Ernie's Story

"Hold Fast for King and Country"

-- an excerpt from the 1941 Christmas Day speechgiven by Hong Kong Governor S. Mark Young

Hong Kong 1941 Nov 20 A.M.11:56

Mrs, E. Hodkinson 759 Spruce St. Winnipeg

"All Well and Safe Writing All My Love-- Hodkinson"

When Irene received this cheerful telegram announcing Ernie's safe arrival in Hong Kong, she had no idea that nearly four years of anxiety and horror would go by before they would see each other again.

Canada declared war on Germany, Sept 4, 1939 and almost immediately new recruits began pouring into Winnipeg to sign up with the Winnipeg Grenadiers. Young Canadian men in 1939 were loyal to Canada, their English King, and to the British Empire. For most of the new recruits, it was both a feeling of patriotism and a sense of adventure that motivated them to volunteer for active duty. Canada was still in an economic depression and there were few jobs or opportunities for young men. The war supplied both.

Unlike Ernie, who had spent nearly fifteen years training at the Minto Barracks, most of the new recruits received little training in the use of the more intricate guns or had even learned how to prime a hand grenade. One private, in The Canadians at War: Vol. I, p. 126, says"I had exactly 30 days training. I learned how to left turn, how to right turn, how to salute -- all the usual things. But I never fired a shot till I got to Hong Kong." In order to prepare the Grenadiers for battle readiness and for the tropical climate of Hong Kong, they were sent to Jamaica. The Grenadiers did not actually know where they were to be sent. Most thought that it might be to India.

Ernie in Jamaica

Ernie records that he arrived in Jamaica on June 21, 1940 and left on September 13, 1941. Unfortunately, he kept no written diary but he took many photos which give some idea of how this young man from Winnipeg reacted to tropical Jamaica.

There are pictures of Ernie and his buddies posing proudly in their uniforms against a background of tropical foliage with a look of happiness and excitement in their eyes. There they were: far from the prairies with steady incomes and a sense of purpose to their lives. There are also many photos of tourist sites such as the dwelling place of Horatio Nelson, as well as pictures of an elaborate parade. Included is a truly impressive collection of local bars such as Shanghai Lil's, Dirty Dick's, and Happy Joe's: places perhaps Ernie drank his Blue Niles. He told his sons that this was his favourite drink in Jamaica.

Ernie in Jamaica

He arrived back in Canada on September 26, 1941. Irene must have been glad to see him after more than a year away. His two sons would have grown and changed. Sydney was now seven and Spencer was six years old. We can only imagine Irene's feelings of dread, knowing that Ernie was soon to leave again. But she probably also felt pride in the patriotism of her young officer husband. Her family, as well as Ernie's had come from England and it was England and her Empire that this war threatened.

Farewell Photo: Irene, Spence, Ernie, Sydney (L-R)

On October 25, 1941, Ernie and the rest of the Winnipeg Grenadiers left by train for Vancouver where they went aboard the Awatea and the Prince Robert. The officers and 109 men were on the Prince Robert but nearly 2000 soldiers were on the Awatea built to hold only 540 passengers. "Conditions aboard ship were so bad that some of the soldiers mutinied .... almost 50 men managed to desert by the time the Awatea weighed anchor" (Brian and Terrance McKenna, The Valour and the Horror, p. 11). Mutiny was not the only bad omen. Because of administrative bungling in Ottawa, the battlion's 212 trucks, jeeps, and Bren gun carriers still sat on a railway siding in Ontario when the troops sailed from Vancouver. A week later, the equipment was loaded onto an American freighter but never reached the Canadians. It ended up in the Philippines where it was captured by the Japanese. (Brian and Terrance McKenna, The Valour and the Horror, p. 11).

The odds were beginning to mount against Ernie and his fellow Grenadiers. He had been diligent for years -- training as a gunner and an officer -- but this would not be enough in the battle to come. The incompetent military and political adminstrators were sending many poorly trained men without proper equipment to fight a seasoned Japanese army. Apparently the Canadian 'brass' also did not know of Winston Churchill's memo of January 7, 1941:

"If Japan goes to war with us, there is not the slightest chance of holding Hong Kong or relieving it. It is most unwise to increase the loss we shall suffer there".

