CHAPTER ONE - My Personal Activity in the Siege of Hong Kong

L.B. Corrigan, Lieutenant, Winnipeg Grenadiers – December, 1941

The introduction to our little war found me stationed at Won Nei Chong Gap, in charge of Mr. McCarthy’s platoon, he being away on a P.T. Course as part of the skeleton manning scheme being practised at the time. In the early hours of December 8, we received a message from Brigade stating that hostilities had commenced at 6:30 and a state of war existed between Britain and the United States and Japan. This rather disturbing bit of news we received with a certain amount of skepticism, since we had been led to believe that Japan would not benefit sufficiently to warrant offensive action, particularly in view of our evident (?) strength, both here and at Singapore. It was with considerable surprise, then, that we were able to hear, about 8:30, the drone of planes and accompanying this, the dull explosions of bursting bombs. The war, for us, had commenced.

The first raid, in which 27 planes took part, lasted approximately an hour and a half and was evidently directed at Kai Tak Airdrome on the Mainland and just about opposite our position. In this first raid, one of the “Facts Concerning The Enemy” which had been fed us was quickly dispelled. We had been informed that the Japs were quite unfamiliar with the finer points of dive bombing. With amazing accuracy, they not only dive-bombed our negligible Air Force, consisting of five antiquated planes, out of existence, but, with the aid of a few well placed “eggs” and some m.g. strafing, succeeded in lending considerable speed and confusion to the evacuation of our barracks at Sham Shui Po by the remainder of the Canadians stationed there. This first touch of war brought with it the initial casualties in the Canadian ranks when two Royal Rifle men were killed in the raid on the barracks. Further raids were experienced during the remainder of the day but since none were directed at the island, we paid them scant attention.

