1st Bn The Royal Rifles of Canada

General Information |

||

| Rank: | First Name: | Second Name: |

|---|---|---|

| Rifleman | Robert | Eugene |

| From: | Enlistment Region: | Date of Birth (y-m-d): |

| Fredericton NB | Eastern Quebec | 1924-06-07 |

| Appointment: | Company: | Platoon: |

| HQ Coy | ||

Transportation - Home Base to Hong Kong

Members of 'C' Force from the East travelled across Canada by CNR troop train, picking up reinforcements enroute. Stops included Valcartier, Montreal, Ottawa, Armstrong ON, Capreol ON, Winnipeg, Melville SK, Saskatoon, Edmonton, Jasper, and Vancouver, arriving in Vancouver on Oct 27 at 0800 hrs.

The Winnipeg Grenadiers and the local soldiers that were with Brigade Headquarters from Winnipeg to BC travelled on a CPR train to Vancouver.

All members embarked from Vancouver on the ships AWATEA and PRINCE ROBERT. AWATEA was a New Zealand Liner and the PRINCE ROBERT was a converted cruiser. "C" Company of the Rifles was assigned to the PRINCE ROBERT, everyone else boarded the AWATEA. The ships sailed from Vancouver on Oct 27th and arrived in Hong Kong on November 16th, having made brief stops enroute at Honolulu and Manila.

Equipment earmarked for 'C' Force use was loaded on the ship DON JOSE, but would never reach Hong Kong as it was rerouted to Manila when hostilities commenced.

On arrival, all troops were quartered at Nanking Barracks, Sham Shui Po Camp, in Kowloon.

Battle Information

We do not have specific battle information for this soldier in our online database. For a detailed description of the battle from a Canadian perspective, visit Canadian Participation in the Defense of Hong Kong (published by the Historical Section, Canadian Military Headquarters).

Wounded Information

No wounds recorded.Hospital Information

No record of hospital visits found.POW Camps

| Camp ID | Camp Name | Location | Company | Type of Work | Arrival Date | Departure Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HK-SM-01 | Stanley | Fort Stanley, Hong Kong Island | Capture | 41 Dec 30 | ||

| HK-NP-01 | North Point | North Point, Hong Kong Island | 41 Dec 30 | 42 Sep 26 | ||

| HK-SA-02 | Shamshuipo | Kowloon, Hong Kong | 42 Sep 26 | 45 Sep 10 |

Transportation SE Asia to Home

| Transport Mode | Arrival Destination | Arrival Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| USS Admiral CF Hughes | Victoria, BC | 1945-10-09 | Manila to Victoria BC |

No other or additional related information found. Please submit documents to us using the contact link at the top of this page.

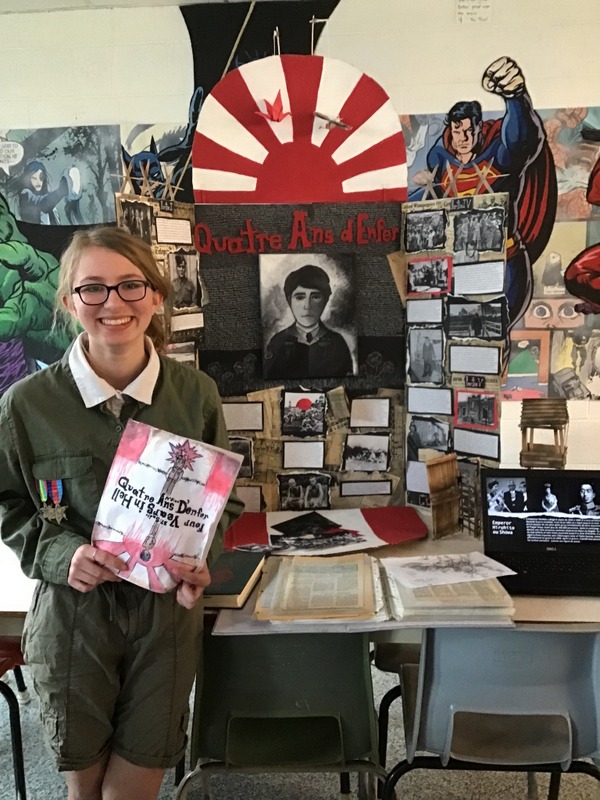

Post-war Photo

No other or additional related information found. Please submit documents to us using the contact link at the top of this page.

