Received few of your letters. Sorry to hear of Grandad dying. Pictures Dad sent are my only treasured possession. You all look swell. Glad Dad is doing so well but shouldn’t work so hard. Glad Doc is doing fine. Am very proud of him. Hope Doug is safe and in good health. Am longing to be with you all again. Have a great many plans involving you and Dad so just have to get back. All for now my dear and please don’t worry. Your loving son Don.[933]

Like all POW letter writers, Don had no idea if or when it would reach the hands of his family. In this case, it would be almost eighteen months, arriving in Vancouver on September 17, 1945. Sadly, his mother would never see it. She died of complications following a stroke a few months after Don wrote the letter.

Promise of more immediate communication with Canada came with the preparation of sixty-five radio messages on April 24-25.[934] Although the POWs, including Signalman George Grant whose words were directed to his wife and mother,[935] didn’t know if the messages would ever be broadcast, they were hopeful that their greetings to family and friends, and the list of names of fellow POWs read into the microphone would soon be heard back in Canada.

Canada, May, 1944

Department of National Defence

16th May, 1944

Mr. James A. Penny

3256 West 2nd Ave.,

Vancouver, B.C.

Dear Mr. Penny:

The attached message has been received from an unofficial source and consequently this Department cannot vouch for its authenticity. It should be remembered that the enemy has control over the preparation and transmission of such messages and the contents should be treated accordingly.

The names of all prisoners of war mentioned in such messages are identified (when possible) from the official lists and then the next-of-kin are notified by this Office.

This message is forwarded in the belief that it will be of particular interest to you.

Yours sincerely,

(F.W. Clarke) Colonel

Spec’l Asst. to the Adjt.-General

Date message received – 8th May, 1944.

Message purports to come from –

H-6762 Pte. Jack S. GOODY

Cdn. POW – Tokyo Camp, Japan.

“My dearest Mother, Dad and family. I have been given this opportunity by the Japanese authorities to send to you a message of love and condolences. Up till now I have been in the best of health. I have received quite a few letters from you and the Gills and also a parcel. I would like to mention a few of the boys I have met here who live in Vancouver and would like to send their love to their families. Jack Rose, George Grant, Don Penny, Lee Speller are the boys from Victoria and Vancouver. Well, my darling, it sure is a long time since I’ve seen you, but I am sure if God spares me we will be together soon. I’ll close now with all my love to the swellest Mother and Dad in the world. Your ever loving son. Jack Goodey.”[936]

As was the case the previous year, the radio broadcasts of messages from Camp 3D were getting through to their intended recipients, and without too much delay. Other broadcasts that mentioned B.C. Signals were picked up as well during May and June, including George Grant’s, with the cheerful opening, “Hello British Columbia, my love and best wishes to my wife Agnes and my Mother at Abbotsford and to all my relatives [and] friends.” He thanked them for the many letters and noted he had received cigarettes from the Tenth Fortress Signals Auxiliary in Vancouver. Messages of love and regards to family members of fellow Signals Jack Rose, Art Robinson, Don Penny, and Johnny Douglas were also included.[937]

The Canadian Government (as indicated in the May 16 covering letter) went to great lengths warning the public not to place “too much credence in Japanese broadcasts.” In a statement reported in the press in June, the Wartime Information Board noted that because the enemy might be releasing the messages for propaganda purposes, “their reliability is, therefore always questionable.” The Board also alerted families to the practice of some scam artists offering to send transcripts of messages for a fee. It pointed out that,

…the official handling of such messages is very thorough, and next of kin are informed of all apparently reliable messages that come through as well as of all other information concerning their prisoner relatives.[938]

Ever since mid-January when the Canadian External Affairs Department had learned about the deaths and injuries at Niigata, government officials had been actively seeking more information through diplomatic channels. In mid-April a series of telegrams between Ottawa and the Canadian High Commissioner’s office in London led to the release of the names of those killed. A Canadian Press story on April 28 referred to the “Typhoon deaths.” About a month later, after next of kin had been officially notified, a list of casualties, including the injured Mel Keyworth and Rolly D’Amours was released to the public.[939]

In August, the Wartime Information Board followed up with more information regarding the reported typhoon deaths at Niigata. A Canadian Press story noted the presence of 125 Canadians at the camp and went on to describe the situation there (reflecting the report given to the Canadian Government by Swiss officials who had visited the camp):

The camp is outside the danger zone, in a health district, and accommodation in wooden huts was considered satisfactory, said the release.

Prisoners have only been allowed to write once since arrival, although theoretically they may send one letter and one postcard every four months. Three consignments of Red Cross parcels have been delivered, and an official source reported that clothing was adequate and the food much improved….

