Chapter 4

Prisoners of War - The First Year

The Jap soldiers came up there and then they told us to go to a field that’s in the city – I don’t know what it was for, it wasn’t very big – and first they said to us, “smash your guns,” so we bent the barrels by hitting the cement with them. Then we went to this place and they had built a stage and the Jap Commander came up and spoke Japanese and the interpreter said, “If I had my way I would line you all up and shoot you dead, but headquarters in Tokyo won’t let me do that.” So right away we thought it’s going to be a tough go. (Bob Acton) [357]

…we all got lined up and they [Japanese soldiers] just went up and down slapping, some of them kicking, and some of them ripping off their glasses and tramping them on the ground. A lot of them were stealing the watches and rings off the guys, and wallets. … And there was nothing you could do to stop them. If you tried stopping them you just got it worse. (Lee Speller) [358]

Confusion; uncertainty; fear. How else to describe what was going through the minds of these soldiers who were now “Prisoners of War”? As was the case during the battle, the men of the Signal Corps were still spread out around the colony. Most of the group had been in the West Brigade area of the Island and were now held at Sham Shui Po on the mainland. But no one had any way of knowing the whereabouts or condition of their comrades who weren’t there with them. Ron Routledge and possibly a few others had ended up at North Point Camp, which overlooked the harbour across from Kowloon. Ray Squires was at War Memorial Hospital on the Island near the Peak. James Horvath was at Bowen Road Hospital, critically wounded; he would not survive the first week of captivity. Also at Bowen Road were Will Allister, with a severe case of dysentery, and Captain Billings, now almost fully recovered from his earlier wounds.

Sham Shui Po Camp, Early January, 1942

What remains of my Brigade Headquarters gang has been moved to a hut with no windows or doors left. (Blacky Verreault) [359]

In contrast to the fine accommodation that the Signals had been treated to when they arrived at Sham Shui Po six weeks before, the whole place, including the Jubilee Building, was a complete shambles. After the Canadians left, the Chinese had systematically looted the camp. All the windows and doors had been taken. Every bit of wood that could be ripped up was gone, even the toilet seats, and all the faucets and pipes had been torn out of the washrooms.[360] Now, into the chaos of the destroyed camp the Japanese had imprisoned 5000 captured soldiers.[361] The weather was cold, there were no stoves for heat or cooking, and many of the men were sick or injured. Canadian Medical Officer, Captain John Reid was there:

During the time I was dressing the wounds of the men and some had picked up dysentery and stuff like that….

Practically no food, and everybody was just starving to death. You would lie around unable to sleep because you were so hungry.[362]

The first few days were spent just trying to clean up the place and get things organized. The Japanese had indicated they had no intention of bringing any order to the situation, so the senior officers met and drew up plans, “for each service to do what they could.”[363] The Jubilee Building was set aside for officers and senior NCOs[364]and the Canadian Brigade Headquarters was assigned to one of the huts.

After a few days a Japanese truck arrived at the fence surrounding the camp and dropped off a load of old gasoline barrels and about twenty or thirty large bags of rice – the POWs’ ration for the next ten days. The barrels were to be used as pots to cook the rice and the result was an unappetizing goop that smelled of gasoline.[365] No wonder the men were constantly hungry! This led to a consistent topic of conversation throughout the camp: Food. They thought about it, dreamt about it, and wrote about it.

…once Jenkins struck an attitude and declaimed:

You may live without books,

What is knowledge but grieving?

You may live without hope,

What is hope but deceiving?

You may live without love –

What is passion but pining?

But where is the man who can live without dining?[366]

His hut mates may have been a bit surprised to hear such lines of verse from Walt Jenkins, an ex-Winnipeg Blue Bomber football player who hadn’t yet reached his twenty-first birthday.

Blacky Verreault’s diary for the first three weeks of January contains numerous references to food (or the lack of it) and how hungry he was:

Every day I get weaker. Hunger! I really know what it means now.

Every night, I dream of an enormous steak with creamy whipped potatoes, served with my mother’s delicious yellow chow chow and heavily buttered white bread: all of this washed down with a delicious cup of coffee.(January 7)

Boy will I appreciate my home cooked meals: How succulent they’ll be! I can’t wait! I think about it continuously and my stomach is in constant turmoil. (January 10)

I woke up this morning, my stomach empty again. I must have a degree of endurance because many have not endured. The hospital is filling up. The doctor has stated that unless our diet improves we’ll be gone from this world in three months. (January 13)

Our succulent daily meal is over and the sun is slowly setting on the horizon….We are better fed in solitary confinement in Canada. I spend my days occupying my time as best I can, I play solitaire for a while: I light my pipe: I argue with my comrades on the advantages of Montreal over their own home town. It helps but I do believe that whether from the east or west, we are all brother Canadians. (January 14)

The guys are out of cigarettes and there’s a race on for who can pick up the most butts. When I arrived in Hong Kong from Canada, I had already lost 16 pounds. Since our captivity, each man has lost an average of 20 pounds. This means in my case, 16 plus 20 – 36 lbs. My weight before was 184 now down to 148. (January 15)

One of my comrades can’t stand rice and will only eat it when the kitchen mixes some peas with it. Since this is a rare occurrence, he’s now only a shadow of himself. He’s so thin that he’s scary. (January 19)[367]

Not surprisingly given the poor diet and unsanitary conditions, the health of the soldiers, including men from the Signal Corps, began to deteriorate. In the small hut set aside as a “hospital” Wes White was treated for dysentery and Wally Normand was in with a fever and diarrhea during the first month of captivity.[368]

North Point Camp, Early January, 1942

Housing, billets that we were assigned to were in a filthy condition and well, it was just generally not a good sight. The buildings were in poor repair, very poor repair. There was insects and vermin. (Ron Routledge)[369]

North Point Camp had originally been built in 1939 by the Hong Kong government to house Chinese refugees. It had been badly damaged during the battle and some of the buildings had been burned and looted. The Japanese had stabled their horses there and large piles of manure and garbage attracted huge numbers of flies and other insects.[370] The sleeping huts had few doors or windows and offered little protection from the weather. For the first few weeks, sanitary arrangements were totally inadequate; there was no running water and latrines had to be improvised along the seawall.[371] Rifleman Ken Cambon was one of the prisoners at North Point. He later wrote:

The first month was tough as chaos reigned. There was no water in the camp. It had to be brought in by truck and the delivery of any food was unpredictable. We had nothing to eat for the first two days, and the situation looked grim.

Accommodation was no better, as at first we had all the British and Indian troops as well as the Canadians. We were packed about 200 men into a hut designed to hold perhaps 30 refugees. There was no glass in the windows and in some huts large holes in the roof. Most of us had no blankets and the concrete floor was no Beauty Rest Mattress. Hong Kong can be damp and cold at that time of year.[372]

Sham Shui Po Camp, January 12, 1942

My greatest wish is to be allowed to send a telegram home. My father must be terribly worried. He may even think I’m dead. (Blacky Verreault)[373]

If food was uppermost in the minds of the POWs, thoughts of home were certainly close behind.

Canada, Late December, 1941

Back in Canada there was definitely worry; and not just about what had happened to the Canadian soldiers. News reports of the battle had been heavily censored and it wasn’t until after the Christmas Day surrender that the government officially released the names of the men who were there. For some families, this was the first confirmation they had that their sons or husbands were actually in Hong Kong.

Japanese aggression in the Pacific was beginning to raise fears of an attack on Canada’s west coast. Rumours of imminent invasion and possible subversive activity by Japanese residents prompted plans for sending troops to British Columbia and the evacuation of Vancouver Island. Now that newspapers throughout B.C. were publishing the names of their local “heroes” at Hong Kong (including many of the Signals), there were fears of an anti-Japanese backlash. So much so, that the Cabinet War Committee in Ottawa was advised that local police and other authorities in B.C. were less concerned about subversive activity than they were about serious anti-Japanese outbreaks of violence.[374] At the same time, efforts were underway to find out information about the fate of our soldiers. On December 26, Prime Minister King said that they were trying to get any reports as quickly as possible, but,

…it may be some time before accurate news of the fate of our men will be available…. The Government shares the anxiety of the families of our soldiers, and no opportunity of relieving it quickly will be overlooked.[375]

The next day, plans were put in place by the Canadian Red Cross to obtain information about prisoners and casualties through the International Red Cross in Geneva, Switzerland. An official noted that Japan was not a signatory to the Geneva Convention regarding prisoners of war, so delays were to be expected.[376] Illustrating the fragmentary nature of information getting to Ottawa was the first post-surrender casualty list issued on December 31 by the Defence Department – only eleven names listed and no R.C.C.S. men included.[377] But the effort continued on many fronts. The Department of External Affairs had begun to exchange messages with diplomats and agencies around the world. National Defence was also very active, particularly working with British officials to elicit whatever bits and pieces of information they were getting from their contacts in China.

On January 14, 1942, the Defence Department sent out the first of what would be a continuing series of letters establishing contact with the next-of-kin of Canadian troops who fought at Hong Kong.

I recognize fully how anxious you are regarding the welfare of your son, the soldier marginally noted, who proceeded to Hong Kong with the Canadian Force.

I regret no information other than what has been published is yet available regarding individual members of the Canadian Forces who participated in the action at Hong Kong. I may say that in the case of British personnel the War Office advise us that until other information is received they have adopted the procedure of posting the soldier as Missing. However, the Canadian Government is loath to adopt this course for the present until further efforts have been exhausted and every endeavour is being made through all possible channels to obtain definite information.