Other Military or Public Service

No other or additional related information found. Please submit documents to us using the contact link at the top of this page.

Death and Cemetery Information

| Date of Death (y-m-d) | Cause of Death | Death Class | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1986-04-22 | Post War | ||

| Cemetery Location | Cemetery | Grave Number | Gravestone Marker |

Gravestone Image

No other or additional related information found. Please submit documents to us using the contact link at the top of this page.

Obituary / Life Story

MCGINN-At Dr. Everett Chalmers Hospital on April 22, 1986, Robert E. McGinn of 720 Palmer Street, Fredericton; survived by his wife, Velma B. (Wood) McGinn, three sons, one daughter, eight grandchildren, three brothers, three sisters, several nieces and nephews. Resting at J. A. McAdam Funeral Home, 160 York Street, Fredericton. Visiting hours on Thursday 2-4, 7-9 p.m. Funeral mass will be celebrated at St. Dunstans Church on Friday at 11 a.m. Rev. Joseph Cochrane officiating. Interment will be made in Hermitage Cemetery.

Unknown Newspaper clipping

General Comments

McGinn, Robert Eugene

More than a quarter-century has passed but the horrors, privations and indignities of a Japanese prison camp of World War Two, still linger in the mind of a Fredericton resident.

It all began early in October 1940, when Robert McGinn-now living at 11 Carleton Street tried to join the Canadian army. His buddies had already joined and were training for overseas duty. He was sixteen years old. When his father heard of his son's intentions, young Robert was quickly removed from the military nominal roll.

Robert McGinn had to enlist. He knew he was too young to make it in the provincial capital, so he hiked off to Sussex where he volunteered and was accepted by a Quebec Regiment, the Royal Rifles of Canada. Perhaps if he knew then the terror he was to face, he might have changed his mind. But less than a month later young McGinn was a rifleman, starting training that was to lead eventually to four years of imprisonment on foreign soil. He joined the Canadian Army weighing 160 pounds. He was to reach 176 pounds only to drop later to 120 in less than one week.

From Sussex, after basic rifle training, he moved to Newfoundland, then considered an overseas posting. There training continued with the ancient field and strip Lewis, the Lee Enfield rife and the newly designed British Bren gun.

While in Newfoundland, uniforms and personal equipment for the members of the Canadian Army were not available. Private McGinn and many troopers had to send home for civilian garb to maintain reasonable dignity when appearing before the public. His tour was short in the island colony. After a 13-day stay in Saint John, the entire regiment moved to the Citadel in Quebec; that was in October, 1941.

Then the start of the big fateful jump took place. Robert McGinn and his regiment left Camp Valcartier in October, 1941. On arrival in Vancouver they immediately boarded the troopship that was to bring them closer to four years of torment.

There were about 1900 troops on board the ship, said Mr. McGinn. Besides his own regiment of Royal Rifles, there were soldiers of the Winnipeg Grenadiers. After 21 days on the peaceful Pacific and a colorful but brief stop-over in Honolulu, the young Canadian adventurers marched smartly down the gangplanks onto the island of Hong Kong.

During the sea voyage, heavy clothing issued for the Canadian winter was discarded and the tropical gear given to all hands. When they set foot on the Oriental island in mid-November 1941, it was a far cry from chilblains and red noses of New Brunswick.