Only fit prisoners work, some of them in machine industries, others in factories and at the docks for which they receive a small remuneration.[940]

It’s not hard to imagine how Rolly D’Amours, Howie Naylor, Walter Jenkins, Mel Keyworth, Ernie Dayton and their fellow Niigata POWs would have reacted to the contents of this government news release. But it reflects the disconnect between the information coming out of Japan and the reality of life in the prison camps.

Another report, this time in reference to Hong Kong, was published in mid-September. The Wartime Information Board referred to Red Cross officials’ assessment that, “the camps are well organized and the treatment of prisoners good.” Red Cross parcels had arrived and would soon be distributed, the officials were told during their visit in August. The report went on:

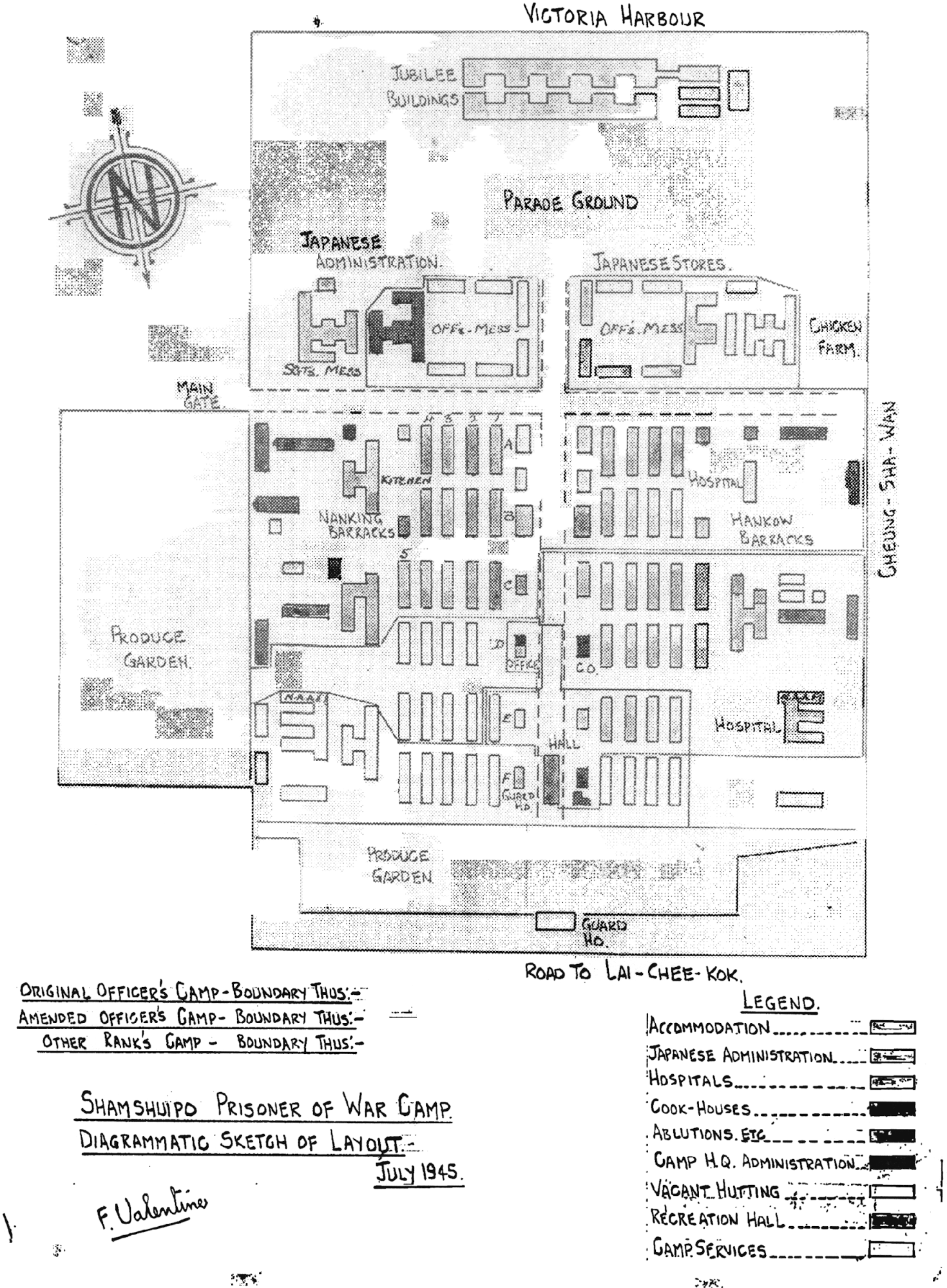

Shamshuipo is a camp composed of brick army barracks, most of which have concrete floors. Large vegetable gardens are under cultivation and there are pig and poultry farms. There also are shoe repair, tailoring and metal workshops.