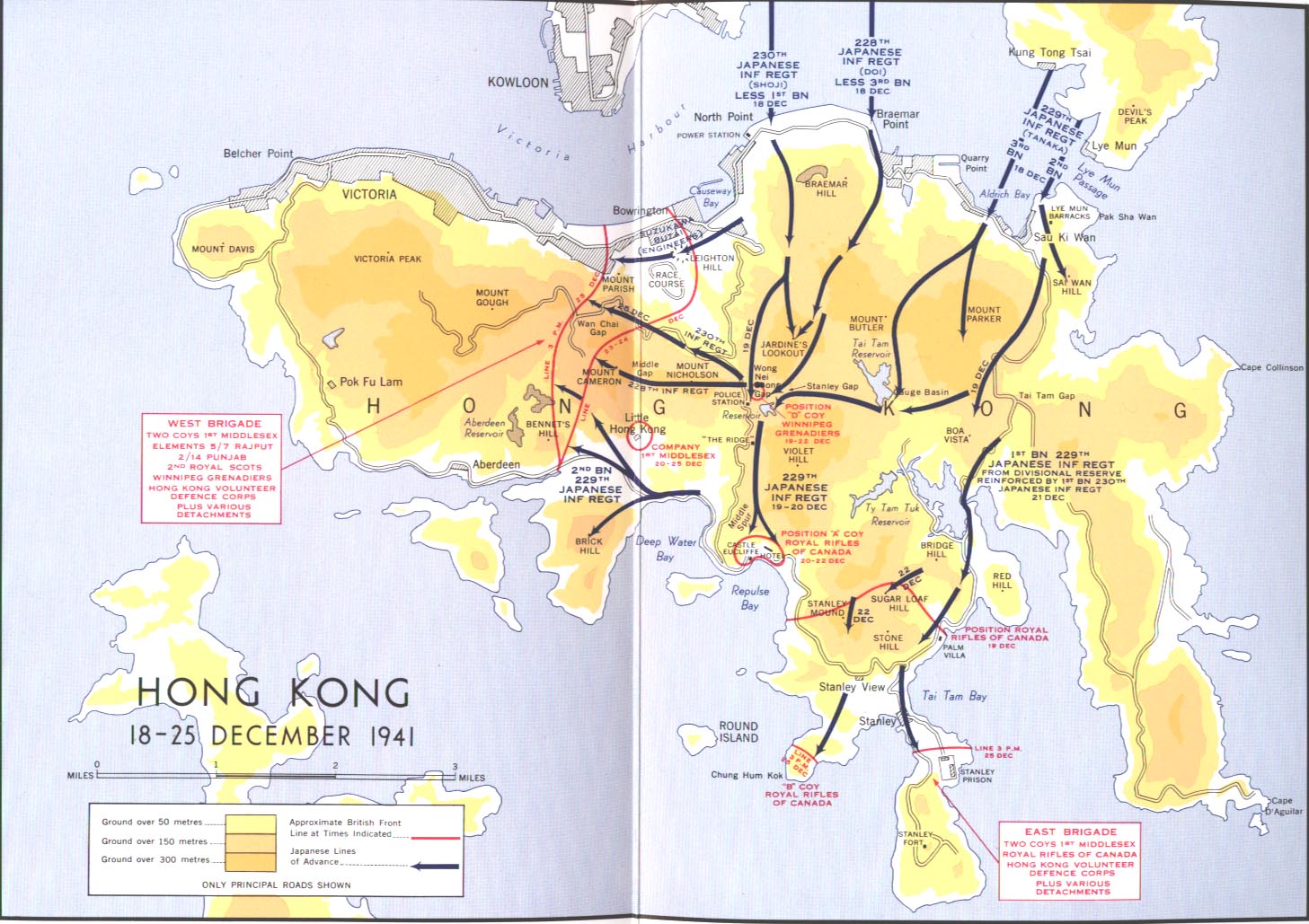

With the arrival on the island of the remainder of the Battalion, it was decided to reform “E” Company as a reserve – which meant that Black, Blackwood, and myself joined Major Baird in a position at Stanley Gap, from where, much to our disgust, we could see none of the bombing of the Mainland. We remained in this position only a day or so – which was quite sufficient – as things were in such a state of turmoil we were unable to secure even guns and ammunition until the second day, not to mention food and blankets. The morning of, I think, the third day, we were moved to Wong Nei Chong to take over from “D” Company, who were to be used in a supporting role to the Limeys on the Mainland. Since Brigade Headquarters was situated at the Gap, our job, for the next day or so, consisted chiefly of manning road blocks and the three road blocks were situated on Jardine’s Peak and afforded a wonderful view of subsequent air raids. After a day or so in this position, we heard the Limeys were to withdraw to the Island for a last stand here. In fact, apparently their whole scheme of action was to have been to hold the enemy for 36 hours to give us a chance to consolidate things. The whole thing was a rather good show in as much as Rajputs, Royal Scots, and Middlesex held a force estimated at 22,000 at bay for three days. The arrival of “D” Company to take up their old position meant a move for us and we presently found ourselves bound for Wan Chai Gap, where our Brigade Headquarters was situated and from where I was destined to operate for the remainder of the war. From this step on, I was caught in such a maze of organization and re-organization and general shifting about that I find it difficult to separate days, platoons, or men: even the men themselves were jockeyed about to such an extent that some of the time they didn’t know what platoon they belonged to. I had, in one day, three separate, newly-formed platoons, so it’s not surprising.

The next, or rather the first active phase of the struggle, for us, came with the landing of the enemy at Lui Mun, on the northeast side of the island, on the evening of December 19th. Due to heavy artillery fire during the day, my platoon had been employed filling sandbags until midnight. We had just settled down to sleep when I was called (at 1:30) and instructed to take up a position at the cross roads below Wong Nei Chong. We had no idea from what direction we might expect the enemy and accordingly we set up our posts to cover all roads and lay quiet to await developments. At approximately 3:30, we received our baptism of fire when the enemy opened up on us with m.g. and mortar and, what we later discovered to be, a light field piece – a weapon whose high bursting power and amazing accuracy earned our deep respect throughout the campaign. This light barrage was repeated at intervals until dawn, evidently intended to be more of nuisance value than anything else, and, aside from keeping us awake, did us no harm. As my orders were to hold fire until actual contact was made, we sat quiet to await the dawn.