Long before the Orient became a fell reality; Mr. McGinn said the Canadian government was saying war would not break out in the Pacific. They were sending a token force to augment the British in Hong Kong, and were sure all would be well. But, said McGinn in an interview recently "Our platoon officer, a Lt. Fry; was betting ten-to-one we would be the first Canadians in action as a regiment." He said the lieutenant was making this prophecy while their train was hurting through the Canadian Rockies.

Lt. Fry died in Hong Kong. "We knew before we got to Vancouver we would be in action..."said Mr. McGinn. He added, "We didn't get official word of our destination until we left Honolulu. Then the brigadier told us that "depending on ourselves", if we ever got back home, we might have to fight our way off the ship because Japan was ready to go to war."

He said "We were roughly two weeks there (in Hong Kong) before the Japanese launched their assault on Pearl Harbor Dec 7, 1941." He said all troops were moved off mainland China to Hong Kong, where battles raged for 18 days before the dramatic surrender.

Of the surrender, Mr. McGinn said, "We fought for 18 days before we were ordered to give up. We were beat anyway. There was no food, the water supply was cut off, and our defence was limited to small arms against the artillery, mortar and aircraft of the enemy. The governor of the island, said Mr.McGinn, surrendered because the enemy threatened to wipe out the civilian population. That was Christmas day; 1941.

During the actual surrender Private McGinn was scouting elsewhere. He, two other Canadians and a Chinese were foraging for food, water and ammunition, they saw a ship rammed on the rocks off shore. "We didn't surrender to the earlier bids of the enemy" he said "because we were told the Japanese didn't take prisoners of war." While the four were making their way to the derelict ship, they were stopped dead in their tracks by a platoon of enemy soldiers. The Japanese were down on a small road on both sides of a small hill in the mountains of the land of Hong Kong. Surrounded, the Canadians smashed their rifles to keep them from enemy hands. Then McGinn ripped his undershirt to make a white flag, and tied it to a sick "We were so scared and excited," said Mr.McGinn, "we didn't walk around the small hill but jumped to the road, a drop of about 25 feet, landing on our feet." To this day he still remembers the landing. It sure stung..." "They (the enemy) wanted to know who we were and when we said Canadian, they couldn't figure out what the Canadians were doing there. They expected only British and Americans." He said the officer in charge of the enemy platoon spoke some English, enough for us to understand him. He said the Japanese were "as confused as we were."

There the formalities ended. The New Brunswick soldier and his buddies were "put to work burying the dead. But," he added, "we didn't bury them, we threw them over the side of the cliff, and the bodies landed about 200 feet below." He explained that the location was the side of a mountain, and the bodies- some of which were dead for more than a week in the sweltering sun-were heaved to continue decomposition far below. The dead were Canadian, British, Japanese, Chinese and Indian; "about 100 bodies," he said.

After the gruesome task was completed, the Japanese tied their prisoners hands high behind them-near the neck-with barbed wire Mr. McGinn recounted. "It was extremely difficult to board the trucks were were ordered to get on because of the position of our arms, and the pain of the wire. But with a bayonet jabbing behind, we made it."

The barbed wire manacles stayed in place overnight and were only removed the next day. Diseases spread and discomforts were piled on discomforts.

Working on an airport was the main task of Mr.McGinn and his friends. He said "One end of the airport was the water-front and the other was at the base of a mountain. We had to move that mountain with pick and shovel." He said, "During the winter months we never saw daylight in the prison camp. We left it at 6 o'clock in the morning and got back at eight o'clock at night." Still the menu consisted of rice and boiled seaweed. Occasionally", said the veteran, "there was something special, fishheads and entrals." "All this time," said Mr. McGinn, "the men kept going down the hill." When he was taken prisoner, he weighted 176 pounds, but soon overtaken with malaria and dysentry, he had wasted to a mere 120 pounds... all lost within a week. One of the most horrible and continuing discomforts was an "unknown" disease the troops called "hot feet". It was like some sort of beri-beri, said McGinn. There was no relief from the constant burning, itching and pain. The only temporary relief was to plunge the feet in cold water, but "believe it or not, the water would become very warm". Few, if any of the men affected by the discomfort, lay on their backs for a full night's sleep. They were constantly wracked by the torture of the painful burning feet, and were rubbing, scratching and bathing. The enemy offered no cure. The most vicious guard officer was a Canadian-born Japanese. He would constantly harass the prisoners, and spoke flawless "Canadian". There were many instances of uncalled for abuse from him.