Each man receives a monthly issue of one bar of toilet soap, one bar of washing soap and one piece of underwear. Towels, toothbrushes, toothpowder and toilet paper are issued at regular intervals. Clothing is reported adequate except for shoes which are poor.

Prisoners are allowed to write one letter or postcard of not more than 50 words for overseas reception, every month, as well as one postcard for local use. The camps have libraries, increased last year by 800 technical and educational books supplied by local relatives. There are sports and recreation facilities, and canteens are open daily for the sale of cigarets, syrup, soya milk powder and daily necessities.

The delegates stated the camps are adequately provided with dressing stations, kitchens, canteens, shower-baths, and lavatories. Shamshuipo has a modern dental clinic, and provides essential medicines and dental supplies.[941]

While such reports might have given some comfort to the men’s families in Canada, it is hard to reconcile the camp description with what the government had learned from confidential reports about conditions at Sham Shui Po.

Sham Shui Po Camp, January, 1944

At lunch, Sgt. Ray Squires, of Victoria, B.C. and Chief Engineer Shottan of England, came with us to share. We had procured a few potatoes, so I had par-boiled them, and then we found a baking pan, and put beans as first layer, spuds, tinned mutton, spuds again, beans and bread crumbs. The bake house heated it for us and together we enjoyed the best meal for months.[942]

Ray Squires, as one of the head medical orderlies, had the opportunity to develop friendships and working relationships outside of the Signal Corps and other Brigade Headquarters units. His diary and a post-war interview contain numerous references to orderlies, medical officers and others he felt close to.[943] But although his hospital responsibilities and medical superiors kept him from work party assignments and drafts to Japan, he was still just one of 248 Canadian non-officer prisoners of war trying to survive the day-to-day challenges at Sham Shui Po.

As noted in confidential reports to the Canadian government, food was low in both quantity and quality, canteen prices for additional items such as salt, garlic and onions were very high (profits, of course, went to the Japanese), there were insufficient quantities of underwear, outerwear and footwear, and dental care and supplies were not good.[944] In spite of all this, morale was apparently improving during the early months of 1944. But sickness and various maladies caused by poor nutrition were still an ongoing problem.[945] In what seems a bit incongruous, all the POWs, except for those in hospital, were ordered to take part in “physical training” exercises. The camp band provided musical accom-paniment for these daily workouts.[946]

On January 24, the bombing raids on Hong Kong which had been absent since late December, began again. Some of the POWs working at Kai Tak airport had been very close to the action, bombs landing only about 150 feet away. A week later another air raid provided quite a show, as recorded by Ray Squires:

Excellent air raid today, 12 bombers escorted by fighters bombed Air field, dog fight took place overhead. 1 Nip plane shot down just outside camp, another pilot bailed out in our view. It crashed with motor full on 1/3 mile away.[947]

On March 1 another raid was recorded:

Lovely air raid last night, three separate alarms starting at 10 P.M. They came over in 5 waves. Horizontal tracers from A[merican] fighters as they tried to find Nip planes. In addition to the full moon was the orange light from the bomb bursts and the yellow parachute flares. There was terrific concussion.[948]

While the American raids gave the men hope that they were not forgotten back home, letters from Canada confirmed that the POWs, if far away geographically, were still in the hearts and minds of their families and friends. Generally, throughout 1944 and into the first months of 1945, mail was being issued at a rate of about fifty letters per week.[949] Considering the large prisoner population, that meant a long time between letters for most. Ray Squires received one on April 22, and then only two more the rest of the year.[950] It was a similar situation regarding outgoing mail. The men were only allowed to send about two 50-word undated cards every three months.[951]

In mid-April, activities in the camp heralded another upcoming draft of POWs to Japan. A group of over 200 men was isolated, given tests and inoculations and prepared for departure.[952] Of the 220 draftees, forty-seven were Canadians, including Signalman Don Beaton.[953] They sailed from Hong Kong on April 29, crowded into a hold below deck on the Naura Maru, a transport ship carrying a cargo of dried fish and soya beans.[954] Don Beaton:

[We] marched on to this freighter and put us down in the hold and they had cages down there….Not enough room in them, you couldn’t stand in them…but nah, you couldn’t all lay down at one time. So it was crowded….

So then they used to let us up every second day, and they’d hose us down with seawater. So we wouldn’t get too lousy, I guess. Heh, too dirty! So after three weeks we landed in Southern Japan. I can’t remember the name of the town, then we were put on a train and sent north of Tokyo.[955]

Don and the rest of the POWs on board ended up in Sendai Camp 2B, about 300 km. northeast of Tokyo. He would spend the rest of the war there, working in the Iwakai coal mine.[956]

Now with more space available, created by the departed draft, Capt. Billings and the other Canadian officers who had been at Argyle Street Camp were moved to Sham Shui Po.[957] They were housed in a separate section of the camp and generally were not allowed contact with prisoners in other sections of the camp.[958] Perhaps this was just as well, because by all reports, the officers were much better off in every way than the rank and file POWs.