Just prior to dawn, intense firing up the valley toward the Gap was heard. I had previously dispatched a runner to try and contact any platoons that might be operating between my position and the Gap, but had received no answer, so we were quite in the dark as to the situation above. A short time later, a company of Rajputs passed through the post, taking the road across the valley, their intention being to encircle the enemy – whom they believed to be occupying Jardine’s Peak. This last bit of news was anything but cheerful, since with proper armament, which they evidently had, the road through the Gap as well as our own position could be controlled from our two P.B.’s located on the peak. Our position at the cross roads continued static and, although we could, after daylight, make out groups of the enemy across the valley, they were beyond our range so we held fire. Around 8:30, a platoon of Limeys passed through, enroute to the Gap, with the news that Brigade Headquarters had fallen and their task was its recapture. This bit of news was something of a shock, but we could do nothing but remain in our position and await developments. Still we saw no action, but from the wounded that commenced to pass through, we learned things were not at all well above. So we were not surprised when about two o’clock we received the order to return at once to Wan Chai to strengthen the line being formed there.

On arrival at Brigade Headquarters (Wan Chai), I found I was included in a party under Major Hodkinson, leaving at once with the object of recapturing the Wong Nei Chong position. The party had been awaiting our arrival so we set out immediately, my platoon in front, with our only carrier supporting us, along Black’s Link, our first objective being the police station at the Gap and P.B. #3. Black’s Link, incidentally, is a narrow road connecting Wan Chai Gap with Wong Nei Chong Gap, and it winds its way roughly in a figure eight or “s” shape around the left flank of Mount Cameron, then the right flank of Mount Nicholson, crossing from one mountain to the other at Middle Gap at a height of approximately half that of the mountains.

With the carrier preceding us, we pushed along unmolested until we reached Middle Gap, where we were spotted and subjected to the fire of their field piece as we crossed the open gap. Fortunately, we were able to reach the shelter of Nicholson with only two or three casualties. The attack plan, originally, was to have operated on a timed basis, in conjunction with a platoon from Repulse Bay side and a “C” Company platoon from Little Hong Kong. A delayed start, however, doomed the time element to failure before it commenced. It fell my lot to have to take my platoon over the summit of Nicholson and try and reach a point behind P.B. #3, situated at the base of the mountain – which meant a fast ascent and descent if I was to be of any value in harassing the rear of the enemy. We commenced our climb at once and for the first 300 yards had a rather hot time of it since we were again strafed by their infernal field piece. The going was pretty heavy as each man carried 250 rounds plus Brens and Bren ammunition and had had little rest and no food since the previous evening. The first stretch of dodging and crawling, coupled with the loads and the steepness of the hill, proved too much for the majority of the platoon so that I was forced to pick four of the hardier chaps and, taking one Bren, with as many ammunition carriers as we could manage, finally reached the summit, well nigh done in.

Upon reaching the summit, we now found ourselves forced with the hazardous part of the undertaking. In order to reach a position giving us proper coverage of our objective, we must descend the mountain, almost to the base, down a long gradual slope, which offered nothing in the way of concealment either from fire or sight, in full view and range of the enemy. Fortunately, by a series of leaps, bounds, and dives, we were able to accomplish this and at once proceeded to set up our gun in a shallow depression, about 300 odd yards to the enemy’s rear. Naturally, our descent had not been made without our having been seen and we came under considerable rifle but no m.g. fire. We held out here for about an hour, during which our gunner did some very fine work with the Bren and found our ammunition supply almost spent – so I decided on effecting a “strategic withdrawal”. While we lay there planning covering fire etc. for our getaway, along came their damned field piece, firing almost point blank, so we cast caution to the wind and made a run and a dive for the far downward slope and safety. Having achieved a quiet spot, we lay doggo for some twenty minutes, then, since darkness would soon be upon us, decided we had better commence our climb homeward.

Our scramble to safety had carried us still further down the mountain on the side away from home, so that we had the alternative of retracing our steps or skirting the hill to the north and climbing down from there. The first course seemed the least healthy of the two so we set out for a new avenue to ascend. Unfortunately, darkness settled down and, though we found the bank almost unclimbable, it was now too late to try our first route, so up we started. To make things even more cosy, a lovely cold rain began to fall rendering the footing very uncertain. The climb, in the condition in which it found us, almost proved too much, and it was only the continual spurring on by one another that enabled us to reach the top. The descent back to the gap was almost as bad and when we finally reached Wan Chai, we were almost done in, it having taken us nearly seven hours for the return journey. Reporting in at Brigade Headquarters at 2:30 a.m., I found our first attack had been successful but the gains were lost to a later counter attack by the enemy.

