Introduction - Cory Turner (daughter)

In the dark days of the Second World War, the British deemed Hong Kong expendable and decided not to reinforce its garrison. However, Canada agreed to send 1975 men of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, the Royal Rifles Of Canada and 'C' Force Headquarters, even though their training was incomplete and their military experience consisted mostly of garrison training. Ready or not, they became the first Canadian troops to fight as a unit in the Second World War. More than 550 did not come home. They reached Hong Kong on November 16th and the Japanese attack came on December 8th, the same morning as the attack on Pearl Harbour. The invading force was overwhelming, with heavy artillery and air support. The defenders, with no hope of relief or resupply, held out for 17 ½ days, during which 290 Canadians were killed and 492 wounded. The survivors were imprisoned in foul conditions in Hong Kong, where another 129 died. In 1943, most of those still on their feet were sent as forced labourers to Japan, where about 135 died.

Here is the story of one of the survivors, a hero, my Dad.

My Time in Hell

It all started when the Governor of Hong Kong surrendered the Island to the Japanese, in order to save the civilian population. We were ordered to lay down our arms and cease fighting. Had we known what we were going to endure over the next 44 months, I am sure most of us would have fought to the finish and taken some more of the enemy with us. At this time we received some rations and I recall saying bitterly “we have to lose the war to get something to eat”. Meals had been very sporadic during the fighting.

With dismay I looked around and saw some of my fellow soldiers break down sobbing. I will never forget that Christmas. After a few days we were taken back over to Kowloon, on the mainland, and marched down the main street. I was feeling defeated and humiliated as the civilians silently stared at us. A few short weeks before we had marched down the same street, with bands playing, flags waving and people cheering, because we were there to protect them. We failed.

We were taken to Shamshuipo barracks, which the Chinese had completely looted, taking everything movable, including windows, doors, beds and bedding, leaving us with the bare cement walls and floors. This was where we were to spend the next few months, sleeping on cement floors. It was a dismal looking place. To add insult to injury the Japanese were calling us cowards for surrendering, as they would commit hari-kari before they would surrender. We had no choice - we were vastly out numbered and out gunned.

Rumour had us believing this was to be a short-term situation,as Chang - Kai - Shek and other Forces were on their way to release us. This was not to be. We were to spend the next 44 months in cruel and inhuman captivity.

We were fed a small portion of rice twice a day; needless to say it was not long before the men grew weak and sick. I remember when I wanted to stand up I had to do it by degrees or I would black out. I was not the only one. When one of the men died the mournful and haunting notes of the Last Post could be heard by all in camp. This practice had to be stopped as it was too demoralizing. Afterwards the Japanese simply took the bodies out of camp. To this day the playing of Taps has a very strong emotional effect on me. We were desperate for food. I was angered and disappointed when a friend of mine told me they caught a stray dog, cooked it and ate it. He could not find me to share it with them.

The cruelty of the Japanese was always evident – they took every opportunity to ridicule or strike out at the prisoners. One of the cruelest was an interpreter we called the Kamloops Kid. He had been raised in Kamloops BC and apparently resented the way he had been treated there. One day we were all lined up for roll call and our Quarter Master was trying to get some shoes for the men who were on the work party. The Kamloops Kid backhanded the officer across the face, knocked him to the ground and beat him until he drew blood. The officer was totally humiliated in front of his men. The Kamloops Kid carried out this type of vicious attack and even worse all the time. Another time the guards seized a young Chinese girl, stripped her naked, tied her to one of the fence posts, poured buckets of cold water over her and stood around and laughed. If any of the prisoners or civilians got close to the fence they were beaten. One of our guards was a man who used to come into the camp to sell us ice cream before the Japanese attacked us.

After a few months in this camp most of the Canadians were taken back over to the island of Hong Kong and imprisoned in an old refugee camp called North Point. Here the Japanese continued their cruel treatment of the prisoners. One of their more disgraceful taunts was to throw a lit cigarette butt on the ground and when one of our desperate smokers went to pick it up the guard would put his foot on it and grind it into the ground. I was glad I wasn’t a smoker, however when I could gather a butt, I did and passed it on to one of the guys.