In this connection, our Government has the direct assistance of both the Argentine and Swiss Governments, which respectively represent Canadian interests in Japan and in Occupied China. We also have the co-operation of the United Kingdom Government and the War Office, who are of course profoundly interested on behalf of both British and Canadian troops. We have assurance that all these authorities are putting forth every effort to hasten the receipt of information. We have also been in touch with the British Embassy in Washington, and efforts are being made as well by the International Red Cross.

You may rest assured that on receipt of any particulars respecting the welfare of your son you will be advised immediately by telegram, as it is fully realized that suspense may cause even greater distress than a full knowledge of the facts, whatever they may be.

Yours truly,

(W.E.L. Coleman),

Lieut-Colonel,

Officer i/c Records

For Adjutant-General[378]

Appended to the letter was a notice that word had just been received that the Japanese had established a Prisoners of War Bureau and information was to be exchanged through the Red Cross. It indicated that the Canadian High Commissioner in London, the Hon. Vincent Massey, had requested that the Red Cross representative in Tokyo communicate directly with his counterpart in Canada, thus hastening “the receipt of anxiously awaited information.”[379] On the same day the letter was sent, Canadian Press was reporting that new information coming out of Britain suggested that, “Canadian casualties in Hong Kong are feared to have been heavy.” The injury of Captain Bush, Royal Canadian Army Service Corps, was reported, but no other details were provided.[380] Another report a week later again indicated that Canadian casualties were expected to be heavy. It also noted that the Argentine Embassy in Tokyo was representing Canada’s interests and might be able to provide information about the condition of Canadian soldiers.[381] In the midst of all the anxiety and tension about the fate of Canada’s troops in Hong Kong, the government also was aware of increasing anti-Japanese sentiment, particularly on the west coast. A news release was issued warning against any action or demonstrations against members of the Japanese community, “which might give Japan an excuse to mistreat Canadians in its hands.”[382]

Hong Kong, Late January, 1942

Back in Hong Kong, it didn’t appear that the Japanese were looking for any excuse coming from Canada.

I was in Headquarters and I was right there with the officers when the shit hit the fan there at Sham Shui Po. And the British said to the Japanese officer…, “we need certain things,” and he said, “Lookit, see that truck over there? In the back is a machine gun pointing right at you, so if you don’t like what they’re doing, you can take the machine gun.” We moved to North Point the next day.(Jim Mitchell)[383]

On Friday, January 23, twenty-three Canadian officers and 590 O.R.s were transferred from Sham Shui Po to North Point Camp, now bringing the total there to about 1500 Canadians.[384]

North Point Camp, January 25, 1942

In the few weeks since arriving at North Point, the original prisoners had been actively fixing up the place. Scrounging parties had brought in all kinds of supplies and, at least for the moment, the food situation was much better. The move from Sham Shui Po made Blacky Verreault’s spirits soar.

Our situation has improved truly remarkably. La! La! What a change. We just changed camp. This time, Canadians are all together and the meals are marvelous. It’s like a dream. Breakfast consists of porridge with sirup [sic], bread, butter, tea with milk and sugar. Dinner; cornbeef, biscuits, butter, tea and sometimes cheese. I almost fainted when I presented my plate and it was filled with beef stew. The[y]underfed us in the other camp because of the British. Now that we’re all Canadians together we eat like kings. We are all together in a hut that we repaired, I mean the same group as on the ship.[385]

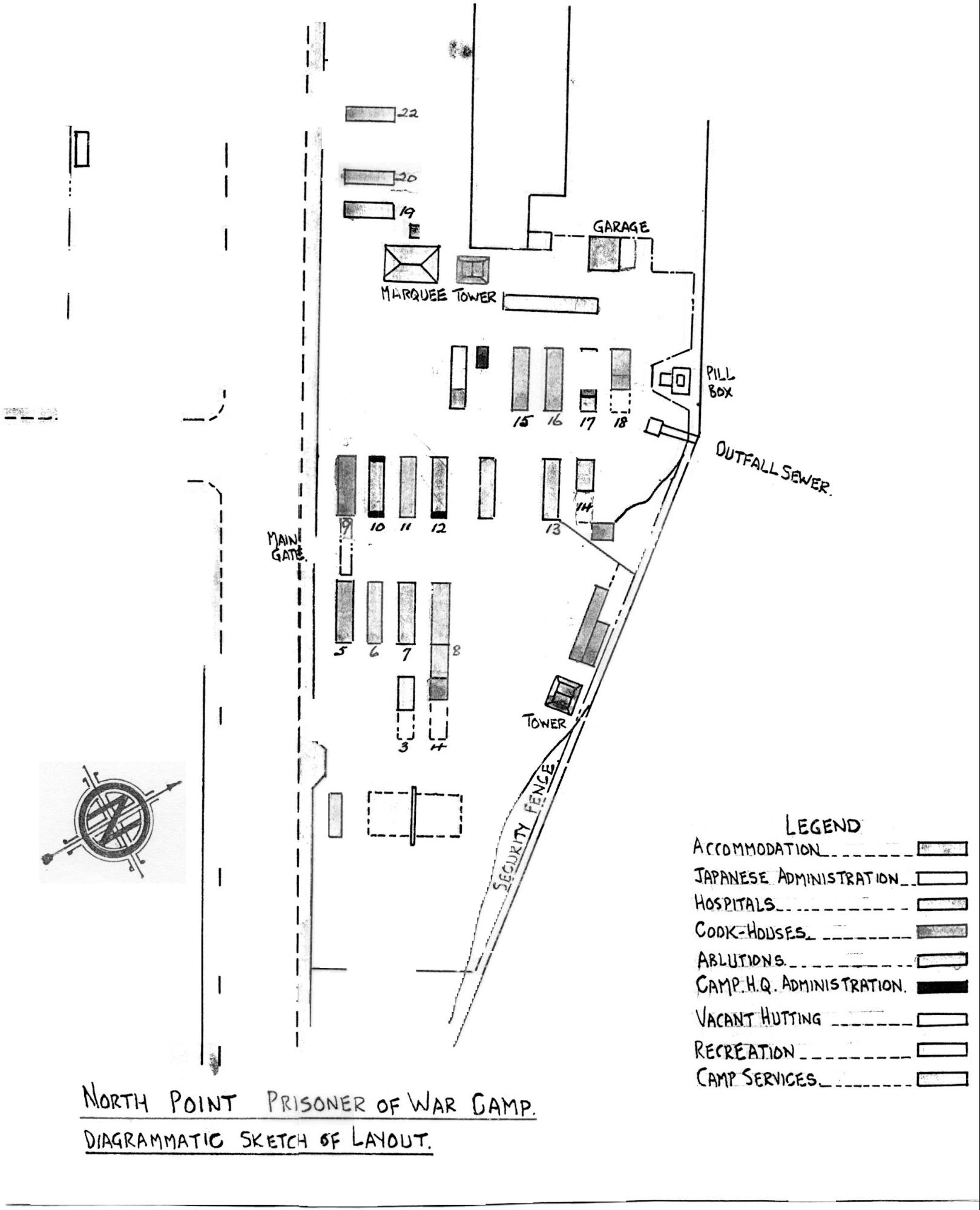

Blacky’s euphoria would be short-lived. After all, they were prisoners of war, captives in an overcrowded, unsanitary, battle-damaged refugee camp. Located on a narrow strip of land with Hong Kong harbour along one side, the camp was a collection of about twenty huts surrounded by a high, wire fence. There were guard towers, lights, and sentries posted inside the wire.[386] Gerry Gerrard, who had just turned twenty a few days before the move to North Point, recalled, “All the Headquarters were in one hut. There was one shorter hut that had the end blown off; that’s the one we were in.”[387] The sleeping huts were one storey wooden structures 120 feet by 18 feet with concrete floors. Access was from four doorways and light came from window openings along each wall.[388]

When Will Allister arrived in late January from his stay in Bowen Road Hospital, he was initially assigned to a hut occupied by men of the Royal Rifles. But soon he was transferred to the Brigade Headquarters building and was now back with familiar faces.

Guards paced to and fro beside our hut near the barbed wire fence. Windows and doors, shattered or looted, were crudely boarded up against the cold and rain. The double bunks were infested with bed bugs that sucked our blood by night while lice lived on our unwashed bodies. For light in the bleak evenings we rigged up small tin cans with a lighted string soaked in kerosene. There was no heat in our undernourished bodies and we lay shivering in the cold January nights – huddled together for a glimmer, an exchange of warmth, staring into the tiny flame before us, absorbed in its imaginary heat as though it were a roaring fireplace. If there was a cigarette, four or five men shared it, then kept the butt….

Time to sleep. Out went the miserable little wick with the three of us huddled close in the darkness. I in the middle being weakest, Blacky on the outside warding off the gusts of wind blowing through the cracks. Tony on the right. Each alone with his thoughts and his growling empty stomach.[389]

Although the buildings at North Point were wired for electricity, battle damage and looting had left this system in poor shape. Captain Billings was put in charge of getting the electricity up and running in the huts. He assigned Gerry Gerrard and a soldier from the Army Service Corps to work on the repairs. Gerry recalled that Padre Laite, one of the Grenadier chaplains, asked him to install a light in a small hut housing the sick. Lying on a stretcher on the dirt floor was a soldier with the hiccups – they were constant and the doctors weren’t able to stop them. “We installed a light,” said Gerry, “but he died a few days later.”[390]

The toilets were built over the water here and you were crapping practically on the Chinese coolies working on the water getting crabs and things.(Bob Acton)[391]

Before the water system was repaired at North Point, temporary latrines were set up along the sea wall. But the increasing number of dysentery cases meant that even with newly constructed latrines, squatting along the sea wall, holding onto a wire fence was still the only alternative for many of the prisoners.[392] Eventually, four washing rooms were set up, with a total of twenty water taps and sixteen showers (cold water only).