With the enemy firmly lodged at Wong Nei Chong, our next step was the strengthening of our position at Wan Chai. To this end, it was decided to form a line along the summit of Cameron as a precaution against the probable attacking of Brigade and Base Headquarters to the rear in the gap. The next morning early, I was called in and instructed to set up my platoon in position between the Royal Scots and R.E.’s on the summit so as to be able to control Black’s Link and Middle Gap by fire. After another strenuous climb, I set up my posts, then settled down, hoping arrangements had been made for breakfast. Instead of food, however, after an hour or so in position, a runner brought word that I was to report, at once, to Base Headquarters with my platoon.

Arriving at headquarters, I found I was to take my platoon to a position on the south flank of Cameron, along the aquaduct, to guard against possible enemy movement from that point against Wan Chai. We took our posts along the aquaduct, placing them in positions from where we could command the whole flank, our forward position enabling us, to a degree, to control Middle Gap and some of Black’s Link. Incidentally, this forward post came in for considerable Howitzer fire, so we must have been observed going in. I was able to locate their O.P. and, after sending back a runner with its position, had the pleasure of seeing our artillery blast them from their vantage point. During the afternoon, we witnessed several small actions in the valley below, but as we were hopelessly out of range, could do nothing to help. Late in the afternoon, I sent a runner back for orders and food and at dusk he returned with a jam sandwich per man and orders to stay the night. To make things more interesting, it began to rain and, since we had no ground sheets, we spent a most uncomfortable night huddled together for warmth, there being no cover available. An attack had been planned at dawn and we received word stating that we were in the line of fire of “B” and “C” Companys, so we withdrew, arriving home a very tired, soaked crowd.

About 8:30, I was again called in to headquarters and again ordered to “set up” on Cameron, this time covering the left flank in the defense scheme previously mentioned. We remained in this position for a day and a half, during which time our only excitement was the dodging of mortar bombs – a weapon, by the way, which the enemy had down to a science. On the afternoon of the second day, a runner brought word that I was to report to Base Headquarters alone, so, turning over my platoon to Nugent, started down. On reporting in, I found I was to take a patrol of fifteen men out on Black’s Link and there set up a listening post as close to Middle Gap as I could manage, the Japs, by this time having full control of Nicholson and the gap area.

At dusk we set out and, though nicely silhouetted by burning oil tanks in the city behind us, managed to reach a point within two hundred yards or so from the gap unmolested. Here we set up our post and settled down to await developments. Things remained quiet until about ten o’clock when considerable rifle and m.g. fire broke out to our rear, on Cameron. Being in the field of fire and forced to seek the protection of the wall against the bullets, I sent back another runner to again inform our people of our position. No answer was received, but the firing gradually petered out and we were not bothered further from that quarter. About 2 a.m., heavy artillery fire, which we later learned to be that of our own 9.2’s at Stanley, opened up on the left flank of Cameron about the level of the road over which we had come. This gave us a few bad moments as we felt the enemy must have discovered our presence on the road and intended to search, by fire, the length of the road until they reached us. Fortunately, such apparently was not the case as the fire ceased and we sat tight until dawn.

At sufficient time before daybreak to allow us to withdraw in safety, we started back and, much to our surprise, just before we reached the Gap, found ourselves fired on by a sniper. Failing to sight the sentry at the road junction, I sent the men to billets and started for Base Headquarters to report in and to mention the absence of the road block sentry. Another surprise awaited me there, for I found both Brigade and Base Headquarters shelters empty, lights still lit and evidence of a hasty departure by the inhabitants. Being somewhat non-plussed, I set out to rejoin the men, whom I met about half way from their billets. They were as completely bewildered as I. They had found the ammunition dump blown, and houses and garages that we had used for quarters, set afire – and not a soul in evidence anywhere. Having no idea what might have been happening, but assuming the enemy had broken through, I decided our best move would be a hasty evacuation of the area, the hastier the better.