One day when a Chinese civilian walked too close to the barbed wire fence the guards beat him unmercifully and when they tired of this they bayoneted him in the stomach and threw him in the harbour. This was sport to them and it was evident they enjoyed it.

One day the guards took a work party of prisoners out to the hills to collect the bodies of the soldiers. They were brought to a field across from our camp, piled up like cord wood, doused with gasoline and set on fire. That’s when I knew there truly was Hell on earth. I learned from one of the guys on the work party that the body of my good young friend, Kenny Simpson, had been found, identified only by his striking blond hair. At that time it was like a punch in the stomach, but in the following years I often thought he was one of the lucky ones. After the war, being a friend of his family I went to tell them what I knew about Kenny’s death. It was a very painful task. He was just a kid.

The huts were a bit better at this camp but the rations were still small and the constant hunger continued to weaken us. One day the men in our hut decided that the staff sergeant serving our ration of rice was doing a poor job of it and requested that one of the men take over the task, feeling that he could get the portions more even - this was extremely important to starving men. He refused, called the duty officer, who sent the rice back to the kitchen. About 45 men went to bed that night hungrier than usual. Needless to say if we had had to go back into action with this staff sergeant and officer, they would never have made it out alive. From then on we hated them just about as much as we hated the Japanese.

Dysentery and diarrhea were common ailments and to make matters worse there was an outbreak of diphtheria. There was no serum for the prisoners and many died of this disease. Athlete’s foot and foot rot were common ailments as well - it seemed to help if I urinated on my own feet.

Our hut was located close to where the sick men were and most nights I could hear the cries and moans as the men suffered with little or no medical help. Many died of dysentery during this time. One of the worst jobs I had was emptying the dysentery buckets. The stench was almost unbearable, something I will never forget.

While at this camp, I spent a month working on extending the runway at Kai Tak airport. It was back breaking and tiring work using pick and shovel and carrying the rubble away in wicker baskets, coolie style. Constant hunger made the work even more difficult. If you did not move fast enough there were the ever present rifles butts and 4 foot staffs to prod you on.

Around this time it was decide to weigh us. I weighed 125 pounds. Shortly after this I contracted diphtheria and went down from there, earning me the nickname of Bone Yard.

One rainy night three of our guys, having had enough of the cruel treatment, decided to try to escape. They had not gotten very far when the guards caught them. They were beaten and then killed. From then on we were divided into groups of ten and told if one escaped the other nine would be shot. We believed them, because by this time we knew the Japs were capable of anything.

The Japs electrified the barbed wire fence and the first casualty was the guard’s dog. We were secretly amused by this, certainly not over the death of a dog, but because something had gone wrong for the Japs for a change. Obviously the Japs weren’t amused as that night we were all hauled out of bed and made to stand in the pouring rain for a couple of hours while they screamed, raved and threatened us. The next night the process was repeated, again in the pouring rain. Overcome with weakness I collapsed and shortly after ended up in the hospital with diphtheria. By this time I could no longer swallow any food. I also had a large ulcer on the top of my left foot. A friend of mine, Bill Nicholson, scrounged some sugar from the Officer’s Mess and I was able to suck on it and get it down. This helped to keep me alive. When we reached the hospital I was too weak and sick to walk up the stairs. I was put on a stretcher and carried up two flights of stairs to the Diphtheria Ward. When the doctor looked at me I heard him say “why in hell don’t they send them up here in time?” I said to myself “I am in time, the bastards are not going to get me”. That became my mantra to help me get through the ensuing years. As there was no serum available the only treatment was to gargle several times a day with permanganate, a form of salt. The food I was able to get down would not stay down as my stomach was in such bad shape. Charcoal and water helped me. This treatment worked for some of us, many just died.

A few days later a guy, Bill Harkness, was moved in beside me. He was in pretty bad shape. I was talking to him and he said to me “I may as well pack it in and join my good friend Chapman out in Boot Hill (his words for the graveyard). I told him to hang on, that he had a chance to pull through, but he was quite adamant about joining Chapman, so I asked him if I could have his boots if he died. In the morning I had his boots.