The lack of water, overcrowding, and use of the sleeping huts for eating (no mess rooms were available) meant that cleanliness was a constant problem. There were few brooms or other cleaning utensils, but the huts were washed out every week.[393] Bedbugs, lice, rats, cockroaches, and other insects were a constant irritation.

Bugs and parasites of many kinds populated North Point Camp. The flies swarm through every man’s recollections. One veteran had the smothering, nauseating sensation of almost breathing flies. They settled on every forkful of food before it could reach the mouth. Men spent their days swatting flies….

Ultimately, fly-catching was ordered by the Japanese,…This began as early as 6 February 1942, when it was ordered that everyone must kill his quota of flies each day.[394]

As an incentive, the Japanese offered prizes of cigarettes for the flies collected.

They counted the flies, or made the POWs count them at first; then they decided that they would weigh them. The prisoners, predictably, started tying little weights to the flies’ feet; some men bred flies in their mess tins in order to get cigarettes. Eventually the Japanese discovered this scam. The offer of cigarettes ended.[395]

The food situation that had seemed so much better at Sham Shui Po quickly deteriorated. On February 12 the rice rations were reduced in half and supplemented by two pieces of bread.[396] On February 25, Blacky Verreault wrote:

Two months on rice and we endure. Human nature has tremendous resilience; our rations have been cut again! Here’s our menu for today.

Breakfast: lightly sweetened rice, enough to fill a saucer.

Dinner: two slices of bread and a cup of tea.

Supper: same as breakfast but with a sauce that God only knows what the ingredients are.[397]

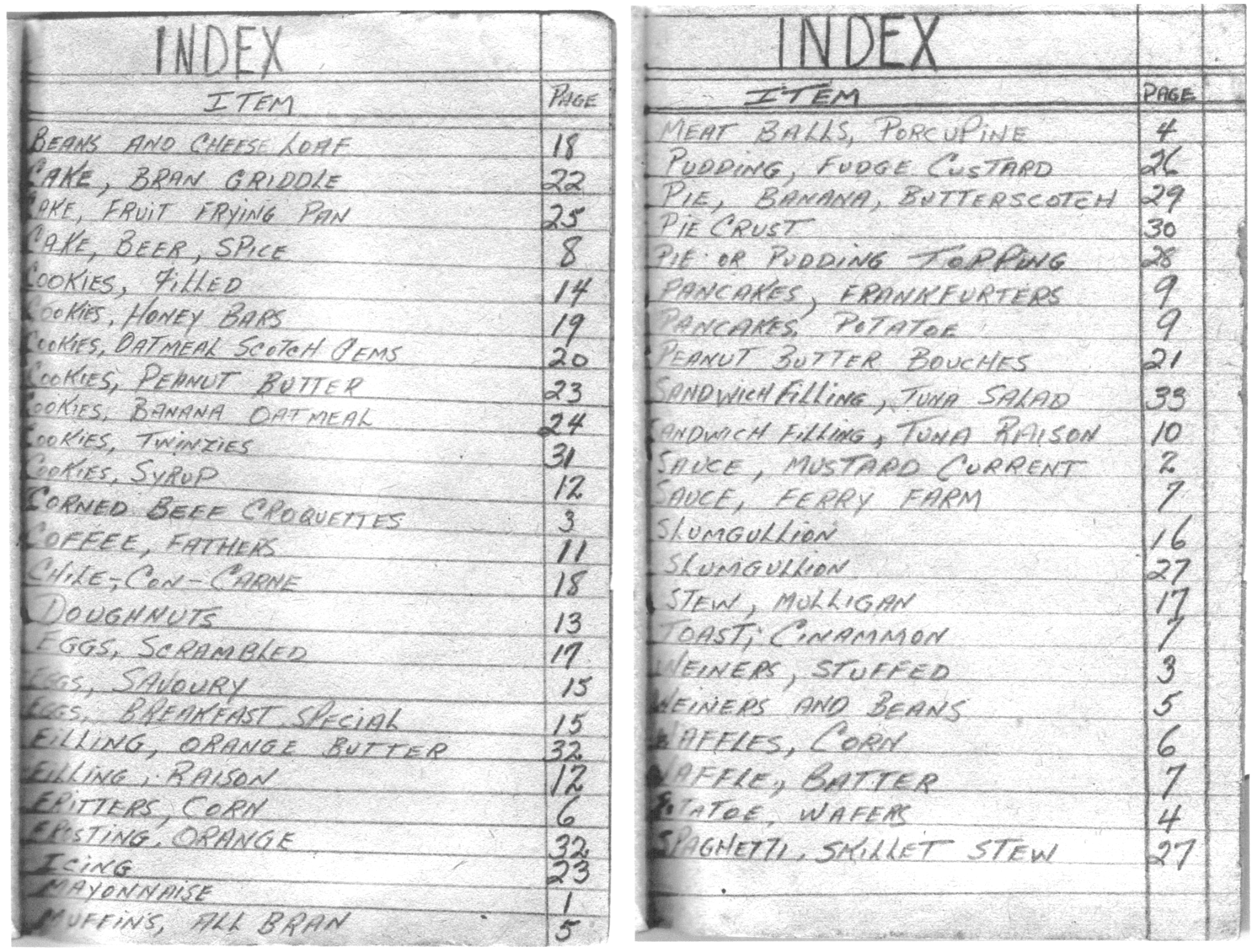

Still hungry after each meal, the men, understandably, thought often about food. They talked about it, apparently for hours every day.[398] Discussing recipes became a popular pastime. Will Allister wrote about his reaction:

To watch the cautious trading and exchanging of recipes in the hut was to sense the creeping madness in the air. Men had taken to compiling whole recipe books. They would even trade some article of value for an enticing new recipe. They would venture outdoors braving the cruel wind and rain to meet another collector and work out an exchange, returning shivering and victorious with eyes alight.[399]

Within the camp, different men sought a variety of diversions from their difficult situation. Don Penny was a member of the recipe group. A small, blue covered notebook was one of his war-time mementoes.[400] In it he recorded over thirty recipes, instructions for various drinks, and a list of food-related “Things to try.” The recipe index on the last two pages lists a wide range of items, from the mundane (Pie Crust; Toast, Cinnamon; Wieners and Beans) to the more elaborate (Pudding, Fudge Custard; Corned Beef Croquettes; Slumgullion; Banana Butterscotch Pie). Also in the notebook Don wrote out, “My first meal that I will buy,” his contribution to another common topic of conversation.

Pancakes or griddle cakes with a fried egg (done well on both sides) in between. Pork sausages put around the edge of the plate and either Rogers Golden Syrup or maple syrup poured over the top – 2 cups of good coffee.

He then added a full day menu plus a “Midnight Lunch:”

BREAKFAST

4 Griddle Cakes, Two fried eggs done on both sides, Rogers Golden Syrup, butter, 5 Pork sausages, toast & strawberry jam, coffee.

LUNCH

3 hot pork sandwiches, Thick brown gravy, peas, carrots, potatoes – raison [sic] or mince pie, tea (apple sauce with pork)

SUPPER

Hot roast chicken, sweet potatoes, peas, carrots, thick brown gravy over vegetables, cranberry sauce. Lemon meringue or pumpkin pie and coffee

MIDNIGHT LUNCH

Thin cheese wafers, pimento cheese, Spanish onions and milk-sweet donuts.

Besides prompting day dreams and discussions, poor diet caused a serious decline in the weight and general health of the prisoners. Medical Officer Capt. John Reid reported during that time there were 200-300 men on sick parade each day. Skin troubles and dysentery were common.[401] Two Signals, Jack Rose and Wally Normand were both in the camp hospital during February suffering from dysentery.[402]

Once the fighting is over, everybody reassumes his normal behaviour and that’s not pretty. The officers become snooty again while the men return to their disagreeable selves. It’s true that it’s been two months since I’ve been able to unwind on somebody and our circumstances don’t ease my tense state towards the others. (Blacky Verreault)[403]

Hunger and poor conditions also meant that many of the men were in less than ideal mental condition. Disagreements, frustrations, resentments – things that under better circumstances would have been passed over – all contributed to a general feeling of malaise, particularly during the first months of captivity. Much of the bitterness was directed toward the officers who had, at the direction of the Japanese, reassumed their positions of authority over their particular units.[404] Their separate accommodation, extra food and other privileges did not go unnoticed by the rank and file, including men of the Signal Corps.[405] The atmosphere wasn’t helped by the decision of the Japanese in March to begin paying the officers.

On the other hand, the officers brought some discipline and organization to a difficult situation. By the end of January, “Force C Orders” were being written up regularly, including ration strength returns, appointments and promotions.[406] The men were mustered each morning for roll call and physical training.[407] Scrounging parties were organized and returned with all kinds of supplies and useful materials. The officers also got permission to send out burial parties to look after the remains of fallen Canadian soldiers. Repair crews were marshaled to work on improving the latrines, plumbing and cooking facilities.[408] So all in all, while there was resentment, as one soldier put it, “in retrospect, it kept the morale up a little bit insomuch as the discipline was maintained.”[409]

Gradually the period of shock, of gestation, was drawing to a close and new shoots of vitality began to appear here and there. The instinct for survival asserted itself. Rolly D’Amours, who spoke Chinese, was a language freak and gathered a few cohorts to study Japanese. George Grant and Jack Rose joined him, taking lessons from Rance, the Eurasian interpreter.[410]

In addition to the daily parades and various work parties, the number of other organized activities began to grow. Language classes and other educational offerings were made available.[411] The foraging parties had gradually brought in what was now a fairly large collection of books.