We had, of course, no inkling as to where the remainder of the Battalion might be located, but the general direction of the “Peak” seemed the logical destination – so with that as our goal we set out. We arrived shortly at Magazine Gap, a point a little less than half-way to the “Peak”, and there contacted a small group of Limeys under a Colonel Field. Colonel Field could give us no news of our people beyond that a party, probably ours, had passed through his position sometime in the night, destination unknown. He knew nothing of the situation at Wan Chai and was quite surprised when I gave what meager details I possessed. This information he immediately phoned into “Command Headquarters”, and, since the enemy had obviously not followed up their advantage in force, asked if I would guide a party, under a Marine Major, back to the Gap to “re-take” the position, as it was vital in the defence scheme of the peak. We set out at once on the return journey and, finding no evidence of the enemy in the Gap, proceeded further to a point on Black’s Link, where we set up a section to deny that approach to the enemy. Returning to the Gap, we were met by a runner who informed us that a company of Royal Scots had taken up positions on the left flank summit of Cameron. Being of no further use to the Major, we again set out for the peak, taking with us a truck loaded with mortar bombs which our Battalion had forgotten or missed in its rush for safety. We arrived at McGough just prior to noon and found the Battalion lying around resting, “etc.”, and in the most horrible state of disorganization. There were actually no sentries or lookouts on duty, and when I mentioned protection to some, it was not even known where m.g.’s could be found for roadblocks, etc. After an hour’s futile search for the Colonel or some senior officer to report in to, I gave up in disgust, dispersed my platoon and had a nap.

To digress a bit, the evacuation of Cameron will probably never be properly explained or accounted for, which, judging by the garbled accounts of it received later, is perhaps for the better. It’s quite evident “Someone had blundered”. In the first place, the position was considered a “key” one in the Island’s defence and quite definite orders to hold it to the last man, last round, etc. had been given. It seems the Nips had first lobbed a few mortar bombs over and in the resulting confusion managed to get in close to our lines in one sector. Evidently, this sector scattered and, for a few minutes, it was impossible to tell friend from foe. To add to the confusion, our artillery, endeavoring to shell Nicholson, dropped a couple of “half-fuses” at the base of Cameron, on our side, and this order came through, although from where, or with what justification, no one seems to know. The enemy must have been as confused as our boys, or suspected a trap, since they made no attempt to follow up their advantage – fortunately.

Having gathered a bit of rest and a bite to eat at McGoughs, things began to look a bit brighter. Around two o’clock, a new re-organization order came through and the next while was spent locating and re-allocating the men to their new platoons. I was given a platoon in a company under Major Baird and told we would form part of a defensive line making a “last stand” before the peak. This, as far as I was concerned, was soon changed by my being made Second in Command of the company, which exalted position I held for almost two hours. Taking the platoon commanders, I placed them in our defensive area then returned to McGough to find that, once again, our plans had been altered and I was now in charge of a platoon under Major Hook - who was to return to Wan Chai with a company and, for the second time, hold that place to the last man, round, etc.

We set out for the Gap at six o’clock that evening, arriving just as darkness began to settle. We found a company of Royal Scots gathered at the Gap, they having been commissioned to hold the left flank summit of Cameron as their part of the scheme. My personal allotment was a small trench system, situated on a spot on the southwest side of the mountain, which afforded a means of denying approach to Wan Chai on the right flank. We settled down here for the night – which proved quite uneventful except for a flurry of sniper’s bullets round midnight, from the top of Cameron – behind us. The powers that be had neglected to mention that the Nips still held the right peak of the mountain. We, rather foolishly I suppose, hoped that since the following day had remained quiet and since it was Christmas Eve, we might experience one of those “mutual” armistices we had heard about. Events were to prove quite the contrary however.

Our Christmas Eve started out in the traditional “not even a mouse” fashion, and we sat around discussing the folks at home and wondering about preparations being made there for Christmas. About 10:30, I was called in to Company Headquarters by phone and instructed to take out a patrol to ascertain if there was any enemy activity in the area, and to report back as soon as possible. Returning to the trench, I detailed six men to follow and set out. There was no moon but it was one of those clear, starry nights when visibility is fairly good.