Even at the hospital the cruelty of the guards was evident. I recall watching a little old Chinese lady gathering firewood, close to the hospital. For no reason, other than their amusement the guards set their guard dog on her and chased her off, terrified and screaming. The Jap guards stood around and laughed. I felt helpless.

One day the Americans conducted a small air raid near the hospital. The Japs unsuccessfully fired at them. I guess we couldn’t keep the look of satisfaction off our faces, and we paid for that. We were lined up and made to stand at attention while a Jap officer yelled, raged and, as always, threatened us, all the time waving his sword in front of our faces. I had a very swollen face due to a badly infected tooth. The Jap officer stopped in front of me and suddenly backhanded me as hard as he could across my swollen face. I did not flinch, but looked him straight in the eye with all the hate I could muster, and under my breath, I called him all the vile names that came to mind all the time thinking, the bastards aren’t going to get me!

I was on the balcony of the hospital and I saw the Japs bringing in some more sick prisoners. I recognized one of them. It was my close friend Wint Fox - he was being led as he was half blind and he looked to me like a wizened up old man. It was one of the saddest sights I have ever seen. Later on I tried to get to see him, but the guards would not allow it. I did not get to see him until we returned home about three years later. I did not know if he was dead or alive during that time.

A few days later I was taken back to Camp Shamshuipo, where I was allowed to work in the Dip. Ward. It was assumed that I was immune, as I had already had diphtheria. While we were there we did all we could to help the patients, which wasn’t much.

In August of 19421. the Japs sent 500 of us to Japan to work in their shipyards and mines. We were put on a ship, down in the hold, where we didn’t have any fresh air and where there was not enough room for all of us to lie down at the same time. We were fed sparingly and not allowed on deck. It took a few days to get to Japan. We were hungry, dirty and we stunk when we reached Nagasaki. When we finally came up on deck the Japs held their noses because of the smell. After we docked we were put on a blacked out train and taken north. Along with approximately 200 other prisoners, I was taken to the Nippon Kokan Shipyards where, over the next 27 months, we were forced to work. I was put to work over open forges shaping keel plates etc. with heavy hammers. It was gruelling work, without even taking into consideration the condition I was in.

Every morning we were lined up and had to count off in Japanese. If we made a mistake we were either backhanded across the face or hit with a staff or rifle butt. This was a horrible and cruel way to start the day. We were then marched (sometimes in the Jap’s style of a German Goose Step, another form of humiliation) to the shipyard. This took about 15 to 20 minutes, in all kinds of weather. We often arrived at work soaking wet but were put right to work. We had no gloves or safety gear.

On the way over to Japan the Japs had taken away my boots and had given me a pair of old canvas shoes; these did not last long around the forges. I remember having to tie 2 Japanese straw sandals on each foot to fit the size of my feet, which wasn’t a great solution but it was the best I could do. I finally took my chances and made a stand. After suffering much verbal abuse and threats of disgusting duties such as cleaning the benjos (outhouses) with my bare hands I was given a pair of boots. The first day I wore them to work some of the Jap workers kicked me in the ankles and swore at me. If I had kicked them back I would have been beaten. I just suffered more humiliation at the hands of the Japanese.

Another despicable form of enjoyment for the Japs was, in order to punish one of the prisoners, they would put some water in a bucket and make him hold it shoulder high straight out in front of him. If his arms sagged too much he was whacked with the staff several times.

Some time later I developed Beri Beri, pellagra and with the constant diarrhea, plus the starvation diet I was no longer strong enough to swing the big hammers. I was sent to “lighter work” delivering the keel plates and other heavy material to where the ships were being built. This material was loaded on 4 wheeled pushcarts, which we had to manually push down to the ships. One day when the cart ahead of us was unloading heavy plank hold covers, the cable broke, the load fell and to our horror crushed one of our men to death. It was just one more tragedy in this living nightmare.