By Feb. 42 two Canadian libraries, one for each unit, were in operation at North Point Camp. At this time each library consisted of about 100 books, practically all fiction, most of the books having been originally the property of the Hong Kong Electric Co. library, although some had found their way into Camp through the efforts of working party personnel. The daily circulation of books in each library at this time was about 100%, with a consequent rapid deterioration in their condition. To offset this, a book press was made in Camp from an old automobile jack and with this and an assortment of borrowed knives, needles, and thread, and with paste made from ground rice, the books were kept in a state of fairly good repair. Moreover, during this time, a book was carefully taken apart to study the art of binding, thus being laid the foundation of a great camp industry which was eventually to become the special book repair section of the library service.[412]

Will Allister was delighted with the availability of books. He saw reading as an antidote to their depression and appointed himself librarian for the Headquarters hut.[413] A number of the Signals, including Jim Mitchell and Blacky Verreault took up his offerings. Blacky wrote in his diary, “I’ve found a way of time killing between meals without constantly thinking about food; it’s to bury myself in reading.”[414]Even though the books were in English, not his first language, he managed to read three in less than a week!

Another diversion was provided by a few Winnipeg Grenadier bandsmen who had managed to save their instruments. Evening concerts were held on Saturdays, with the sounds carrying throughout the camp.[415]

Last evening I was happy for a few hours. I had saved some bread and made myself some toasts on a small fire while the Grenadier Orchestra in the next hut was playing dance music. During these hours I forgot this hell. (Blacky Verreault, February 22, 1942)[416]

Whether it was instructional classes, books or music, anything that took the prisoners’ minds off their situation was welcomed. It wasn’t just the living conditions or their unsavoury diet that made life difficult.

And those Japs you know, they were so cruel. If any Chinese came along the sidewalk and walking on the side the prison was on, the guard standing out in front of the prison camp would start working on them. Throw them up in the air – they’d fall on the cement – things like that. (Bob Acton)[417]

Both Will Allister and Blacky Verreault wrote about atrocities they witnessed against Chinese men, women and children.[418] Similar incidents outside the fence at North Point were recorded by a Winnipeg Grenadier officer, with the simple but telling comment, “don’t know what they’ve done.”[419] In the months and years ahead, the POWs would too often see and experience first hand the cold-hearted actions of their Japanese captors.

Ottawa, January, 1942

On January 26, the Secretary of State for External Affairs received the first communication report from the British Embassy in Chungking, China regarding estimates of casualties. It was sketchy at best and offered a, “Guess, only guess,” that a third of the Canadian force was either killed, wounded or captured during the battle and the rest taken prisoner when the colony surrendered.[420] On February 4, news reports from Ottawa were quoting the estimated casualties and it was being suggested that the government was withholding the numbers until after some upcoming by-elections. These accusations were said to be “absolutely false.”[421] The next day, External Affairs received an unsettling cable from the High Commissioner for Canada in Great Britain:

…quotes a reliable source as reporting bad conditions… at Hong Kong…. Conditions in the military internment camps are also bad and dysentery is reported prevalent.[422]

It noted that steps were being taken to obtain confirmation of the reports and suggested that a request be made to the Japanese to have a representative of the International Red Cross sent to Hong Kong to investigate.

It is further urged that this information should be treated in the strictest confidence and no publicity at all should be given to this report.

On February 9, another cable arrived from the High Commissioner, the contents demonstrating how little was known about the fate of the Canadians, even six weeks after the fall of Hong Kong. Again the suggestion was made that a request be sent to the International Red Cross asking for a Hong Kong visit and for information about Canadian soldiers.

We should welcome detailed statement on each of the following points:

a) Location of prisoners of war and internees;

b) Treatment with special reference to food and medical attention;

c) Lists of names of prisoners of war and internees;

d) Lists of killed or missing.[423]

The message also indicated that the government was prepared to supply a Red Cross ship with food and clothing for prisoners and internees.

The whole issue of food and supplies had now been picked up by the news services,[424]and on February 17, Canadian Press released a story about the reports of atrocities. In the House of Commons, Prime Minister King said the reports should be treated as rumours that would need to be verified. M.P. Tommy Douglas concurred:

…suggested reports of barbarity involving Canadians should be withheld until verified because of the harrowing effect on the minds of soldiers’ relatives.[425]

About a week later, the government received confirmation through a Canadian official in the U.S. who relayed information from a British officer who had escaped from Hong Kong. He reported numerous atrocities including rape and execution of nurses, and deplorable conditions in the prison camps.[426] The government still wanted to keep such reports secret, but it was now clear that more questions were going to be raised in Parliament and, as one official put it, “the cat is out of the bag.”[427]

Defence Minister, Col. J. Ralston now released information about casualties. Based on figures provided by the Japanese through Argentinian intermediaries, Ralston regretfully admitted that 296 Canadian soldiers must be regarded as dead or missing, and 1,689 taken prisoner.[428] Newspapers across the country carried this story and so, for the first time, family members of “C” Force soldiers had some sense of the magnitude of the situation. But it was just general information and there would be a long wait before news about specific individuals would be delivered to the anxious families. In the meantime, comfort had to come from organizations like the Royal Rifles of Canada Prisoners of War Association. Families of R.C.C.S. men at Hong Kong received a letter in late January saying that the Association had been approved by the Adjutant General to keep in touch with next-of-kin of men in the “Ancillary Units.” The letter noted that the Association now had a permanent staff and was raising funds for the purchase of cigarettes, games, magazines and “other comforts” that would be sent to the POWs “when conditions permit.”[429] It’s not hard to imagine how anxious those families would have been, and their worries were undoubtedly heightened by the news reports and editorials published during the next few weeks about deaths of POWs and numerous Japanese atrocities.[430]

General public anger towards the Japanese was increasing as well, particularly in British Columbia. Prime Minister King was very concerned that if there were anti-Japanese riots there would be reprisals against Canadian prisoners in Hong Kong.[431] To reduce tensions and deal with perceived security threats, the government ordered thousands of Japanese Canadians to be moved to camps away from the B.C. coast. While reducing the risk of racially motivated altercations, this action did little to diminish the growing antipathy towards the Japanese. Calls for cooler heads to prevail were heard and read by people across the country. Perhaps the March 18, 1942 editorial in the Vancouver Sun best summed up the prevailing logic:

…because the Japanese have made beasts of themselves, [it] is all the more reason why our treatment of Japanese in Canada should be completely exemplary of the rights and principles expected of a Christian country.[432]

North Point Camp, March, 1942

After three months the dysentery got much worse and beside the huts were little ditches, cement ditches and they were full of blood because the fellows couldn’t get to the toilets. (Ray Squires)[433]

Poor diet, unhealthy sanitation and living conditions, and the ever present swarms of flies made the camp a cauldron for disease. More and more men were suffering from severe diarrhea and dysentery. The hut set aside as a hospital was overwhelmed. The stench was overpowering, but friends of the ill did what they could, emptying buckets, cleaning bodies, changing bed clothes.[434] Many men were left to suffer in their sleeping huts, relying on the assistance of their comrades for frequent trips to the latrine and the inevitable clean-ups.[435] Blacky Verreault’s diary mentions his “terrible di arrhea” in March, and he lamented, “A sick person he re is of no interest to anyone but those who benefit of his food ration.”[436]

Ray Squires described lying on a stretcher all night outside the hospital ward waiting for a space. He eventually was brought in to use one of the “toilet holes” and the medical officer gave him some magnesium sulphate to treat his dysentery.[437] His diary entry on March 18 mentioned he had a mild case of beri beri, which he said was becoming more frequent, noting that Lee Speller’s legs were also badly swollen.[438] He later remarked that they all had septic throats and some were developing trench mouth.[439] Wes White, Tony Grimston, Ted Kurluk and John Little were all in hospital with dysentery that spring. Johnny Douglas celebrated his twentieth birthday on May 22 with a bout of tonsillitis. By then, White was noted in the North Point Hospital records as having “chronic dysentery” and Little’s case was so bad he had to be transferred to Bowen Road Hospital.[440] He never recovered and died there on June 5, 1942.[441] Blacky Verreault recorded the event in his diary:

Poor Johnny! He had told me of his plans. He lived on the Pacific Coast and was gonna buy himself a fishing boat and practice this trade but destiny willed it otherwise. Another family in tears! Poor rascal to die like this after all his heroic deeds in battle![442]

The day after his death, Signalman John Samuel Little was buried in Grave Area No. One outside Bowen Road Hospital.[443] He was twenty years old.