By the summer of 1944, the overall health of the men had improved somewhat. Ray Squires, who had been suffering from edema and parasitic worms, was feeling much better. He was even able to enjoy a bit of a celebration for his thirty-second birthday on July 26.

Was called into the ward this morning, sat on a bed and was pounced on by eight huskies, they used a leather belt to good effect. They gave me 7 decks of [cigarettes?] which meant a lot to me.[959]

Although sporting events were a much rarer occurrence than before the drafts to Japan greatly reduced the number of men in camp, there was a baseball game early in July (Canadians-9, Guards-1) and “basketball was in vogue.”[960] Occasional band concerts were still being held and the men were delighted by the Red Cross supplies received in August, which included a gramophone and eighty records. Each hut was able to select the ones they wanted to hear during their scheduled access to the record player.[961] Apparently the food portion of the Red Cross parcels was badly needed, as the quality of rations being distributed at the time was “fit only for worms.”[962] Ray Squires noted in his diary,

Red + food is on its way to us, it is just in time as Pellagra is starting to cause nervous trouble. Breakfast ¾ pint crushed rice. Noon, Melon, rice soup 1 pint. Supper 1 pint melon.[963]

More Red Cross supplies came in at the end of the month, including both food and a quantity of books.[964] Many of the latter were textbooks which were added to the camp library. This allowed interested POWs to pursue studies in a wide variety of topics including astronomy, agriculture, economics, history, maths, psychology, languages and music.[965] For the less academically inclined, the longtime efforts to persuade the Japanese that bingo games were just entertainment, not a form of gambling, finally paid off in September. From then on, afternoon bingo games were one of the primary diversions in camp, often with 200 men participating. The prizes, not surprisingly, were the much sought after cigarettes.[966]

A mid-October air raid was particularly noteworthy because of its intensity.

Good air raid, 28 4-engined bombers over, terrific amount of damage [down]town, much ack ack and M.G. fire in camp. 10 Can[adian] casualties, 3 were within 50 ft of us. Some machines were less than 300 ft from us directly over the camp.[967]

Fortunately, the injuries to the POWs were not serious.

Early in December, there was another significant event – the first hot bath for the men all year. The camp commandant had provided the necessary extra supplies of firewood.[968] Another luxury had been delivered a few days before – Red Cross clothing. Ray Squires wrote:

This is truly a country of contradictions. It is 51° above and everyone is nearly frozen. From the cold damp raw atmosphere at present I am wearing Heavy Limey overcoat, jacket, 2 sweaters, Woolen underwear (thanks to the Red +) kaki [sic] woolen pants and socks with wooden sandals (one strap across the toe) for footwear, in all this I weigh 148.[969]

December was also a month of regular bombing raids on Hong Kong. On Christmas Day, Ray penned the following diary entry:

We have had 8 Air Raids in six days; with American planes just over our heads it is quite easy to distinguish their markings; they are very brave men as they are flying through one hell of pompoms, M.G. and heavy Ack Ack. Last night, Xmas eve, was spoiled, as just at dusk American planes bombing and M.G. and everything. Watched one coming in at 600 ft, about 800 yds away against lowering sun. He ran smack into a heavy Ack Ack. Baled [sic] out but it was depressing. We get a big kick out of Jap planes but the shoe was on the other foot. Certainly the Yanks are recklessly brave and daring.

Highlight of our Xmas day is a 6 oz issue of fresh pork. I must say our present Camp Commandant, S. Major Honda treats us fairly and is a gentleman.[970]

For Ray, his fellow Signalmen Larry Dowling, Tony Grimston and Wally Normand, and the others at Sham Shui Po, fair treatment alone must have seemed a welcome Christmas gift after years of harsh treatment and poor conditions.

Tokyo Camp 3D, May, 1944

In contrast to the situation at some of the other camps in Japan, the commandant at 3D had shown himself to be a reasonable man. After one of the prisoners received a severe beating at the hands of the camp guards, Capt. Reid noted,

I sent a very stiff letter to the camp commandant stating that this form of punishment was simply sadism resulting from uncontrolled rage and requesting the removal of authority for punishment from all the camp staff until the cases had been referred to him personally. The commandant took a serious view of this, reprimanded the Japanese staff very severely and instituted this order.[971]

Although Reid reported that this curtailed harsh physical punishment at 3D, there were still instances of beatings, both in the camp and at the shipyard. Smoking on the job or brewing some tea without permission resulted in punches to the face,[972] and wearing his hat with the earflaps pulled down led to a severe beating for Will Allister.