The man chosen to lead the Canadians in Hong Kong was Colonel John Lawson, who had said that the Canadian troops were not ready for combat. This brave and good officer was to die early in the battle for Hong Kong.

On November 2, 1941, the Canadians reached Hawaii, where ironically they docked beside a Japanese ship (Oliver Lindsay's The Lasting Honour, p.11). The men were not allowed to leave the ship and their identity was to be kept secret. That evening after the ship set out, the officers announced that their destination was Hong Kong.

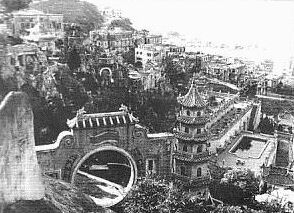

But on November 16, 1941, when Ernie and the Winnipeg Grenadiers entered the beautiful harbour of Hong Kong, they had no idea of the ordeal ahead. After what must have been a difficult voyage in the overcrowded ship, the men saw before them the lovely green hills and below those hills the city of Hong Kong. To these young men from the prairies, the scene looked wonderful: the lush green hills surrounded the Chinese city and small junks moved everywhere in the harbour. What expectations of exotic adventure filled their heads as they debarked from the crowded ships!

Pre-War Hong Kong

Pre-War Hong Kong

Hong Kong was a British Colony consisting of a mainland peninsula called Kowloon and Hong Kong island. This hilly island has a pass through the middle: the Wong Nei Chong Gap. This bit of the island's geography was to play a decisive part in Ernie's life. There is also a large mainland area to the north called the New Territories and several other small islands. Altogether this colony covered 400 square miles.

Hong Kong was ruled by the British but it was really a Chinese city. Twenty thousand British [and a few other Europeans] were surrounded by one and a half million Chinese. Many of the British considered the Chinese inferior to themselves no matter how educated or wealthy these Chinese might be. But most of the Chinese were desparately poor.

As the Canadians marched down Nathan Road to Sham Shui Po Barracks, the street scene looked exotic. It was nothing like Winnipeg. They saw a mix of poverty and affluence. White men in white suits and pith helmuts were pulled in rickshaws by nearly naked sweating coolies. Wealthy Chinese in colourful long robes, beautiful Chinese and Eurasian girls were everywhere. The street stalls and shops were filled with foods the Canadian boys had never seen before. There were also beggars with fly-covered sores and of course great crowds of poor Chinese men and women. It smelled different from Winnipeg too! According to Ike Frisen, a young recruit from Winnipeg, these young Canadian men went out to have a good time: "For the green young Canadians, the first three weeks in Hong Kong were a hoot. We were out for a good time. The pubs were good. The night life was fast. The girls were nice. The night life in Sham Shui Po could show Canada a few tricks. We had a ball." (Ike Friesen in Brian and Terrance McKenna, The Valour and the Horror, p.19).

William Allister (Cdn. Signalman) records a very different impression in his diary: Our first shocker was seeing crowds following the ship in sampans, eating garbage we threw overboard. The waterfront stench made it almost impossible to breathe. ..... The filth, poverty and verminous atmosphere hung over us like a pall. ..... Barefooted old women bent low under huge loads while coolie bosses bellowed behind them. We saw filthy shops and slabs of meat black with flies; harmless beggars their diseased legs half eaten away; white men in Panama hats riding in rickshaws right out of a Hollywood movie. Neon in Chinese ..... a weird sensation." (The Canadians at War: Volume 1, p. 125)

Later in life, Ernie spoke with great respect for those Chinese in Hong Kong. He did not share the attitude of many British officers. One British commander told the Canadian transport drivers: If you're driving down the streets in city of Kowloon, if you hit a Chinaman, you look back in your rearview mirror, and if he's still kicking, you back that truck up and run over him again. Because if you send him to the hospital, it'll cost you the hospital bill. If you kill him, it'll cost you five dollars for burial. (Ike Friesen in Brian and Terrance McKenna, The Valour and the Horror, p.19).