Since our position crowned the spur, the descent was made along a path that topped a long ridge to the base. At a distance of fifty or sixty yards from the trench I stopped, thinking I could detect movements in the grass. We listened for a few moments and, hearing nothing further but satisfied that I had not been mistaken, I sent a runner back to warn the boys to be on the alert. We had proceeded only another thirty yards or so when I was positive there were movements in the grass on both sides of us. Listening carefully we found this to be so and, since we were quite vulnerable due to the ridge we were on, I decided the wisest thing to do would be a return to the trench, before we were cut off. Ordering the men about we started back, with myself in rear. We had progressed only a few feet when I saw movements to our right and, dropping to one knee, I sighted about twelve of the enemy proceeding toward the trench, in single file and almost parallel to us, at a distance of approximately thirty-some feet. Shouting their position to the boys, I brought up my rifle (which I had picked up in the trench sans bayonet and sling) and taking aim, squeezed the trigger, only to find I had neglected to leave a round in the chamber. Our opponents, having been seen, elected to charge with bayonets, so I let loose a grenade, holding it as long as I dared due to the close quarters, then tossed it underhand into their midst. Fortunately for us, the grenade apparently just lobbed over their heads and exploded waist high directly behind one poor chap whom, I learned from our boys later, it literally blew into the lap of one of our chaps. That’s probably all that saved us the task of picking mills fragments from our persons.

The events of the succeeding minutes remain somewhat disjointed, due to the rapidity with which things happened and the loss of my own sense of time. However, having checked with other members of the patrol, I believe the continuity as laid down is correct. On releasing the grenade, I charged my rifle and shot one chap through the chest, then, with the enemy upon us and having no bayonet, I proceeded to lay about me with clubbed rifle in the most approved story book manner. In the general melee, I succeeded in knocking the rifle and bayonet from one chap’s grasp and picking it up ran another through the side or middle. Unfortunately, I found I couldn’t withdraw and, in an effort to extricate my weapon, tossed my small friend, in the manner of handling hay, over my shoulder and to the rear. Whether the bayonet stayed with him or not I couldn’t say, but I seemed quite suddenly to be without a weapon. At this unhappy moment, one of them came at me with a sword, and, having nothing with which to fend the blow, I had no choice but to rush in and grab the blade as it descended. Gripping the blade with my right hand, with my left I encircled his head and shoulders and thus deadlocked, we scuffled around until one of us lost his footing and we rolled down a gentle slope of about ten feet, to one side of the path.

The arrival at the bottom found us still locked together and since each was wary of loosening his grip lest the other get an advantage, it looked like an all-night session. Apparently similar thoughts were running through my friends’ head for he suddenly gave vent to four or five cries that sounded like ‘kill, kill!”. Those were my sentiments too but I didn’t like the publicity he was bound to get. Looking about to see what results his cries might bring, I saw one of his pals, evidently intent on rendering assistance, about to descend from the path and to our right. This didn’t enhance the situation from my point of view but it did give me added incentive to have things over in a hurry. In the midst of my renewed efforts it dawned on me that I still carried my pistol, until now unused. By considerable frenzied scrambling, due to my having to hold my opponent close while doing so, I finally reached my holster only to find it empty. The cord or lanyard, however, was still about my neck and I followed it down until I reached the weapon. Another problem here presented itself. Due to the wound in my hand, I found myself unable to squeeze the trigger with my index finger – business of shifting from first to second – and – to spare the more sordid details, I finally managed to dispose of him.

Having expected these last few moments, to be run through from behind, one can imagine the feeling of relief on jumping to my feet to find myself quite alone – both friends and enemies having disappeared. Grasping my late adversary’s sword, I made to reclimb the bank but found, after a step or two, that I was too exhausted to even crawl – so I lay down to regain my strength. I tried to shout to the trench for someone to give me a hand, but I evidently went unheard. How long I lay there is difficult to say but while in the prone position, I again detected the swishing of the grass, denoting enemy movement, I crawled to a point beside the path and there the sound was unmistakable. The enemy, as near as I could judge, was approaching the trench from the front and right flank. Since their position to a degree, cut off my route back, I again shouted to the trench, warning them of the impending attack and how to prepare against it. By way of answer, I was rewarded by the firing of four flares that seemed to all find an attraction in my hitherto inconspicuous position, so that I was forced to lay quite flat, hoping that my shouting and the flares would not bring a “rubber-outer” my way. After a few moments that seemed as hours, I decided I had nothing to lose by a run for the post so I gathered myself to run the gauntlet. My run, which was more of a stagger, had carried me more than half way before I encountered any signs of the enemy, but at this point I again heard movements so I dropped to one knee for a look-see. On my left, I could just make out one chap in a standing position and, since I now carried my pistol in my left hand, I blazed away at him. (I couldn’t even hit a barn with my right!) Not caring to await further developments, I again commenced to run the remaining distance, at the end of which I dove, quite ungracefully, into the trench. Again I had a shock coming. I found myself to be the sole occupant of our post!