He [the guard] fell on me like a thunderclap, shouting questions I couldn’t make out. I didn’t know what I had done. When I gave the wrong answers he ripped my hat off and started whipping my face with it. There was a buckle on the end which made a painful weapon. I tried desperately to appease him by answering “hai! (yes)” which roused his anger, then “nai (no)” – which was worse. He was working himself into a fury. He threw down the hat and seized his rifle. He started clubbing me over the head with the butt as he fired questions, demanding answers….

[George] Grant was called up to interpret….Every answer was met with a shriek and a blow….He drew his sword from its scabbard, fired a question at me then turned to Grant and jerked his head at me in a contemptuous gesture that meant “tell the scum.!”

Grant said: “He wants to know how you’d like it if he cut your head off.”

Will’s sarcastic comeback was modified significantly by his fellow Signalman into a more apologetic response, which diffused the situation and probably saved Will’s life in the process.[973]

By the spring of 1944 the number of beatings and deaths in camp had dwindled somewhat, although Section No. 7, which included a number of Signals, was having more than its share of bad luck. Lyle Ellis had died in mid-March, and then less than two months later, his replacement as section leader, Jim Emo, succumbed to pneumonia and cardiac failure.[974] Rene Charron, another Brigade Headquarters N.C.O., was now named to the position. These were well liked and respected men, so it was a tough few weeks for the Section 7 POWs.

The arrival of new batches of mail during May and June were very timely events. Gerry Gerrard was one of the happiest recipients. He got letters on May 2, June 2, and June 12 – a total of five in less than six weeks.[975] Being able to write home was, if not quite as uplifting as receiving a letter, still a rare opportunity to feel a connection with family so far away. On a postcard dated July 11, 1944 (his last communication home while a prisoner of war), Don Penny wrote:

My Dearest Mother, Dad, and Family:

A note to let you know I’m still in good health and hope and pray that you all are the same. Hope Doug is OK wherever he is. Am getting rather homesick as I am thinking about you all the time. Well keep your spirits up and please don’t worry.

Your loving son. Don

The printed card, complete with its series of censor stamps, was eventually postmarked in Vancouver on September 17, 1945.[976]

There was a distribution of Red Cross parcels on May 2, and although only two boxes were allowed for every five men, it was still a red letter day in camp. This particular issue consisted of Union Leader tobacco, toothbrushes, holdalls, bars of soap, tubes of shaving cream, tooth powder, pencils, toilet paper and boot polish.[977]

About this time, the shipyard company started a canteen in the camp, with occasional supplies of green and black tea, curry and pepper.[978] Other available supplies included: coffee, cocoa, fish powder, mustard, malt salt and seaweed salt.[979] The black market was also a regular source of goods. During a particularly active period in July, Signalman Jack Rose (who spoke Japanese) was in the thick of it, receiving supplies on his bunk each morning from one of the guards, and then doing a “booming business” trading the goods for other needed items.[980] Blacky Verreault continued to be an active participant, delivering various supplies he was able to “acquire” to the camp hospital, and following up on specific requests from Capt. Reid for particular medical items.[981]

Generally over the spring and summer there had been a gradual improvement in both camp conditions and the food situation. Many of the POWs showed a slight increase in weight and an improvement in their overall health, prompting Capt Reid to write that sickness at 3D by the autumn of 1944 was “rather uneventful.”[982] Even Blacky Verreault noted that his health was “a lot better than before.”[983] But otherwise, much remained the same. The ever present fleas and mosquitoes feasted on unprotected bodies. The menu was dominated by rice. And the daily routine was just that, routine.

Breakfast at five forty-five and departure for work at twenty to seven. At five to eight, we are at work until five p.m. Quarter to six we return to camp with supper at six. Tanco [roll call] at eight and lights out at nine.[984]

New batches of letters arrived in camp in September and November and although some of the mail was sent from Canada more than a year earlier, a few letters were only about six months old.[985] At the various mail distributions during that period, Don Penny received five letters, Gerry Gerrard got nine,[986] and even Blacky Verreault, who never seemed to hear his name called, received two.