Then began the move from camp to camp. It started on the island of Hong Kong to the mainland of China and back to Hong Kong. Work and more work, all on a diet of rice and boiled seaweed, started the death toll climbing.

As he told stories during this interview in his home, Mr. McGinn's children listened attentively, they said their dad never told them these things, except perhaps for the funny happenings during his incarceration in the enemy camp.

On one occasion while working on the airport, a Japanese soldier approached the 18-year old Canadian prisoner and ordered him to fix his truck. McGinn explained to the guard he knew nothing of the machine, and had never even driven a truck. The guard lost patience and swung a bamboo pole hard across McGinn's mouth. The blow broke his front teeth. He then began fooling around with the truck and it worked "don't know to this day what I did to it." Because of his success, Mr. McGinn was still more unpopular with the guard who believed he lied from the beginning. It was not unusual, he said to get a belt from a frustrated guard, or to be deprived of something that was in actuality already a privation.,BR>

Water was contaminated diphtheria broke out in the camp, and they were "hauling out seven or eight dead a day. One man," said Mr. McGinn, "was more than six feet tall and weighted 220 pounds before he was struck by the camp and the disease. When he died he weighed 50 pounds. He was one of the first to succumb to the water problem." He was John Post of Glassville. "The only thing that saved a lot of us from dying was our morale." He said he and others were determined to keep going to get home and not give in to the enemy. He said a man from Sussex, who was at roll call parade one night said, "to hell with this, I am giving up. I'm not going to fight it any more."

McGinn said the chap went to bed, and in the morning his buddies found him dead.

The troops once slept on concrete floors, but later the enemy collected a lot of steel bunks from the British stores, then supplied "double biscuit" mattresses. Over the months the mattresses soon collected their own inhabitants, bedbugs. To create a diversion, the prisoners would bring the mattresses out into the sun, remove the denizens and place them in a circle made in the sand. Here they would add a goodly number of ants, and bet on the winners. The betting was generally food, because, said Mr. McGinn, that was all we ever thought about... food During the four year imprisonment, the Canadians got one and one-half Red Cross parcels. One was from Canada, and the other was from the US. "There were all sorts of Red Cross parcels in the camp," said McGinn, "but they (the Japanese) would not give them to us."

At no time were the prisoners allowed to call their captors Japs or Japanese. They were to be referred to as Nipponese.

The first inking they got of impending Allied victory was when two gris got close to them while they were walking back to camp. "they told us the Russians had declared war on Japan" McGinn said. He believed the girls were either Russian or German. The same two girls also brought them news that Japan had surrendered. There had been rumors but the Japanese guards were not confirming or saying anything. One night the prisoners were awakened by rockets, fire-crackers, shouting and planes flying overhead. The camp commandant ordered the guards to have the prisoners back in their quarters "as they will be tired in the morning." We knew then it was all over, said Mr. McGinn. Next day there was no work, and the "first thing I remember," said, Mr. McGinn, "was a Canadian navy sailor walking in through the gate of the camp." "That is when I was really sure the war was really done."

"When we went down to the docks," said Mr. McGinn, "I found someone from Fredericton on board the ship..a Canadian ship. He thought I might want a drink and said I could have anything I wanted. I asked for a loaf of bread." The sailor was astonished, but he produced the bread. The excited New Brunswicker, just released from the prison camp said, "I tore it apart, and ate it. It was just like a piece of cake." He said he didn't realize it at the time, but then it came to him " I was dressed only in a Japanese G-string and a pair of Chinese wooden clogs." The trek home was on board the Empress of Australia with a brief stop over in the Philippines. The tired Hong Kong veterans arrived in Victoria, BC almost four full years after they left Canada. Refitted in new uniforms, they headed for home.