The heavy work pushing the cars was not compatible with my loose bowels and I had to make many a frantic dash to the benjo (outhouse). One cold day I didn’t quite make it. Fortunately my friend, Bill Nicholson, happened to be passing by and he found some old sacking for me to clean up with. There was no soap and water. It was another example of this life’s indignities. We helped each other all we could.

Later on down the road I had more to be thankful to Bill for, as he was the one who introduced me to my beautiful beloved wife.

Back in camp it was a living nightmare as well. We slept and lived side by side on platforms about 16 inches above a packed dirt floor. The platforms were covered with a thin straw matting, a great place for vermin. A few men used to pick the body lice off themselves and eat them, in order to quell the constant hunger. We learned a lot about hunger. We learned that it robs you of all other thoughts and feelings. We learned that hunger doesn’t go away. The only exception to this was if you were sick you weren’t as hungry so sometimes I didn’t mind being sick.

Some of the men had dry Beri Beri so bad they would sit up most of the night with their feet in cold water moaning with pain. It was like having hundreds of small knives sticking in the bottom of your feet. We called them Electric Feet. In the night I would often hear someone rushing down the hut trying to make the benjo in time and the curses when they didn’t. At least there was cold water to clean up with, the floor didn’t matter, it was just dirt anyway.

I slept next to the outside wall and often a rat would lie across my feet (for the warmth I guess). One night I woke with a start, a rat was nibbling at my ear. I smashed him against the wall and he left in a hurry.

Often the guards would get us up in the night for no reason at all, just another form of torment. We were constantly told that if the Americans landed in Japan all the prisoners would be killed.

When one of the men died he was put in a wooden box and placed at the top end of the hut. The Japs put a few trinkets on top of the box and a day or so later a priest of some kind came and rang a few bells, chanted something (a Japanese custom, I presume) then hauled the body away on a bicycle trailer. This was stopped as it demoralized the men even further. After that the body was simply put in the Jap’s bathhouse, a few cookies put on top of the box and hauled away the next day.

One day I was on the detail to carry the body to the bicycle when our Sergeant Major opened the door to the bathhouse and said, ”who stole the dead man’s cookies?” Starving men will do just about anything.

One Christmas some Red Cross parcels arrived and we got what was left after the Japs took what they wanted. They gave them out, (for example 3 parcels for 7 men) and left it up to us to divide them evenly. It was more frustration for starving men and more torment from the Japs.

Once we were given something called tooth powder, it was just like pink chalk, and as I was using charcoal to clean my teeth, I used mine on my rice, hopefully to give it some flavour and help me fill up. It didn’t work. Often there were weevils and small bugs in our rice, we ate it anyway and called the bugs fresh meat. I had managed to keep a Dr. West toothbrush, one that I had obtained from one of the houses, during the fighting. It lasted me the whole time in prison camp.

Personal hygiene was almost non-existent. I had no soap, a small piece of cloth to use as a towel and of course no hot water. After 6 weeks of physical labor around a hot forge, we were offered a rare treat, a bath. The down side was that we were last in line after the Japs and about 150 other prisoners. When we got there it was like pouring lukewarm muddy water over your body. Were we cleaner or dirtier? We couldn’t decide. This so called bath was allowed every few weeks, the filthiness of the water depended on where you were in line.

One night the Americans bombed all around our camp and started huge fires. We found out later they had burnt out about 4 square miles. We were secretly elated. When the bombing started the guards got us out of bed and made us carry bags of rice from their storeroom to an air raid shelter (one we were forced to build, but were never sheltered in). I was carrying a bag that conveniently had a small hole in it and some leaked out. A few of us took a handful and were eating raw rice; the guard caught us and gave each of us a few whacks with his staff. That ended our extra rations. When the raid was over we had to return the rice to the storeroom. We worked half the night but still had to go to the shipyard in the morning.

Just when we thought things couldn’t get any worse, they did. A group of us were moved into the mountains to work in the coal mines. When we arrived at the mines we were lined up in the open and made to strip naked, with all our belongings on the ground in front of us. The Japs picked through our meager gear and took what they fancied. This operation was carried out in full view of the people from the nearby village who stood on the hillside and stared at us. We stood there, naked and humiliated, and could do nothing about it.