Ah! Ah! Keenan is calling out names! It must be the mail. Something for me?... Let’s listen. He’s getting close! 317 Bingo – 324!! Ah what inebriating joy![987]

Hearing from home wasn’t the only encouraging element in the lives of 3D prisoners that fall. Overhead, B-29 sightings suggested that the Americans were mounting an offensive, and news of the war that was filtering into camp was promising as well. Many of the men started to think seriously about getting back to Canada. Blacky Verreault and Jim Mitchell planned a cross-country motorcycle trip.[988] Others, including Will Allister, started to make bets on when they would be released: “Ten bucks worth of tasty delicatessen meats” if they were free by Christmas.[989] The other news that boosted morale was that men at the nearby headquarters camp had seen the arrival of a large shipment of Red Cross parcels. The timing of distribution and the number of parcels per man were now the dominant topics of conversation.[990] The prospect of nutritious food raised everyone’s spirits, particularly those whose health was a concern – men such as Lee Speller who was suffering through a bout of pneumonia.[991]

In early November, planning began for Christmas. Secret orders were placed for materials that could be scrounged or stolen from the shipyard and turned into decorations.[992] Such activities made for a pleasant diversion from the day-to-day work and prison camp routines. November also saw the beginning of frequent air raid alarms. At the shipyard, the men were crowded into the mess hall to wait for the all clear signal. When the alarms occurred in camp, all the POWs were forced to crawl into holes that had been dug out for air raid shelters behind the huts.[993]

A major change at 3D took place at the end of November. For over a year a new hut had been under construction, and on the 29th everyone made the move to their new quarters.[994] Unlike the previous arrangement, this new hut accommodated all the prisoners under one roof, with double-decker bunks. Part of one of the old huts was set up as a hospital and medical inspection room, with another part used as a shoe shop.[995]

Another change in the camp took place on December 10. Twenty-three men, including three Signals, were transferred to Omori, the Tokyo area headquarters camp. The next day, an additional seventy-three were sent to Shinagawa, site of the main POW hospital for the Tokyo area.[996] Blacky Verreault, one of his section mates, Jim Mitchell, and Bob Acton were among those sent to Omori, while Johnny Douglas went to Shinagawa.[997] The move, taking these men away from long-time prison camp buddies, their familiar routines, and not insignificantly, the extensive Christmas preparations at 3D, was very upsetting.[998] Although they were told the transfers were for medical reasons and when their health improved they would be returned to 3D, the men knew there were few certainties in the life of a Japanese POW.

Omori Camp, December, 1944

The three Signals’ new home was located on a small island in Tokyo Bay, only about 50 metres from shore. There were the usual wooden barracks, kitchen, latrines, and guard house, plus a leather shop. There were also a number of office buildings and storage huts related to the “headquarters” status of the camp.[999] The Canadians joined a diverse group of American, British, Australian and Norwegian prisoners representing army, navy and air force units. One of the biggest changes for the men from 3D was the strict discipline and many new rules and regulations. One of these was the order that all prisoners, including officers, must salute every Japanese, not just soldiers. Failure to do so would result in severe punishment, usually administered by the Japanese N.C.O. (Watanabe, or “the Bird” as he was known) who ran the camp.[1000] Blacky Verreault wrote,

There’s terror in the barracks. It’s a Japanese sergeant who has great authority in the running of this camp. He is much feared. He apparently beats up prisoners that have the misfortune of displeasing him.[1001]

Unfortunately for Bob Acton, he was one of the many who found himself the object of “the Bird’s” displeasure. Bob had been beaten and ordered to stand outside his hut for the crime of wearing a Red Cross sweater. The sergeant had given him “a few bashes” and told him to stay there.

Well it was about nine o’clock at night. I’d been standing there and another sergeant came out to take roll call and I asked him if I could go to my hut and he said yes. And the boys had saved me supper so I had that and about half an hour later some Jap comes in and says, “Sgt. Watanabe want Acton.” So I got up and got dressed and I went over to his hut and into his office and he started bashing me and I couldn’t understand what the hell was wrong. As I said, his English wasn’t very good; at last he got out that he wanted me to take my wooden clogs off – they take their shoes off any time they go inside any accommodation. So that got in my head at last and then he started asking me questions and all of a sudden he drew his sword out of its scabbard and he stuck the point in my throat and he started pushing me – putting pressure on me – back to the wall. In my mind I kept thinking he’d get shit if he killed me, but anyway he says, “you not answer the question ‘karray’. Now ‘karray’ is orderly officer, and every time I’d say, “yes sir, I don’t answer the question ‘karray’” I got another bash with his fist or his scabbard that the sword came in. And that went on for half an hour, and then something struck me. They can’t say “L”…so I switched my “L” – “I don’t answer the question clearly.” And his faced beamed like that. He said, “Have you had your supper?” I said “Yes sir.”[1002]

Such was the arbitrary and confusing reality of punishment at the hands of “the Bird.”

Additional consequences were to follow, as recorded in Blacky Verreault’s diary.