Not surprisingly given their diet and various illnesses, weight loss among the POWs became common throughout the camp. By mid- April, Walt Jenkins had lost 45 pounds,[444]and Blacky Verreault’s weight had dropped from 184 to about 150 by his twenty-first birthday on April 14.[445] On May 26 he wrote about the toll being taken on their bodies and spirit:

Do you remember my fellow linemen, Walt, Ted and Ray? Poor Ted as I mentioned yesterday, has dysentery. Walt is as thin as a skeleton and his pale eyes are circled black; he thinks too much the poor man. As for Ray, nothing: war and captivity have dulled him into a point of indifference.[446]

Ray Squires’ perceived “indifference” was certainly not reflected in his diary entries during the spring of 1942. He wrote regularly about details of their food rations, the health of the men, and occasional notes about other goings-on in the camp. His observations about cigarettes reflected the importance of “smokes” in their lives as POWs:

Cigarettes are the medium of exchange, main brands are Golden Dragon and United (Chinese) worth 9 cents pkge of 10 in peace time….

About 40% of internees will trade a slice of bread or a ration of rice for a cig. The craving for smokes is intense. Half the cigarettes smoked are shared individually by a least 4 men, in spite of the regulation put up by M.O. [Medical Officer] barring same due to spread of dysentery.

I never thought I would see Cdn. Soldiers bumming and scrambling for butts from Jap guards but such is the case. (March 6) [447]

I went out on a truck to help load wood yesterday, the Jap guard gave me 2 cigarettes, 1 I traded for bread, the other I will trade for a slice tomorrow. Can you imagine men (they come and ask or coax) trading bread here where men are always hungry, for a smoke. (March 29)[448]

For some of the men, tobacco addiction provided a type of diversion from their bleak situation as they searched, traded, or otherwise found ways to procure cigarettes. Like the recipe hunters, they had a focus to keep their minds occupied and to pass the time.

By February there was also a growing list of organized activities available. More educational classes were offered, including: maths, radio, languages (including Japanese), shorthand, bookkeeping, sketching, public speaking, civics, electrical theory, first aid, telegraphy, insurance, and poetry writing.[449] George Grant and Jack Rose (who had been good with languages in high school) signed up for Japanese lessons and became quite fluent.[450]Book-binding classes were held and many of the men made their own little books. Les Canivet, a member of the Ordnance Corps, produced a Hong Kong memento book in which he had most of the Brigade Headquarters men, including the Signals, record their names and addresses.[451] In his own camp-produced notebook, Don Penny recorded notes on batteries and electrical current, tables of weights and measures, and, in marked contrast to the other technical content, a series of poems and song lyrics.[452]

Will Allister was a trained artist and in addition to doing some of his own work, he started a weekly art class, “pencil and paper all that were required.”[453] A major handicraft exhibition was held towards the end of May and given the conditions of the camp, the array of items on display was quite remarkable. A Grenadier officer wrote:

Some of the carvings and woodwork are really wonderful: rings made of silver coins, gloves, socks, mitts knitted on needles made of wood, drawings, etchings, and carvings, inlaid cigarette cases, boxes, canes and dozens of things.[454]

Allister contributed a number of sketches for the show.[455]

One of the main diversions was music. By May the Saturday concerts with the Grenadiers band were a regular occurrence and additional entertainment offerings were happening on other nights throughout the camp. Padre Laite took in one of the performances.

I attended a concert at Brigade hut last night and greatly enjoyed it. The fellows entered into the spirit of the hour and gave themselves to it with great zest.[456]

A choir was organized, primarily to sing at the weekly church services. Another musical highlight prompted Blacky Verreault to write in his diary.

There’s a piano in the camp and last evening we received permission to transport it to our hut and for three hours, we forgot our misery. It reminded me of the wet canteen back at camp in Canada. There’s an accomplished pianist and a remarkable baritone in the Grenadiers and they joined their talent in entertaining us.[457]

Once the weather began to improve in the spring, a large open area of the camp which was used for parades became the venue for various sporting activities. A softball league was formed and volleyball, soccer and horseshoe pitching were also available for those well enough to participate. Softball was the most popular, with enthusiastic crowds watching the games, particularly the league finals between the Royal Rifles and Grenadiers teams. This was in spite of the lack of equipment. Initially, they only had one softball, “it being re-sewn every evening after being played with all day.”[458] But even with the various activities and entertainments, for some, the main antidote to their depressing situation was thoughts of home.

I can honestly say that the main thing I live for is to be back with my wife, that thought makes this life tolerable, and gives me an optimistic viewpoint so sorely needed here.(Ray Squires)[459]

For a few of the men in the Signal Corps, March 23, 1942 was of some significance, even if it was just related to their personal Record of Service, rather than marking any actual change in their lives. That day, the “Force C Orders, North Point Internment Camp” contained the following “Appointments and Promotions:”[460]

K34027 Cpl. Penny, D.A. RCCS is promoted to the rank of Acting Sergeant with pay vice K35468 Sgt. Sharp, C.J., killed in action, effective 21 December, 1941.

K34757 L/Cpl. White, W.J. to L/Sgt. effective 16 November, 1941

D116314 Sgmn. Verreault, J.O.G. to L/Cpl. effective 16 November, 1941

P7541 L/Sgt. Routledge, R.J. to full Sgt. effective 16 November, 1941

K35468 L/Sgt. Sharp, C.J. to full Sgt. effective 16 November, 1941

K11054 L/Cpl. Keyworth to Acting Corporal, effective 21 December, 1941

K36009 Sgmn. Kurluk, T. to L/Cpl. effective 16 November, 1941

K83926 Sgmn. Speller, L.C. to L/Cpl. effective 16 November, 1941

In spite of the dispassionate process of military record keeping, it’s hard not to reflect on the official promotion of Charlie Sharp to full Sergeant more than three months after his death by shellfire in that house on the hill at Wan Chai Gap. How might his fellow Signals, now prisoners of war, have reacted to the posting of that order? Perhaps, as Gerry Gerrard put it, commenting on how little discussion the men had about what happened during the days of battle, “I guess we had more important things on our minds at the time.”[461] Blacky Verreault didn’t even mention his promotion in his diary until more than two months later, and even then it was an afterthought:

I forgot to mention that I was promoted for having done a good job in keeping our lines of communication open during the fighting. But I might lose that stripe for being somewhat impudent with one of our brave officers.[462]

Surviving the conditions at North Point Camp during the spring of 1942 took all the energy, will power, skills, and sometimes ingenuity of the POWs living there. Blacky Verreault’s personality, which he acknowledged could tend towards the abrasive, led him to take a unique approach to his bunking arrangement in the Brigade Headquarters hut.

As I like my solitude, I hung my hammock two feet from the roof and climbed to it on a home made ladder. It’s like a private dwelling. It requires some physical effort to get there but it’s well worth it. Nobody bothers me there. I made a shelf for my soap and toothbrush and a line to dry my wash (three feet of barbed wire stretched between two beams)… but I call it home.[463]

Away from the bed bug infestations and close human contact, it was his personal isolation chamber. It also led to some dramatic entrances, when he “swung down by a rope like Tarzan,” Will Allister wrote.

At one point Jenkins had run afoul of a guard for breaking a rule. The guard bellowed at him, firing questions he couldn’t understand. It looked like a beating coming up. Jenkins was backed down the centre aisle of our hut at bayonet point, trying vainly to explain. Blacky, watching from his roost, came swinging down on his rope like a dark thunderclap bursting from the heavens.[464]

The startled guard turned and left, leaving a group of no doubt relieved, but also chuckling Signals.

In those early months of captivity, the Japanese guards were apparently rather careless in their duties.[465] A high wire fence guarded the perimeter of the camp, and for a time the prisoners were ordered to stay at least ten feet from the wire. When extra strands were added and electrified on April 16,[466]security became a bit tighter. But the latest measure was not without its unintended consequences, as recorded by Ray Squires:

The electric fence around our prison got its first victim today, the guards Doberman Pincher [sic] dog, he just brushed against one wire.[467]

In late April and early May the Japanese laid out and constructed two large latrine huts which “appeared to be a standard pattern in the Japanese Army.”[468] The design was basically a concrete trough emptying into a pit outside the building. There were wooden seats with partitions built above the troughs. Ray Squires recorded:

They built a toilet for us, it has taken 58 Chinese 8 days, the bldg. is 14 x 30 with no plumbing.[469]

It might have been a bit primitive, but at least it was better than hanging on a wire fence over the seawall. About the same time, there was another sanitary improvement – a distribution of soap. But one small bar had to be divided and shared by twelve men![470] Shortly after, each man was issued a toothbrush, a small portion of tooth powder and a small towel and facecloth.[471]

More security wire and new latrines weren’t the only camp developments the Japanese initiated at North Point around that time. Forms were given to each man to fill out, stating his name, date of birth, rank, date and place of capture, and any “special talent” he might possess.[472] Another administrative order came down asking the chaplains to gather detailed information about men who had been killed. Captain Deloughery was assigned to compile the report on Brigade Headquarters casualties.[473]

On May 23, Capt. Billings and some of the other officers left camp with a Japanese military official, “for an outing and conference.”[474] That afternoon, all the prisoners were ordered out on parade and addressed by Col. Tokanaga, the Japanese Commandant. He insisted that everyone sign an agreement:

I hereby swear that I shall not make any attempt to escape whilst I am a prisoner of the Imperial Japanese Army. Dated this __ day of __ 17thyear of Showa.