This last jolt spurred me sufficiently physically so that I was able to reach the path to Company Headquarters without wasting a great deal of time. Just before reaching the first of the houses, I found one group of men, a Corporal and section, who, when questioned as to why the men had left the trench, declared that when the main body had pulled out, having believed me to have been killed, he had been willing to stay, but felt he could do little with eight men and so had gone along. Ordering him to return at once, I went a short distance further to find the remainder of the men on the road near Company Headquarters. Ordering them to return at once to the trench, after several slighting remarks regarding their character and antecedents, I had my hand given a rough dressing, then returned to the post to prepare for the enemy.

On returning to the position, I had no trouble getting every thing ship-shape as the men still felt somewhat sheepish over their earlier performance. As it turned out, the enemy apparently had no idea that they could have walked in and taken over our position without any opposition but instead, in their methodical way, they went ahead with their attack plan, making sure each and every man was in his appointed place. We had waited perhaps a half hour or more when we heard a shout to out left rear, answered by another to the right and behind us. This evidently was the signal for the attack to commence, for, with a great surge of yells, they bore down on us from three sides while from the fourth, the sides being too steep to climb, they kept up a heavy fire with rifles.

The next hour was quite hectic as anything one could possibly wish to go through, and it’s really impossible to describe feelings or actions accurately. Since my job was to supervise and encourage the men as well as direct their fire, etc., I found myself seeing things through the eyes of a spectator rather than a participant, although I did lob a few grenades and fire my rifle occasionally. Even with this advantage, however, all that comes to mind is the terrific blend of noise, gun-flashes, and the smell of powder. I had cautioned the men to hold fire until actual sight of the enemy, then grenades were to be used in conjunction with the Brens. I believe this plan had considerable to do with the ultimate failure of the enemy attack, as their first formation was so badly disrupted that there was very little actual hand-to–hand work after our first grenade barrage. Our mills grenades, by the way, were so far ahead of those of the enemy that there was no comparison. We were fortunate too in having more than our quota of Brens for the job, having five for approximately thirty men and with four men per Bren loading magazines, we presented an almost impenetrable wall of fire. Again and again the officer endeavored to rally his men for a close-in fight, but to advance through that hail of lead would have been an impossibility. For the most part, the enemy contented themselves with getting as close as they dared, tossing a grenade or two.

After what seemed ages, the attack finally petered out and I was given a chance to reckon the damage done. Making a general check I found we had been most fortunate, for, aside from slight shrapnel wounds, we had only one man killed. Our “Sigs” had taken a bullet through the neck. Since there still remained more than two hours till dawn, we felt the enemy might make a further attempt and accordingly set to work to get things ship-shape such as gun cleaning, etc. As it turned out, such was the case, but it was only a very brief repetition of the first, except that it lacked the savage persistency of the earlier attempt. Evidently, the enemy, being human, had no taste for lead and we weren’t given a good work out. (Thank Heaven.) After the last episode in which we had no serious casualties, we settled down to await the dawn which, fortunately was not far off.

A general check-up at daybreak revealed a shortage of ammunition and grenades, so contacted Major Hook by phone, reported the evening tiff, and asked him to send ammunition, rations, and rum (we hoped). I waited until around 9 o’clock and still no supplies, so since communication had broken down, sent in a runner. With no reply by 9:30, I sent another and at 11:00 still another, all of whom failed to return. Since Company Headquarters was only a matter of a ten minute walk and everything was quiet, I decided to go in myself and see what was what. Arriving at Company Headquarters, I was met by Major Hook who promised the boys would be looked after at once and who insisted I go with him to Base Headquarters to have my hand properly dressed. Since the boys were a little on edge after the previous night’s business, I asked that he send a senior NCO with the supplies to look after things until my return. Assuring me this would be taken care of, we set off for Base Headquarters and I took with me the sword of the previous evening’s episode - turning it over to Harper to hide for me. I arrived at Base Headquarters and found the Colonel engrossed in a counter attack plan to relieve a platoon, surrounded by the enemy the night previous, on Bennett’s Hill. After considerable argument, I was able to convince him that with a pair of Vicker’s guns, I could quite easily work on the enemy’s rear from my trench as we were a trifle out-ranged with the Brens. With his promise that the Vickers would be up by two o’clock, I took my leave.