The Bobby Acton incident upset “the bird” and to punish the twenty-five Canadians he put us on banjo fatigue, that is to drain the toilets with buckets and walk our odorous load outside the camp to the site of the future garden. Until further orders, this is our job till other victims draw “the bird’s” irate attention.[1003]

Two other differences between Omori and 3D were the work regime and the food situation. Many of the prisoners were assigned small duties around the camp or to light work parties. The men also received full rations and were unofficially allowed to steal or acquire other food supplies.[1004] This was particularly the case for the men who worked outside the camp. Those on the warehouse gang were able to steal sugar; others brought in tobacco and rice. With all the ration supplements available, the general health of the men was much better than at 3D.[1005] Blacky Verreault wrote:

Generally, the inmates of this camp are in admirable physical condition and during our physical, the doctor had a look of disgust, contemplating our bony torsos and pale skin….This afternoon we were assigned to the leather shop, a cold and unpleasant place. There’s nothing to do and we have to look busy. There’s nothing more tiring than that. I miss my section. Here, I only have Mitchell, the others, I know by sight only and have no interest in them. Mitchell, like me, is sick of the place.[1006]

Even if they were “sick of the place,” life at Omori during December, 1944 had its advantages. The light work regime allowed Blacky time to mend his clothes and sew a variety of items for himself and Jim Mitchell, including slippers, gloves, and bags for their dishes. The extras brought into camp by men on work parties unloading food supplies (including a memorable two-foot long salmon) meant for regular full bellies and a substantial weight gain for the Canadians who had come from 3D. Blacky also discovered, to his great pleasure, a choir being formed in preparation for Christmas – a natural outlet for his musical talents.[1007]

Christmas brought not only the choir concert, but the much anticipated distribution of Red Cross parcels.

Christmas! It’s gone but what a wonderful day it was! I had a full stomach with such delicacies as chocolate, jam, meat, milk, coffee, etc! The concert was a success and the Yanks had the courtesy not to bomb us. High mass and communion were held before breakfast. Around noon, they came to fetch me to sing during dinner for “the bird” and a few high ranking American and English officers. I sang in five languages: Oh Holy Night in French, Sweetest Kojohostki in Japanese and Volga Boatman in Russian. “The bird” congratulated me on my warm voice and my ability to sing in so many languages.[1008]

The Christmas spirit, however, was short-lived. A few days later Sgt. Watanabe reacted to some perceived negligence by lining everyone up and beating them with a stick. The only Canadian spared punishment was Blacky Verreault.[1009]

Tokyo Camp 3D, Christmas, 1944

Back in Kawasaki, the men of 3D had continued their preparations for decorating the new barracks. Will Allister’s section was particularly creative: paper roses in tin vases, pipes covered with coloured paper to form candles, wreaths woven from old straw rain capes, kitchen-ash bleached bedsheets for tablecloths, paper snowflakes for the windows.[1010] Capt. Reid was impressed.

Christmas again this year was very successful – the men made very amazing decorations, with streamers and fireplaces and santa clauses and so on – really amazing and all made out of scraps gathered from here and there. In the morning we had white rice, a great delicacy and soup with leeks and carrots and twenty kilograms of meat. The leeks to flavour it were a wonderful delicacy. At noon each man had one loaf of bread with some miso paste. Leek soup, Christmas pudding – two parts flour to one of sugar. For supper fish, one hundred and twenty-five grams per man, white rice, soya soup, and sweet beans with sugar and Christmas pudding. Red Cross parcels arrived in the camp and were issued one per man on Christmas eve. The Church Service and Christmas carols on Christmas Eve, a concert by the orchestra and the Japanese again came in Christmas afternoon and took photos.[1011]

In the midst of the visual merriment, there was also a reminder of their situation as POWs. On the wall across the aisle from one large wreath, the men had hung an imitation scroll, hand-lettered by Will Allister:

We said: “By Xmas ‘42

We know the war will all be through.”

We said: “By Xmas ‘43

We know that we will all be free.”

We said: “By Xmas ‘44

We know there will be war no more.”

But now? “By Xmas ‘45

I hope to hell we’re still alive.”[1012]

If only they could have known that a year later they would be spending Christmas back home in Canada.

Sham Shui Po Camp

Chapter 6: Prisoners of War - 1944 - Notes

[863] Beaton, C. Magill interview

[864] It’s not known whether Kurluk went directly to Oeyama or Narumi, although it appears he was eventually at the latter camp. Mansell website.

[865] D’Amours, Chapter 11: 4

[866] Leslie (Keyworth) Henderson, p.c.