The Commander-In-Chief

Hong Kong Prisoners of War Camp

Hong Kong

Signed _____________ [475]

There was much protest from some of the officers that this was illegal under international law, but ultimately they recommended that their men sign, though under protest. One Canadian refused and was taken away by the Japanese guards.[476] He, along with some others from Sham Shui Po Camp were escorted to a nearby prison,

…put in a very small cell where they were forced to kneel all the time, no sanitary conveniences of any kind, given a little rice everyday and beaten at least once a day; eventually they signed too.[477]

Gradually, persistently, the Japanese were making it clear through speeches and their actions that the Canadians would be prisoners for an indefinite period, and that they should just accept that this was the way things were going to be. Each man was assigned a POW number which was to be sewn onto the right side of his shirt.[478] They had to memorize it and learn to say it in Japanese; if you didn’t, “violent blows to the face or stomach administered by the guards would help you remember.”[479]

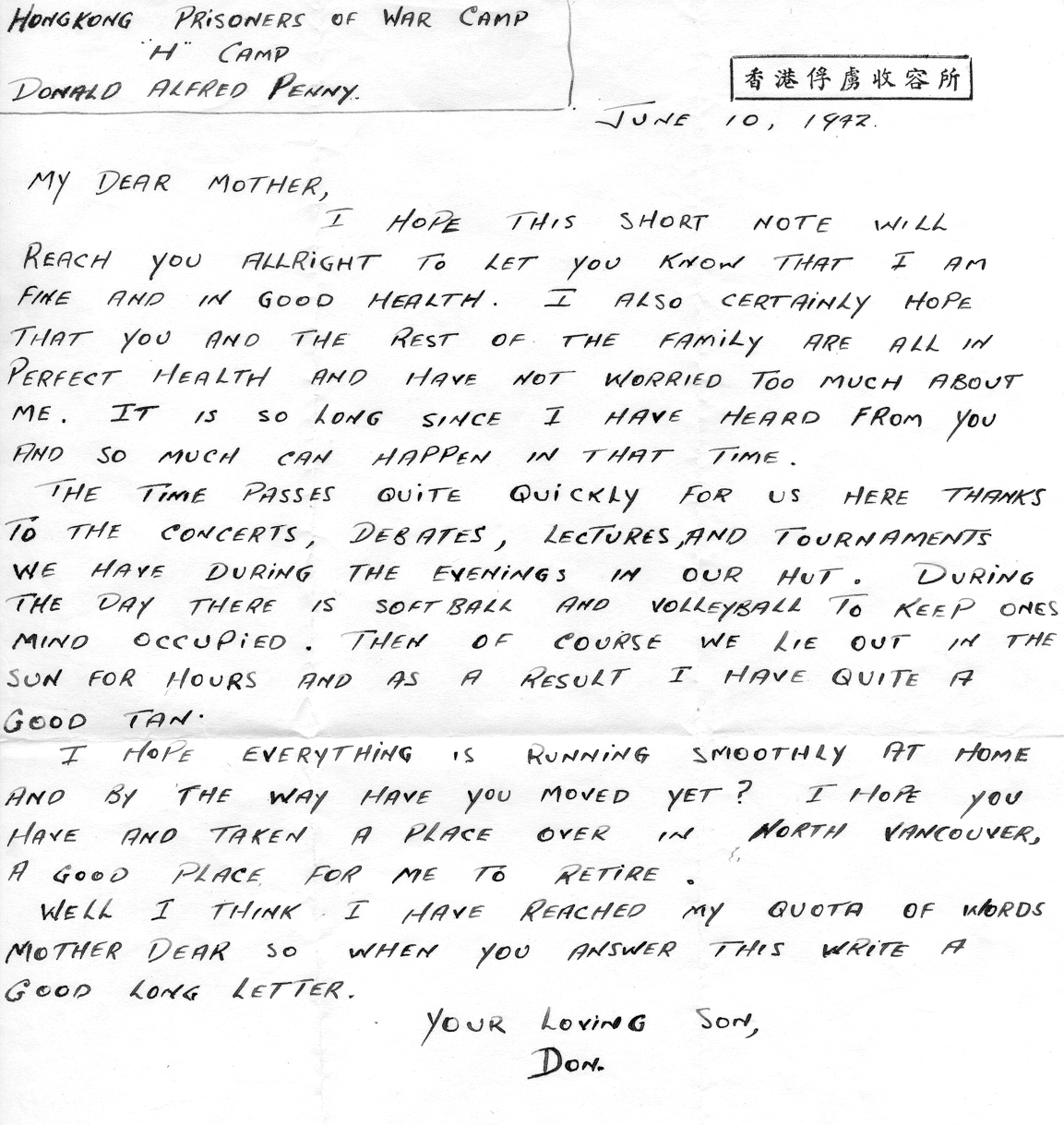

But then, in the midst of all the sickness, deplorable living conditions, and constant repression, the Japanese confirmed rumours that had been swirling around the camp that a few prisoners would be chosen to broadcast radio messages, and, even better, each man would be allowed to write a letter home.

Hong Kong Prisoners of War Camp

“H” Camp

Donald Alfred Penny

June 10, 1942

My Dear Mother,

I hope this short note will reach you allright to let you know that I am fine and in good health. I also certainly hope that you and the rest of the family are all in perfect health and have not worried too much about me. It is so long since I have heard from you and so much can happen in that time.

The time passes quite quickly for us here thanks to the concerts, debates, lectures, and tournaments we have during the evenings in our hut. During the day there is softball and volleyball to keep ones mind occupied. Then of course we lie out in the sun for hours and as a result I have quite a good tan.

I hope everything is running smoothly at home and by the way have you moved yet? I hope you have and taken a place over in North Vancouver, a good place for me to retire.

Well I think I have reached my quota of words Mother Dear so when you answer this write a good long letter.

Your loving son,

Don.[480]

Hong Kong Prisoners of War Camp

H. Camp

J.D. Beaton.

Dear Mother and Dad

This is once I can truthfully state that letter writing is a pleasure and from now on it will be a monthly one as we are allowed a two hundred word letter per month.

How is everything going with you all? Fine and dandy I hope. As for me – I’m in excellent health and being treated well. I really miss everyone very much but some day we will get together and all I can say for that is happy day.

Speaking of happiness – congratulations on your wedding anniversary and best wishes for all the birthdays I am missing.

Would you give my regards to the Cowley family and Mrs. Laidlaw? And to anyone else I know? I imagine there are quite a few changes in the last six months around the neighborhood. How about all the choice gossip and scandal when you write?

This finishes my allotted number of words so I’m afraid I’ll have to call it quits. For this month. So God bless and keep you all.

Love to all

Don[481]

It is difficult to reconcile the upbeat tone and positive impressions given by these letters with the realities of life at North Point, and the condition of the men, particularly Don Beaton, whose health had been of great concern to some of his fellow Signals. Even the whole process of producing the letters was a trial. First, a long list of restrictions was provided. Then, after most of the men had written their letters, they were told they would have to do them over again, “shorten to 200 words and not ask for a single thing.”[482] And then, of course, they were censored; any perceived deviation from the restrictions meant a rewrite. The letters were hand printed all in capital letters on sheets of paper provided by the Japanese. In the upper right corner was a chop (Japanese stamp) which translated: “Hong Kong Prisoner of War Internment Camp.” The letters were placed in special envelopes which were marked with a chop signifying “Prisoner of War Mail,” and another consisting of the Japanese censor’s personal symbol and characters indicating that the censorship was complete.

Without the imposed regulations and censorship, it’s hard to say what the men would have written. Although they may have wanted to describe the horrible conditions, the thought of their loved ones knowing how bad things were and the worry it would have caused may have been reason enough to omit the grim realities. At the same time, it seemed that some of the men tried to give subtle indications in their letters that things weren’t as rosy as they were describing. The sarcasm in Don Penny’s comment about lying in the sun for hours would have been picked up (he wasn’t fond of the heat), and his reference to moving to North Vancouver would have been puzzling for his family, thus suggesting they should be taking the contents of his letter with a large grain of salt.

As they were approved, the letters were batched up and eventually sent out from the camp. On June 11, Blacky Verreault wrote:

My letter is all written and in the hands of the authorities for sending. It’ll probably arrive home in a month.[483]

Whether others shared his optimism is not known, but not surprisingly, the reality was much different. Although one batch of mail made it to Canada in late August, others took considerably longer. Don Penny’s letter arrived in Ottawa more than a year later, and after being examined by government officials, was posted to Vancouver on September 10, 1943.[484]

In the midst of all the letter preparations, another communications event was taking place. In early May, word was received in camp that ten Canadians were to be selected to record messages that would then be broadcast by radio to Canada.[485]

My friend Allister is shaking with excitement. He has been chosen to broadcast a message in English, of one minute duration. This will be heaven sent for his mother who is very sick and worried to death undoubtedly. I truly hope it happens. He was kind enough to include my name in his message. (Blacky Verreault)[486]

On June 3, the selected messengers were taken from camp across the bay to Japanese headquarters in Kowloon. There they recorded their carefully scripted and censored messages.[487] Although indications were given that the broadcasts would be done soon, as was the case with the letters, it would be a long time before messages from Hong Kong would be received in Canada. Grenadier Tom Forsyth added a footnote to his diary entry regarding the broadcasts, stating his message wasn’t heard in Canada until October, 1944![488]

Canada, April, 1942

Efforts by officials from External Affairs in Ottawa to obtain information about Canadians in Hong Kong continued, but with little success.[489] However, in a letter to next-of-kin of “C” Force soldiers, the Department of National Defence raised the possibility of mail communication with the men who were now prisoners of war.

April 15, 1942

We are now informed through the International Red Cross of the possibility that mail addressed to prisoners of war at HongKong[sic]may be forwarded within the next thirty days. It is possible that one next-of-kin parcel may also be permitted. Letters and parcels should be addressed as follows:

(Write name of soldier here.)

(Write name of regiment here.)

(Write soldier’s number here.)