Most of us were skin and bone; we could count each other’s ribs and were nearing the end of our rope when we were sent down the mine to work. Even the most optimistic of us knew we couldn’t last another winter. Every day on our way to the mine we had to stop, stand to attention facing Mount Fuji and bow while the guards said a prayer to their Gods. We had the satisfaction of cursing their idols, under our breath. It helped a bit.

My first job in the mine was digging a tunnel in the rock by blasting and digging with pick and shovel. It was hard and exhausting work. One day one of our gang was “losing it” and not working hard enough and our foreman (a guard we called Red Eye) was beating him unmercifully with his staff, the poor guy was cowering on the floor and the guard kept hitting him. I could stand it no longer, I grabbed the guard, threw him against the rock wall, and placed his staff across his throat and began to choke him. I nearly killed him, but I cooled down a bit and let him go. It was a very tense moment. He was too frightened to retaliate then but I figured when we got up top I would get the beating of my life, if not worse. Nothing happened. Then I thought I would get a brutal beating in the morning when I reported for work. Nothing happened. I finally realized he didn’t want to lose face in front of his superiors for not being able to control a prisoner. He got even with me. From then on he gave me the hardest and most risky jobs. We used to drill a series of holes in the rock wall, fill them with dynamite, lay in the fuses, light them and run around the corner away from the blast and count the number of explosions to make sure all the charges had gone off. Most of the time our count was 1 or 2 short. One of us had to go in, pull the dud charges, and hope they didn’t go off while we were in there. After my attack on the guard that job became my sole responsibility. It was a life threatening chore. Any drilling or jack hammering above the head also fell to me as one of Red Eye’s retaliatory jobs. In the condition I was in it was extremely hard work, close to impossible. He finally found the perfect way to even the score. He sent me down to the coal face to work, which was like being sent to the bowels of Hell. We went through a small door to get down to the coalface, outside of which were 2 benjo buckets and a pool of sulphuric water. We used to get in this pool to get the sweat and coal dust off our bodies after we finished work. It was the only way we had to try to clean up a bit; the smell in this area was awful.

We worked in well over 100 degrees of heat, naked except for a small thin cotton Japanese style loincloth and a carbide light, fixed to a cloth cap. Again there were no hard hats, gloves or any safety equipment of any kind. We had to stay down the mine until we had filled and sent to the surface our quota of coal cars. It was the hardest and most trying time of my life. Around this time I was still suffering with diarrhea, I had boils under each arm and was coughing up worms. I was very down. When we filled a car it was sent to the top, hooked to a cable. It often jumped the tracks and we had to man handle it back on the track using heavy timbers as pry bars. There was always a roll back when the cable took up the slack. I was so exhausted and desperate to get out of the mines, that I planned to place my hand under the wheel and take part of a couple of fingers off. I knew that would get me out of the mine, but at the last second I pulled my hand away, feeling that was the coward’s way out. Thus I endured 4 months down the mine.

I was exhausted, sick and almost out of hope and at his time, to my horror, the thought crept into my mind, that you or I would kill his own mother to get out of this place. I am still filled with shame at such an ugly thought.

One morning I had been throwing up worms again and was feeling low at the thought of going down the mine again. One of the men came up to me and said, “I think the war must be over – the guards are all gone”. Apparently they had taken off during the night. I said thank God and went back to my sleeping mat, ate my noon binto (a small box of rice) that we usually took down the mine with us. I just lay back and said “the bastards didn’t get me after all” and I realized I didn’t have to go down the mine anymore. I later learned that I had worked in the mine one shift after the war had ended – it rankled me to say the least. I did have one small triumph over the Japanese – I had with me a gold onyx ring my mother had given me and as the Japs were stripping us of anything of value I hid it in the pleat of my uniform pocket, my friends hid in the sick bay, and I buried it in various places over the years. I brought it home!

The last time I saw my old nemesis, Red Eye, one of the Peterson boys was chasing him down the track. I never did find out if he caught him or not, I hope he did. If any one of us had caught any of the guards we would have happily broken every bone in their body.