[867] Atkinson: 31, HKVCA website

[868] CWM, Stewart 58A 1 214.18; NAC Reel C-5342: Telegram May 19, 1944 to External Affairs, Ottawa

[869] Guiard, Jan. 2, 1944

[870] Forsyth: 44

[871] NAC Reel C-5342, Telegram Jan. 19, 1944 to External Affairs, Ottawa

[872] e.g., Forsyth, Guiard

[873] Roland: 235

[874] Cambon: 71

[875] Jenkins, C. Roland interview: 20

[876] CWM, Stewart 58A 1 214.20; .21; .22

[877] Forsyth: 44

[878] Roland: 236

[879] Cambon: 71

[880] Forsyth: 51

[881] Guiard: Jan. 25, 1944

[882] Cambon: 74

[883] Jenkins, C. Roland interview: 31

[884] D’Amours, Chapter 11: 5

[885] Cambon: 73

[886] Forsyth: 45-46

[887] Cambon: 72

[888] CWM, Stewart 58A 1 214.17; 58A 1 214.22

[889] Forsyth: 46-47

[890] Roland: 243

[891] NAC Reel C-5342; External Affairs, Ottawa, June 29, 1944

[892] CWM, Stewart 58A 1 214.22

[893] Roland: 241-242

[894] Forsyth: 51

[895] Forsyth, VAC website, Canada Remembers

[896] CWM, Stewart 58A 1 214.25

[897] Naylor family files

[898] Cambon: 78

[899] Forsyth: 57

[900] CWM, Stewart 58A 1 214.26; 27; 28; 29

[901] Roland: 247

[902] CWM, Stewart 58A 1 214.17

[903] Forsyth: 60-61

[904] Cambon: 78

[905] Reid: 113

[906] Penny family files

[907] Bérard: 139

[908] Verreault: 126

[909] Allister: 162

[910] Reid: 114

[911] Acton interview, Daily Colonist, Oct. 6, 1945

[912] Gerrard, p.c.

[913] MacDonell: 109

[914] Speller, C. Roland interview: 23

[915] Reid: 115

[916] Gerrard, author interview

[917] Reid: 119, 123

[918] Reid: 115

[919] Bérard: 153

[920] Gerrard, p.c.

[921] July 20, 1942, Penny family files

[922] Allister: 180

[923] Verreault: 127

[924] Reid: 126

[925] Reid: 132

[926] Gerrard, author interview

[927] Speller, C. Roland interview: 24

[928] Verreault: 172

[929] Allister: 134ff; 176-177

[930] Reid: 130

[931] Allister: 168

[932] Reid: 129

[933] Penny family files

[934] Reid: 134

[935] Broadcast transcript, Penny family files

[936] ibid.

[937] ibid.

[938] Globe and Mail, June 13, 1944

[939] NAC, Reel C-5342

[940] Globe and Mail, Aug. 23, 1944

[941] Globe and Mail, Sept. 16, 1944

[942] Laite, Jan. 2, 1944

[943] Squires, Diary and C. Roland interview

[944] NAC, Reel C-5342, Ext. Affairs, Jan. 25, 1944

[945] Squires: 17

[946] Laite: Jan. 25, 1944

[947] Squires: 17

[948] Squires: 18

[949] DHH 593.D7

[950] Squires: 18-20

[951] DHH 593. D7

[952] Roland: 214

[953] DHH 593. D10

[954] Roland: 214

[955] Beaton, C. Magill interview

[956] Roland: 275

[957] DHH 593. D7

[958] Laite, May 11, 1944

[959] Squires: 18-19

[960] Laite, July 2; 23, 1944

[961] DHH 593. D7

[962] Laite, Aug. 18, 1944

[963] Squires: 19

[964] Laite, Aug. 31, 1944

[965] DHH 593. D7

[966] ibid.

[967] Squires: 19

[968] Laite, Dec. 10, 1944

[969] Squires: 20

[970] Squires: 21

[971] Reid: 134

[972] Verreault: 129

[973] Allister: 177

[974] Reid: 135

[975] Gerrard, p.c.

[976] Penny family files

[977] Penny notebook

[978] Reid: 145

[979] Penny notebook

[980] Verreault: 128

[981] Verreault: 144

[982] Reid: 148-149

[983] Verreault: 132

[984] Verreault: 133

[985] Don Penny letters, Penny family files

[986] Gerrard, p.c.

[987] Verreault: 175

[988] Verreault: 154

[989] Allister: 197

[990] Allister: 207; Verreault: 161

[991] Verreault: 165

[992] Allister: 208; Verreault: 172

[993] Verreault: 174

[994] Verreault: 186

[995] Reid: 150

[996] ibid.

[997] Penny notebook

[998] Verreault: 193

[999] Roland: 280

[1000] ibid.

[1001] Verreault: 195

[1002] Acton, author interview

[1003] Verreault: 201

[1004] Reid: 151

[1005] Roland: 284-285

[1006] Verreault: 194

[1007] Verreault: 194-202

[1008] Verreault: 203

[1009] Verreault: 204

[1010] Allister: 209-219

[1011] Reid: 151-152

[1012] Allister: 219