Even driving in Hong Kong was different from Winnipeg. According to the story that Ernie told, driving in Hong Kong was hazardous because the Chinese had a habit of suddenly crossing the road in front of an oncoming vehicle. He said this was to kill off any devils that were following the Chinese person.

The British rulers of Hong Kong continued their lives of placid indifference to the Japanese across the border in China. But the soldiers, including the Winnipeg Grenadiers, worked at building defenses such as machine gun emplacements and a chain of pill-boxes, and improving the wiring on the island for communications. British General Maltby was in charge of the forces in Hong Kong. He was an experienced soldier in his fifties and he was worried about the soldiers' fighting ability. He relied upon British intelligence reports which said that there were 5000 poorly trained and equipped Japanese across the border in China.

On December 3, General Maltby and Brigadier Lawson (who had been appointed to command the brigade on the island) toured the frontier together and looked at the Japanese through binoculars. The Japanese looked scruffy, indolent, and uninterested (Oliver Lindsay, The Lasting Honour, p.24). Other reports from China told of many more Japanese troops and of an imminent invasion of Hong Kong but Maltby did not believe these reports. Many in Hong Kong believed it was the other way around and that the Japanese feared an attack by the British from Hong Kong!

If there ever was an attack by the Japanese, the British expected it to come by sea. So the guns were placed in the south of the island facing into the South China Sea. But there was a series of concrete bunkers, tunnels, and trenches built in the 1930's to protect the water reservoir in Kowloon. It was called the Gin Drinkers' Line and was believed to be quite capable of repelling any attack from China should anyone really be foolish enough to try it.

The Chinese civilians were not deluded like the British. There were many amongst them who had fled China before the advancing Japanese. They knew the strength of those cruel and terrible soldiers.

The British civilians still did not worry. One executive of a bank refused to allow his employees to be mobilized: "The bank would have to close! There is no war sir, and never will be". Residents of The Peak chased off soldiers trying to dig trenches because they might trample on the flower beds (Ted Ferguson, Desperate Siege: The Battle of Hong Kong, p. 32-33).

On Sunday, December 7, Japanese troop movements were spotted and General Maltby was told as he attended a Church of England service. The officer said that 20,000 Japanese were on the move. "They must be exaggerating" said Maltby. But Maltby left the service and by afternoon, every soldier and volunteer was at his post.

Amongst Ernie's papers is an Order of the Day, dated 8 Dec. 41 and is signed by R. Brook-Popham, Air Chief Marshall, Commander-in-Charge, Far East. The letter is long but these few paragraphs convey the tone:

Japan's action today gives a signal for the Empire and the Naval, Army, and Air Forces and those of their allies to go into action with a common aim and common ideals. We are ready. We have had plenty of warning and our preparations are made and tested. We do not forget .... the petty insults and insolences inflicted on us by the Japanese in the Far East. We know these things were done because Japan thought she could take advantage of our supposed weakness .... She will find she has made a grievous mistake. We are confident.....we have one aim and one only. It is to defend our territories .... Then will come the time to attack so as to cripple forever the power of the enemy to endanger our ideals, our possessions and our peace. What of the enemy? We see before us a Japan drained for years by the exhausting claims of her wanton onslaught on China. Let us all remember that we here in the Far East form part of a great campaign for the preservation in the world of truth and justice .... while from the civilian population we expect patience, endurance, and serenity .... which will go far to assist the fighting men to gain final and complete victory.

In spite of the Air Chief Marshall's confidience, on the same day, December 8, the Japanese destroyed every airplane at Kai Tak airport in a matter of minutes. The British had watched some planes approach and presumed them to be their own before they saw the Japanese insignia. William Allister writes: On the morning of Dec. 8th ..... some of us were shaving when we heard air raid sirens. We paid no attention. "The usual rehearsal" my diary says. We heard this booming and figured it was artillery practice. Jenkins went out on the balcony to look ..... "They're dropping bombs" he said. We just laughed. We nearly died laughing as the windows were blown in! (Oliver Lindsay, The Lasting Honour, p. 37.)

The war had begun for Ernie and the Winnipeg Grenadiers.