After awhile some of us went outside the camp and gathered up a few of the farmer’s chickens, dug up some vegetables and cooked ourselves a feast. Later on we gathered up some good size rocks and printed out P.O.W. on the hillside as a marker, so the planes could find us. A day or so later the American Navy planes found us and put on quite a show. We were ecstatic, after 44 long and horrific months we finally had contact with friends. Shortly after the larger planes came over and dropped food and medical supplies. Knowing the condition of my stomach I lived on canned peaches for a few days - they tasted like the nectar of the gods.

Later I was saddened to hear that 4 of the guys had decided to celebrate their liberation by drinking anti-freeze, all 4 died. To have endured what we had and to die before they got home – what a tragic waste. It was four more lives lost in this hellhole.

Tragedy hadn’t finished with us yet. It was an overcast day and one of the planes came in so low we could see them waving at us. One of the crew took off his jacket and threw it down to us. A few moments after they passed over us we heard a loud explosion and saw a large ball of fire. The plane had crashed into the nearby mountain and all aboard were killed. It’s still etched in my mind. What a terrible ending for doing a good deed. I didn’t know any of the crew but I will never forget them.

A short time later the Americans sent in a train to take us out. All the way to Tokyo harbour the train was escorted by U.S. planes. It sure gave us a feeling of security, something we hadn’t had for many months. When we arrived at the American base near the docks, we threw away our lice ridden clothes and were put through de-lousing showers. We were then broken into small groups and taken aboard their ships in Tokyo Bay. I was fortunate to be put on board the battleship Iowa. It felt like a floating hotel to me. The Americans were very kind to us, they gave us anything we wanted or they thought we might want. They would not let us carry our gear or lift a finger.

We were given a medical examination and when I appeared before the medical officer, he took one look at my emaciated body and said, “How in God’s name did you ever work in a coal mine?” I replied, “if you wanted to eat and live, you worked.”

One day a British officer came on board to pay us some of our back pay. He had a desk set up on deck and with his assistants and flanking armed M.P.s he set out to pay us in fine British military style. We were a rag tag looking lot, but we had to march up to the desk, salute, sign for our pay, salute again, about face and march off. When we looked at our pay it was in the huge amount of 5 dollars. I wonder why he bothered. There was no way the Americans would accept it in their canteens. To us everything was free. One of my best memories of my time spent on the Iowa was going up on deck late at night or in the morning before sunrise, drinking coffee, and talking to the night watch. We just talked about things in general, nothing heavy. What a nice change from the previous 44 months. Imagine feeling grateful for being treated like a human being.

From the Iowa I was flown to Guam, where I spent a week or so getting de-wormed and receiving other medical attention. When I left the hospital my appearance had improved. I looked almost human again.

It was quite a contrast to arrive back in Canada and to be expected to act like soldiers when some of us had been prisoners longer than we had been soldiers.

However – we were home!

We were given the usual medical and leave, and then told to forget about it and get on with our lives. Which we did as best we could. It had been a long and horrific ordeal, 1,232 days in captivity, starving, in deplorable, abusive conditions, and to this day I find it hard to express the feelings of years of hopelessness, helplessness and humiliation. When asked what it was like I just said, “you had to be there”.

We came home to learn the whole exercise, dreamed up by Churchill and MacKenzie King was just a “futile gesture”. They knew if the Japanese attacked Hong Kong it could not be held, but they thought a show of force might deter the Japs from attacking. What a cruel joke to play on 2000 young Canadian soldiers.

Now, after 60 years it still haunts me. It plays over and over in my head like the real life horror movie it was. But – I won’t let the bastards get me.

1 No Canadians were part of the early drafts to Japan, so it is likely that Mr. Johnson was on the January 1943 draft, which was the first draft that included Canadians.