Taken Prisoner of War at HongKong,

Care Force “C”,

General Post Office,

Ottawa, Ontario

The above method of addressing must be carefully followed, and the letter can be mailed at your Post Office in the regular way.

All letters will be censored in Ottawa, so please refrain from writing any information useful to the enemy.

As letters on arrival in Japan will also be censored by the Japanese, it is suggested that no recriminations against the enemy be introduced, as it may result in the letters failing to reach those to whom they are addressed.

We would also point out that we have not as yet received a list of the dead and missing in the force at HongKong, with the exception of the nine names published in the newspapers some time ago.

We realize your great anxiety to communicate with your son and to have word from him, and every effort is being made to arrange for a return mail from the prisoners of war at HongKong. You will be immediately advised if such an arrangement is completed.

We are also hoping to arrange for the dispatch of food parcels through the Canadian Red Cross, as well as a full supply of medicine, clothing, cigarettes and tobacco, books, magazines, and educational reading matter, games and other comforts. The only limit to the quantity of these items forwarded will be the space available in the ship.

While we believe there is now reason to expect mail and parcels to go forward we are compelled to point out that the present negotiations may fail to materialize.

As the officer specially charged in the Department of National Defence with the welfare and care of prisoners of war, I will be pleased at any time to answer any further inquiries you care to address to me care of this Department at Ottawa.

Yours truly,

(F.W. Clarke) Lt.-Col.[490]

Press reports continued to paint a bleak picture of the situation in Hong Kong, although expressions of outrage that followed earlier reports of atrocities were not in evidence. Unofficial reports from the Far East received by the government were digested, and then carefully worded statements were made public, often through the House of Commons.[491]The war in the Pacific was still very much in the news, and Ottawa was under pressure to provide stronger defence measures for the coast of British Columbia, home to many of the Signals’ families. Polling by the Canadian Institute of Public Opinion during the spring of 1942 showed that 56% of respondents thought it was “likely” that Japan would attack the west coast within the year.[492]

In early May, the first list of prisoners, all officers, was made public.[493] Provided by British officials in China, it referred to thirty-five named officers and about 640 other ranks (unnamed) at North Point Camp. That number of POWs and the fact that Capt. Billings was not on the list suggests that the information was obtained prior to the transfer of other Canadian POWs from Sham Shui Po on January 23, 1942. But there were finally some encouraging words coming out of London, with reports in the press that although the Japanese were still being uncooperative regarding prisoner information, the food situation in the camps was said to have improved.[494]

In Ottawa on June 5, 1942 (the same day John Little died in Hong Kong), the report of a Royal Commission on the Hong Kong operation was tabled in the House of Commons. An editorial in the Toronto Daily Star the next day began:

It will be a source of satisfaction to those whose loved ones were lost or taken prisoner at Hong Kong to know that they were not the victims of bungling or incompetence.[495]

Opposing views from politicians and other critics were given ample space in newspapers across the country during the weeks that followed. One Conservative went so far as to assert that, “the actual facts brought out in evidence were blood-curdling,” and, “inexcusable blundering, confusion and incompetence marked every stage of the proceedings.”[496]

Families of Hong Kong soldiers had been told about a possible shipment of food and other supplies back in April. Finally, on June 17, Canadian Press was reporting that relief supplies had left from New York that day. The diplomatic ship Gripsholm was carrying 23,824 food parcels plus drugs, medical equipment, cigarettes and other items.[497] Unfortunately for the POWs in Hong Kong, it would be months before they would see any of these badly needed supplies, and as it turned out, much of the shipment would never make it into their hands.

North Point Camp, June, 1942

The Japs are putting us to work now. About one hundred men left the camp yesterday. When they returned they were queried by us as to the nature of the work. For fifteen cents a day, they had become pic[sic]and shovel engineers. (Blacky Verreault)[498]

Since the early days at North Point, work parties outside the camp and fatigue duties inside the fence had been part of the regular routines organized by the officers. Many men preferred the outside work parties because they were able to get away from the camp, collecting food rations and other supplies, and gathering wood for the cooking fires. Both Blacky Verreault a enjoyable part of my life. 250 soldiers a day go out to work on the airport. I have not volunteered.[504]

With the work on Kai Tak now a major occupation for the POWs, the daily routine changed, at least for those who were on the work party. They were up about 5 a.m., and by 6 would be off to work, returning around 7 p.m.[505]

Bob Acton recalled:

When we used to march down from North Point, we had a couple of blocks to go and get on a barge with a tug and take us to the airport across the water. All these Hong Kong Volunteers, their children and wives would come down and be standing on each side becaus5 at that time the Hong Kong volunteers had been taken prisoner too.[506]

Will Allister later wrote about his Kai Tak experience.

Work parties lined up before dawn to be counted and recounted for hours before being ferried over to Kai Tak. It was dull, grueling labour in the murderously hot sun, draining what little substance we had left.

With pick and shovel, we slowly pulled down two sacred Chinese hills, some used as burial grounds, with thousands of ancestral ghosts screaming around us as we sweated away. The dislodged earth was shoveled into baskets attached to bamboo poles which rested on the bony shoulders of two prisoners who carried it away. Wally Normand and I were a team of carriers. I needed him. Humour was in short supply here. One had to work at it. To attack the fatigue and monotony of the long hungry hours, we turned our job into a rhythmic Conga walk-dance, singing: “Coolie, coolie Conga! Coolie, coolie Conga!” The Ritz brothers in Kai Tak.…[507]

From Blacky Verreault’s diary, June 21, 1942:

I got up this morning stiff as a board. I spent all day at the airport yesterday with a pic [sic] and shovel. There were two hundred of us working under this torrid sun and many fainted from the exertion and heat. The day’s work took a lot out of me and I’ll probably be stiff for some time. For the first time since my imprisonment, I didn’t attend mass this morning.

I usually wake up early and on my own but this morning, it took the voice of the staff sergeant to take me from my deep sleep. I worked all day in the sun without my shirt and to get me darker, you’d have to roast me.[508]

Working at Kai Tak did have some benefits beyond a change in surroundings and a tanned body. The men were paid for the work, although it was a pittance – fifteen sen per day, or enough to buy ten cigarettes.[509] It also put the prisoners in close contact with many Chinese labourers, some of whom were part of the Chinese guerilla movement. This allowed the passing of information back and forth and provided a source of much needed medications – something not provided by the Japanese for the growing number of men at North Point who were ill.[510] One of the jobs at Kai Tak provided the opportunity for the men to engage in some sabotage. Don Beaton recalled:

We worked on the mixing concrete for it. So we didn’t pay attention to what the Japanese were telling us. We just mixed it the way we felt like it. So it looked pretty good when it was finished.[511]

Bob Acton:

When we were doing the airport at Kai Tak – I think there was about eight men on a square maybe as big as that room [3 m. x 3 m.]– and each group would use a different formula. The Japs would tell us to mix so much cement with so much water with so much sand. So each group said, well I’ll put a lot of sand, and another would say, I’ll put a lot of water, and, I’ll do too much cement, or not enough….[512]

Whether or not the later stories were true of Japanese planes crashing the first time they tried to land, just the thought of fouling things up for their captors was enough for the men to risk the beating that would certainly come if they were caught. They all had seen the brutality of their Japanese guards.

Beatings were commonplace – at one point he had his teeth kicked in – and Japanese was taught by word association. “A guard would say the word for ‘shovel,’ slam us across the shoulders with one, and get us to repeat the word. If we got it wrong the session was repeated.”[513]

As the summer wore on the work continued, but the deteriorating health of the prisoners due to malnutrition and disease began to affect the work parties. Still, the Japanese were determined to have their quota of men at the airport each day. Lee Speller recalled,

As you know, we were taken over every day on a barge to work at enlarging the Kai Tak Airport. They pretty well forced you over there whether you were sick or not. You had to be actually dead on your feet before you could get out of the work parties.[514]

A report filed after the war regarding Canadian prisoners at Hong Kong summarized the situation:

Many men just out of hospital, or suffering from diarrhea, were compelled to go on these working parties to make up the numbers, working parties of as high as 400 Canadians some times being ordered by the Japanese. Although strenuous efforts were always made by the Canadian administration to reduce the numbers going out, these met with very little success, the usual excuse given by the Japanese for refusal being that the size of the working parties was set by the Governor’s Office.[515]

Through the summer of 1942 the number of POWs afflicted by various illnesses and medical conditions continued to grow. Ray Squires’ diary entries between early June and early September chronicle the worsening health of the men around him:

Ted Kerluk [sic]has gone to Bowen Rd. [Hospital]. Many are losing weight.… (June 6)

We had another dysentery death, an elderly Grenadier. (June 23)

Of the sixty men in our hut 12 have large body sores which don’t want to heal. Ted K. has pleurisy with dysentery. Under present food and medical conditions I doubt if 15 of them would last another four months. (July 16)

The diet (no meat, fresh vege, fruit, butter or milk products) is beginning to tell. About 8% of the boys can no longer walk around, they have severe continuous pains in the feet, which may be temporarily relieved by bathing in cold water. Three weeks ago I got a blister on my foot from my wooden sandal. It has developed into mild blood poisoning. (August 9)

We now have 297 cases confined, most of them can’t walk or sleep because of pains in the feet. The only relief is cold water. All huts are under quarantine with [no]softball and mass parades etc stopped due to 4 cases of diphtheria. About 30 percent of the boys have sore throats and colds anyway. Everybody sleeps outside when possible to get away from the bedbugs. (August 16)

3 men, 2 Grenadiers, 1 Rifles died last week, 1 from sore throat, 2 dysentery and malaria. (August 20)

3 men, 2 of the Rifles, 1 Grenadier, died last week. 2 more, 1 Rifle & 1 Gren. This week. Last week 70 per [cent]of B.H.Q. [Brigade Headquarters]had sickness of some kind and were taking treatment. (September 10) [516]

Blacky Verreault described his own ailments:

We face the strangest diseases. Personally, I’ve had dysentery twice, an inflamed and swelled throat for two weeks, the delights of a scabby mouth, and for eight days I squirmed from an itchy rectum, followed by two weeks of itchiness of the scrotum. Quite embarrassing![517]

The hospital hut at North Point, dubbed by some, the “Agony Ward,” was overwhelmed, and the preponderance of dysentery cases made it a particularly unpleasant place. Will Allister wrote:

The stench was ferocious and made visiting a friend an ordeal. Men emptied their bowels where they lay, too weak to rise, awaiting their turn to die.