I had just stepped out the door of the shelter when a man rushed up to say my men of the trench had gone through his road block on the run. Picking up a bicycle, I hurriedly made my way to the road block. Arriving there, I found everything quiet and the sentries completely in the dark as to the reason for sudden departure of my men or their present whereabouts. Since our position was quite important strategically, in the proposed counter attack as well as the Wan Chai defence, my first consideration was its re-occupation. Having no idea what the situation might involve, I called for two volunteers to man a Bren and accompany me back to the trench. Sergeant Porter with three men and two Brens stepped forward, so off we started, Sergeant-Major McFadyen promising to gather a few more men at once and follow us in.

On the path, between the block and the trench, we were subjected to a bit of sniping from the valley below but no casualties resulted. On nearing the trench, a Bren man and myself edged forward under cover of a slight ridge to a point where we could observe and bring fire to bear and, on arrival there, were quite surprised to find the trench apparently un-occupied. Calling up the remainder to give us covering fire, we dashed forward and finding no opposition set up our gun then signaled the all-clear to the rest. Investigation of the trench disclosed a mortar bomb had dropped on one of the gun positions, killing the gunner and evidently the remainder had become panic-stricken and evacuated in a hurry, leaving Brens, rifles and equipment where they lay.

We spotted the enemy in fairly large numbers at the base of our spur and, since they seemed to have established some sort of breast-work in the woods, we decided we might just as well give them something to worry about from our angle. Although the range was a trifle long for really accurate shooting, we nevertheless peppered both that position and the enemy’s rear on Bennett’s Hill, causing considerable agitation in both spots. We soon found that two could play that game when they were able to bring their m.g.’s to bear on us, and things settled down to a sniper’s game in which we had, due to our position, quite some advantage. Around three o’clock we heard firing to our rear, in the approximate locality of Base Headquarters and, since our Vickers party and re-enforcements had failed to appear, I decided we had better pull out and investigate lest we be cut off from the rear. Our evacuation was a bit trickier than coming in as we came under heavy sniper fire, but managed to reach the road-block with only two casualties, neither of them very serious. Passing through the road-block, which we found deserted, we were further subjected to LMG fire from Cameron so I decided we’d better make for Base Headquarters at once. Arriving there I was again to experience that “when a fellow needs a friend” feeling for, once more – without our having been warned, we found Base Headquarters deserted and the Battalion headed for safer climes.

With no inkling of what might have caused the withdrawal, other than the fact that we were being shelled damned heavily and subjected to a bit of m.g. fire, we decided we should once again make for the peak. Gathering together all the workable Brens we could find and numerous grenades – quantities of both were lying all over the place – we hid what we couldn’t carry and set out. Since the upper and shorter road beyond Magazine Gap seemed to be taking a terrific pounding, we took the lower road, which meant that we would be faced with a much stiffer climb at the end of our journey. After an hour or so of terrific exertion, due to our heavy loads, we finally arrived at the peak, there to receive our greatest surprise – we had hoisted the white flag.

As can well be imagined, news of that nature, coming to men keyed up to battle pitch for days and with scant food and rest, can be a very great shock and the manner in which some received it was most pathetic. Pent-up emotions were given further impetus by the looting of stores of liquor and cigarettes and the combination of circumstances seemed to crumble the thin veneer of civilization within which men’s animal nature seems to lurk. Such an exposition was most revolting and may I never witness again an army in defeat. Surely, nothing portrays more vividly the frustration, lost hope, and extreme selfishness of the individual.

And so – in a little more than two weeks, my usefulness, if any, as a soldier whose military education had cost the government thousands of dollars, was finished. Perhaps we all might have done better under different circumstances, but I feel that most of us did our best here, and particularly am I proud of the fact that the replacement officers were at all times in the thick of things as can be seen from the casualty list, nor did I hear of any instance of the new chaps “cracking”. So – all in all – though short but sweet, we’re through and, when results are viewed away from the thrill of battle, we must admit that perhaps Sherman was right