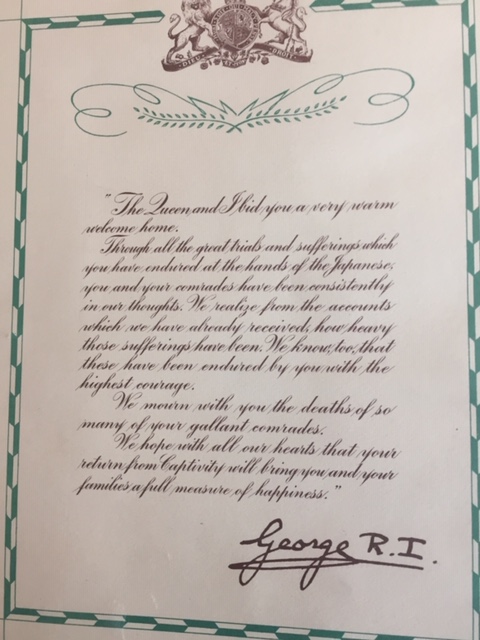

Image Gallery

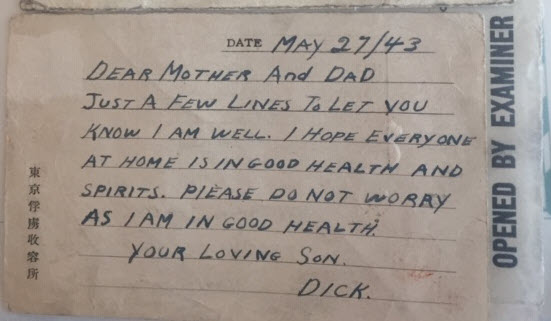

POW Letter - May 1943

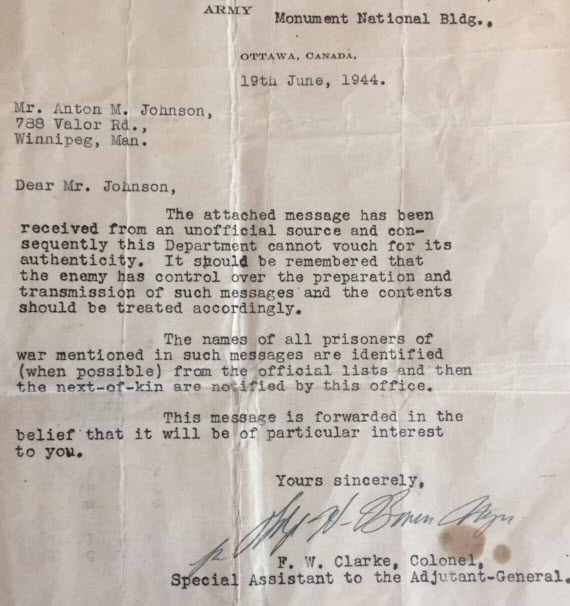

Official Letter Regarding POW Message

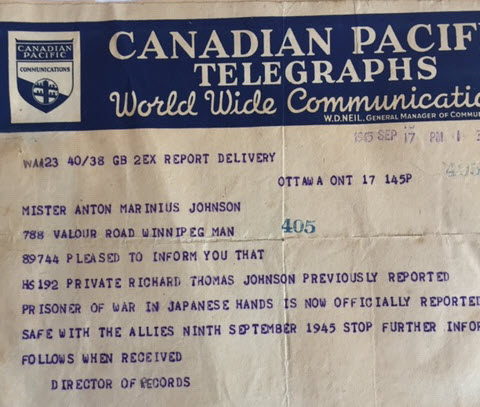

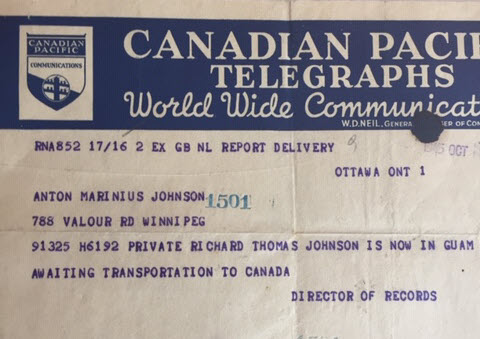

Telegram - Reporting Safe with Allies

Telegram - Reporting Awaiting Transportation Home