When Private McGinn arrived in Fredericton, he was met by his family, a host of friends, a military band, and hundreds of school children. Herby Webber (now proprietor of Herby's Music Store) arranged for a half-day holiday for schools for the home-coming of the Fredericton Hong Kong veteran. It was like a dream, said McGinn of his home coming.

All the pay he had accumulated while a prisoner of war was spent quickly or "given away". He said "If a guy came up to me and asked for 10 bucks, I gave it to him. I somehow lost all value of money and I was still counting in Japanese yen."

Still he is a happy man. Mr McGinn said, "I cant really remember the pains as much but I remember the suffering and the rough deal...somehow it is just a bad dream."

He is now custodian of the Carleton Street Armouries. He is on a 60 percent disability pension. His health is still bad from the long period of malnutrition, his eyesight suffered and his legs are not strong.

(A) Rogers, Staff writer for the Daily Gleaner

Links and Other Resources

There may be more information on this individual available elsewhere on our web sites - please use the search tool found in the upper right corner of this page to view sources.

Related documentation

Our HKVCA Vault (Google Docs) may contain additional information, newspaper clippings, and documents which have been saved for this soldier. To access this information, note the soldier's service number shown at the top of this page, then use the letter prefix to select the corresponding link below. A Google Docs folder list will open in a separate tab. Search for the file identified by the service number to access any additional information we may have acquired.

- Service Number Prefix: A to G

- Service Number Prefix: H to P

- Service Number Prefix: X (Officers)

Facebook has proven to be a valuable resource in the documentation of 'C' Force members. The following link will take you to search results for this soldier based on his regimental number, but they may be incomplete.

Facebook Search Results.

To capture all items for an individual, we recommend visiting our Group: Hong Kong Veterans Tribute of Canada and using the search option there. Note: results may be contained within another related record.

Find a Grave® is a valuable resource that may contain additional information on this 'C' Force member. When you arrive at the site search page, fill in as much detail as you can for best results.

End of Report.

Report generated: 03 Feb 2026.

Additional Notes

(These will not be visible on the printed copy)

- Service numbers for officers ("X") are locally generated for reporting only. During World War II officers were not allocated service numbers until 1945.

- 'C' Force soldiers who died overseas are memorialized in the Books of Remembrance and the Canadian Virtual War Memorial, both sponsored by Veterans Affairs Canada. Please use the search utility at VAC to assist you.

- Some birthdates and deathdates display as follows: 1918-00-00. In general, this indicates that we know the year but not the month or day.

- Our POW camp links along with our References link (near the bottom of the 'C' Force home page) are designed to give you a starting point for your research. There were many camps with many name changes. The best resource for all POW camps in Japan is the Roger Mansell Center for Research site.

- In most cases the rank displayed was the rank held before hostilities. Some veterans were promoted at some point prior to eventual post-war release from the army back in Canada. When notified of these changes we'll update the individual's record.

- Images displayed on the web page are small, but in many cases the actual image is larger. Hover over any image and you will see a popup if a larger version is available. You can also right-click on some images and select the option to view the image separately. Not all images have larger versions. Contact us to confirm whether a large copy of an image in which you are interested exists.

- The 'From' information box at the top of the report represents the enlistment location unless we have obtained updated information pinpointing where the member lived.

- In some cases the References displayed as part of this report generate questions because there is no indication of their meaning. They were inherited with the original database, and currently we do not know what the source is. We hope to solve this problem in future.

- We have done our best to avoid errors and omissions, but if you find any issues with this report, either in accuracy, completeness or layout, please contact us using the link at the top of this page.

- Photos are welcome! If a photo exists for a 'C' Force member that we have not included, or if you have a higher quality copy, please let us know by using the Contact Us link at the top of this page. We will then reply, providing instructions on submitting it.