Ted Kurluk had a bad case. He grew weaker and weaker. He was a gentle soft spoken soul. There was a dog-like innocence about his large brown eyes that gazed out of their deep shadowed sockets with an air of uncomplaining hurt. He wanted no part of the hospital. Blacky and Jenkins, fellow linesmen, took turns carrying him to the latrine through cold, rain or heat, waiting patiently, wiping him, cleaning him up. Sometimes they carried him on their backs.[518]

The dysentery that took the life of Signalman John Little did its best that summer to claim others in his unit. Ted Kurluk, Wes White, Jack Rose, Tony Grimston and Ron Routledge were all treated at the North Point hospital during that time.[519]

Vitamin deficiency caused other ailments which added to the discomfort of the men. Pellagra produced open sores in the mouth and on other parts of the body. Failing eyesight was common. Lee Speller later recalled,

At that particular time it was my eyesight that was going. Oh, there was three weeks there where all I could tell was the difference between daylight and darkness….

And oh no, Squires fed me for a time there – a couple of weeks because I couldn’t see to eat.[520]

“Strawberry balls” was another common condition that described the presence of red, swollen testicles. But perhaps the most painful and debilitating affliction was what they called “electric feet.” Will Allister, Don Beaton, Johnny Douglas, Jim Mitchell, Blacky Verreault and Walt Jenkins all wrote or told about having this condition. Walt Jenkins said,

I couldn’t think of any worse torture to put on anybody than to have that electric feet, you know. Like I say, I can tell you about it but the only way you come close to it is if you had your ears frozen or something when you were a kid and they started to thaw out. That’s very similar to it. But it’s day and night.[521]

For weeks, Blacky Verreault recorded diary entries about electric feet:

For five days now, I’ve had these shooting pains in my feet. It’s the same pain as when your feet thaw out in the winter. I find it difficult and painful to walk and it’s continuous. Night and day; I barely sleep three hours a night when I finally fall asleep. (July 22)

My sore feet are getting worse. I spend sleepless nights in pain. They give me shots but to no avail. One of my friends has the same sickness and will be taken to hospital soon. (July 23)

My sore feet make me walk like a very old man. The doctor injects me with a marvelous serum lately that has absolutely no effect. (July 26)

Hell! I can no longer walk. Each step is untold pain. There are many such cases in camp and the M.D. says it’s caused by our slow starvation. Bones get soft. It started with the toes, then the foot. Slowly it creeps up the legs and from the knees down, my legs are covered with painful sores which will drive me crazy if nothing is done. (August 8)

I’ve neglected my diary in the last few days due to the excruciating pain caused by my feet and legs. It’s really affecting a lot of guys. Two of them are now blind. The doctor can’t do anything about it, he has no medication and the hospital is full. (August 19)

A sergeant with the same foot ailment as mine went mad today. Poor devil. May God protect me from the same end. (August 28)[522]

Blacky would persevere through months of this affliction and although he suffered greatly his spirit remained strong.

During the summer of 1942 some of the seriously ill POWs at North Point were sent to Bowen Road Hospital, located in the Peak area outside the city of Victoria. Tony Grimston (August 29) and Ron Routledge (September 9) were among those taken across the Island to this facility.[523] While the reason for their transfer was nothing to celebrate, once there, the conditions in the hospital offered a substantial improvement in their lives. Rifleman Ken Cambon, who became an orderly at the hospital, later wrote about Bowen Road:

The change from North Point was like going into another world. We slept in beds, even had sheets and mosquito nets. Clean clothes and washing facilities were available.[524]

Ron Routledge, in a post-war interview, also commented on the excellent treatment he received at the Hospital.[525]

For the men at North Point, the poor conditions and pervasive illness must have been almost too much to bear. But in spite of their situation that summer, the POWs continued to do what they could to keep their spirits up. A second handicraft exhibition was held on July 1, again with a wide variety of items demonstrating the skills and ingenuity of the men who created them.[526] The same day, a minstrel show was performed for the camp.[527] Shortly before his electric feet symptoms began, Blacky Verreault formed a choir with fifteen men. Practices were held every day in preparation for the mass to be held on August 15.[528] The Grenadiers band continued to perform regularly and various theatrical presentations became part of the concert offerings. Will Allister was a prominent figure at these events, referred to as “an accomplished mimic, really a scream in the Fred Allen Radio Broadcast.”[529] Blacky Verreault noted, “When he appears on stage, concert nights, he is cheered like a star. What a man!”[530]

One of the most significant events of the summer was the escape attempt by four Winnipeg Grenadiers on the night of August 20. Ultimately, they were captured and brutally executed, but the ramifications of the attempt were felt by the entire camp. Almost immediately, the Japanese ordered that anyone attempting to escape would be risking death.[531] The camp was organized into groups of five, with each member held responsible if any of the others tried to escape.[532] On the 29th the Japanese were convinced another escape attempt had been made. Shortly after getting to sleep, the men were roused by their officers and the roll was called. Then after being sent back to bed, the lights went on again and the Japanese officers did a bed check, then finally ordered everyone out to the parade square for an alphabetical muster.[533] Ray Squires wrote in his diary,

Had a wild night last night, called out of bed at 1:15 a.m., stood on parade ground in rain till 5:30. got very cold and wet. Escape scare proved false. 13 men collapsed on our parade ground and were carried of[f].[534]

Whether it was the fear of more escapes or other considerations, the Japanese decided to close North Point Camp, and on September 26, 58 Canadian officers and 1373 O.R.s were transferred back to Sham Shui Po.[535]

In September we welcomed the move to Sham Shui Po, our first home, once a proud symbol of power and glory, now a sorry decrepit looking boneyard with doors, windows, even window frames stripped away and replaced by patched boards and packing. Still it was spacious, with its broad avenues and white cement huts.[536]

Only Captain Billings and twenty-one men of the R.C.C.S. made that trip to their new camp, eleven months after their departure from Canada. Of the original thirty-three, four had been killed in action (Bob Damant, Hank Greenberg, Charlie Sharp and Ernie Thomas), two had died of wounds received in battle (Bud Fairley and James Horvath), one had died of sickness at North Point (John Little) and three others (Tom Redhead, Ron Routledge and Wes White) were in Bowen Road Hospital at the time.[537] Within days of their arrival at Sham Shui Po, the Signals learned that two of the three in hospital would not be coming back to join them. Wes White had died on September 25, three years and a few days after joining the 10thFortress Signals in Vancouver. He was twenty-two years old. Five days later, Tom Redhead, 26, had also succumbed to his illness. Both were buried in the cemetery at Bowen Road Hospital.[538] Although their deaths were not mentioned in the Verreault or Squires diaries, Don Penny’s notebook pages of “Casualties Brigade Headquarters” recorded their names under the heading, “Died Bowen Road Hospital (Hong Kong).”[539]

As Will Allister noted, Sham Shui Po was much more spacious than North Point with over fifty huts, plus separate buildings for hospitals, cookhouses, offices, and officers’ accommodation.[540] Capt. Billings was assigned a room with Staff Officer Capt. Bush; Lee Speller was appointed his batman.[541] Each of the 120-foot long accommodation huts for the men had a fireplace in the centre of the concrete floor and two small cubicles partitioned off at one end. Tall windows were located along the walls, but all the glass had been broken or looted. Ceilings had been torn down and plaster board used to fill the openings. Although the buildings were wired for electric light, few bulbs were ever provided. Some beds were available when the Canadians arrived, but most of the sixty-five men assigned to each hut slept on a raised wooden platform along one wall.[542] However, the bed bugs were so bad, Ray Squires noted that many of the men slept outside on the ground.[543] Sanitary facilities were even more crude than at North Point. The lack of plumbing fixtures reduced the availability of showers and consequently, keeping clean was always difficult.[544]

Camp life at Sham Shui Po was similar to what the men had previously experienced. Sentries patrolled day and night and everyone was required to attend two daily parades, even the sick, who had to be carried on stretchers or on the backs of others in order to be present.[545] Although the specific times changed occasionally, the daily routine was generally as follows:

0630 Reveille

0715 Breakfast

0800 Muster Parade

0805-0825 P. T.

0900 Sick Parade and injections

1200 Dinner

1700 Supper

1800 Muster Parade

2100 Lights out warning bugle

2130 Lights out[546]

Ray Squires wrote that at least initially, the food was somewhat better than at North Point: “Breakfast today, Rice sweetened. Lunch Bread 10 oz., Vege soup. Supper, Soup rice.”[547]